No batteries, no circuitry or electrical elements, no motor – just impeccably tuned mechanical parts, working harmoniously to produce a controlled result. This description could fit a number of objects: bicycles, musical instruments and traditional watches spring to mind. Cameras, however, do not.

Since the 1980s, the consumer photography industry has been obsessed with electronic features. Digital cameras, obviously electrical, dominate the market today, but even in the latter days of film, motor winders, autofocus, electronic zooms and automatic exposure were aggressively marketed as tools to make photography ‘easier’. This obscured the fact that, at its heart, photography is a mechanical process. All that is required to take a picture is a light-sensitive material (either film or a digital sensor) and a shutter to allow light to hit that material.

Little revolution

Prior to 1913, cameras were huge, bulky affairs with curtains and stands, exposing large, fragile glass plates one at a time. In that year, however, a man named Oskar Barnack changed the course of history with a humble side project.

Barnack worked for Ernst Leitz Optische Werke in Wetzlar, Germany, in charge of microscope research. His knowledge of optical glass led to a natural interest in cameras, and he was known to enjoy landscape photography. What he did not enjoy was carrying the enormous, heavy gear the hobby required at the time, particularly given he was an asthmatic. So, he focused his energies on creating a smaller, more portable alternative.

At its heart, photography is a mechanical process. All that is required is a light-sensitive material and a shutter

At the time, 35mm film was in regular use for motion picture production, but was only used in a handful of still cameras, none of which were capable of decent quality results. Using his knowledge of high-quality glass optics, Barnack developed a 35mm camera small enough to be handheld or worn around the neck, with a lens that could rival the large-format cameras of the time. He also changed the standard aspect ratio of the film, so that, instead of the 18 x 24mm vertical image standard in movies at the time, his camera used a larger 24 x 36mm horizontal frame, which further improved image quality.

The First World War delayed further development, but eventually, in 1924, Barnack convinced his employer to produce his invention for public sale. The following year, the Leica (a truncation of ‘Leitz camera’) went on sale, proving an instant hit and making high-quality photography a truly portable thing. From holiday snaps to journalism, the impact was far reaching.

Heroes of the past

Henri Cartier-Bresson made an art form of candid urban photography using a Leica. Robert Capa showed the world the moment a Spanish Civil War soldier lost his life in 1936 using a Leica. In 1960, Alberto Korda took the iconic, now ubiquitous portrait of Che Guevara using a Leica. Josef Koudelka captured the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968 using a Leica. Nick Ut distilled the horrors of war with his Napalm Girl image in 1972 using a Leica. Queen Elizabeth II photographed Prince Phillip at the 1982 Windsor Horse Show using a Leica. In 2000, Arthur Miller’s wife photographed Fidel Castro during dinner using the only camera Castro would allow at the table: a Leica. The camera, in its various models, has accompanied and documented much of modern history as we know it, and it owes this status to its mechanical simplicity, quality and reliability.

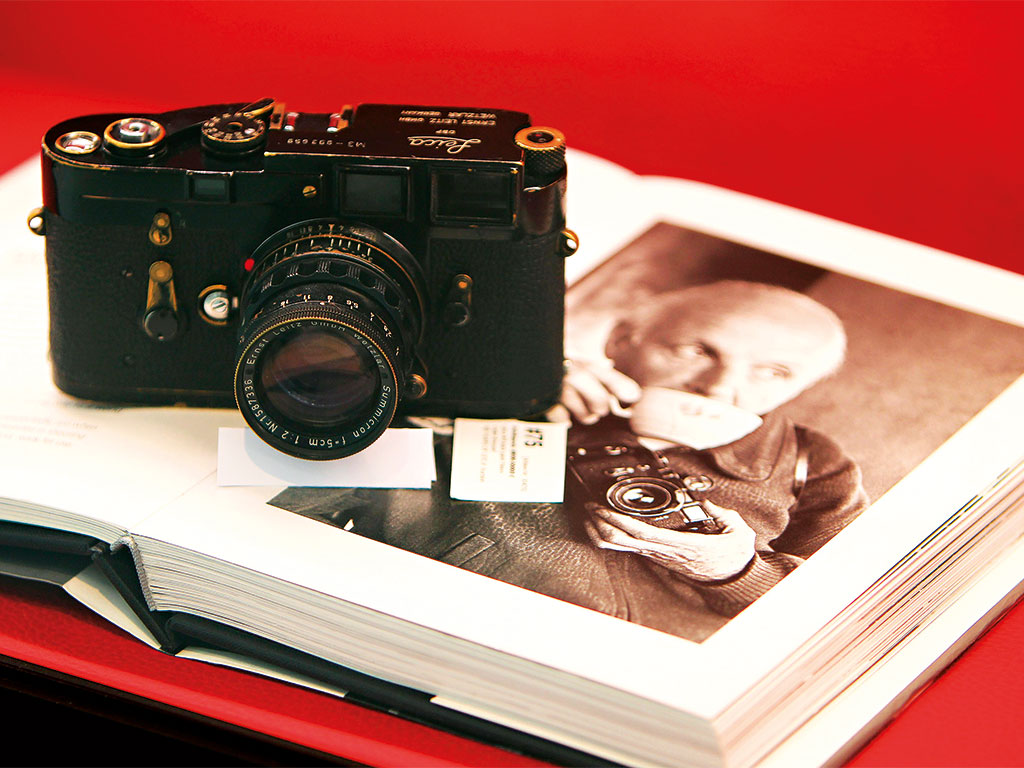

So what is the modern appeal of Leica cameras? In this world of plastic digital models, reliant on technology that becomes outdated every few years, Leicas offer something different: an antidote to gear-focused consumerism that distracts from the artistic process. The Leica M3, which many still regard as the pinnacle of the company’s efforts, features just two controllable elements: the aperture of the lens (i.e. how much light it lets in) and the shutter speed (i.e. how long it allows light in). This means there’s nothing in the way of the photographer and their creative vision – nothing to go wrong, once experience takes human error out of the equation.

