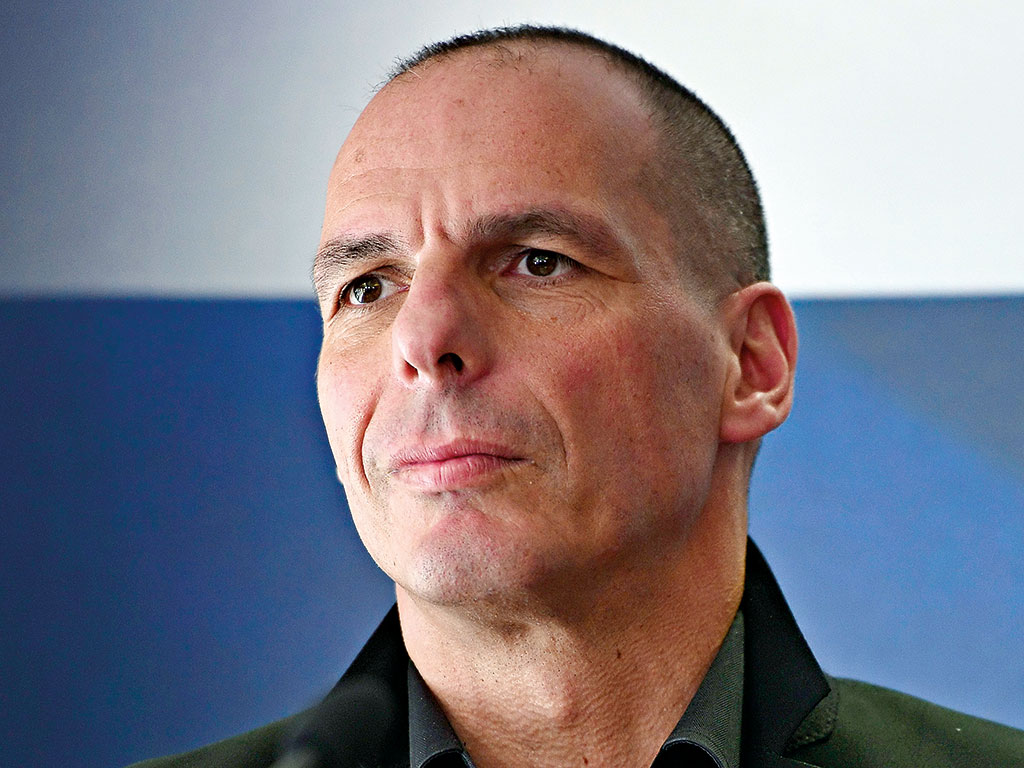

On July 5 2015, after months of tense negotiations between Greek government officials and European leaders, the Greek population voted in a historic referendum. Asked whether or not to accept certain austerity conditions and unlock bailout funds, the people of Greece overwhelmingly voted no. This, at the time, was lauded as a big victory for the Syriza government, which called for the referendum in the first place and urged a ‘no’ vote. However, one man in the government – though pleased with the outcome – reacted in an unexpected way. The morning after the result was announced, Yanis Varoufakis announced his resignation as Minister of Finance.

Upon entering government, Varoufakis immediately became a media sensation, riding his motorcycle to meetings and appearing next to European leaders sporting an unbuttoned shirt and boots. As Suzanne Moore wrote in The Guardian: “Clearly, in the world of Eurocracy, to not wear a tie is radical. Or rude. Or both. Sometimes he wore a leather jacket. Or a Barbour, or a shirt that was perhaps a little bit too tight. He signalled simply that he was not another ‘suit’