To this day, Leica cameras are handmade to incredibly exacting standards by expert technicians

For this to work, the camera must be built from the highest quality materials to a level of precision that defies production line construction. To this day, Leica cameras are handmade to incredibly exacting standards by expert technicians. This is reflected in the price, with new models costing upwards of €5,000. It is also why they have become collector’s items, prized for their intricacy and historical importance.

Inevitably, there are collectors who buy Leica cameras purely as investments, to sit on a shelf. The company itself has clocked on to this, producing a range of limited editions throughout the years. These are sold for extortionate prices to appreciate in a display case, and then sold on for even more extortionate prices, often without ever having tasted a single roll of film. Perhaps the nadir of this sad trend was the Leica M-P Correspondent: a brand new camera that had been carefully pre-rubbed to look worn, revealing the brass beneath the exterior paintwork, which is normally a proud sign of a life of heavy use. Of course, the same effect can be achieved for a fraction of the price by buying a second-hand model and simply using it over time.

Thankfully, most aficionados appreciate the dual collectability and usability of a camera that is built like a tank, using solid metal parts. “If you are concerned about losing value on a camera, then maybe you are buying it for the wrong reasons”, said Bellamy Hunt, a Leica expert who specialises in sourcing used models for his clients. “Even the most avid collectors I know put a roll of film through their most precious cameras from time to time.”

Photography guru Ken Rockwell concurred, writing on his blog: “A camera has no value if it’s not used; you can’t take its resale value to heaven, but your images will last forever and make you immortal when you shoot it.” With a Leica, this is easy, as Rockwell explained: “With a top-notch camera like a Leica, it will stay like new for decades and decades… the reason Leicas earned their reputation is precisely because of the amount of use you can give them, while still looking and working flawlessly.”

Me no Leica

Like many of the great names of the age of film cameras, Leica initially resisted the lure of digital photography when it came to prominence in the early 2000s. The company did release a few basic models, usually based on existing cameras from other companies, which were merely tweaked and then sold for higher prices. After all, the thinking went, Leica cameras were regarded as the world’s finest, and were the go-to choice for photojournalists worldwide. What’s more, digital sensors at the time were far inferior to film in terms of resolution, colour definition, tonality and dynamic range. In any case, as the Financial Times noted in an interview with Chairman Andreas Kaufmann, “there were difficulties marrying Leica’s core M range with digital electronics”. Like Kodak, that other great stalwart of the film era, Leica’s fortunes took an abrupt turn for the worse. Their cameras, already low volume sellers due to their price and durability, almost stopped selling altogether and, by 2004, one of Europe’s last remaining camera manufacturers was on the brink of bankruptcy. It was at that time that Kaufmann stepped in.

Leica is now a luxury lifestyle brand, squarely aimed at those for whom money is no object

A teacher by profession, Kaufmann was also a member of the family that owned Austria’s largest paper mill, and commanded significant wealth. “I led a double life, one half working as a teacher, the other looking at real estate investments in the US”, he told the Financial Times. Tiring of the pressures of this life, Kaufmann wanted a new challenge. “I felt the need to do something different – something on my own to use some of the money.” His decision was to invest in the struggling icon.

Kaufmann bought the entirety of Leica’s shares, taking on an executive role in the process. He guided the company to invest heavily in research and development, and pushed the development of a digital model that stayed true to Leica’s principles. Thus, in 2006, the Leica M8 was born. A deliberate continuation of the iconic M series, the camera was compatible with all of Leica’s existing M lenses, so entered into a line that could trace its lineage directly back to Barnack’s original creation.

Robust, well-built and blessed with the same luxurious user experience that had come to define Leica, the M8 and its successors saved the company. Between 2011 and 2012, Leica’s revenue doubled, from €150m to €300m. Jobs were saved, a legacy was rescued from a sad end, and production and servicing of all models – including film models – could continue. Undoubtedly, it was a good result.

All the same, it is hard to resist the conclusion something has been lost. Leica can’t be blamed for fighting to survive – and survive it has, with private equity firm Blackstone now owning 45 percent, and sales strong. But the combination of build quality designed to last several generations (given occasional servicing) with digital technology that is essentially finite doesn’t add up. Indeed, Leica’s digital cameras – unlike their film predecessors – cannot be said to be ambitious purchases for aspiring photographers willing to invest once in a pricey model and then care for it for a lifetime. Leica is now a luxury lifestyle brand, squarely aimed at those for whom money is no object, while budding photojournalists and artists look elsewhere.

History is constantly being written, and Leica will sadly no longer be its companion. But the company’s link with the 20th century, when so much of the world we know was shaped, will stand the test of time.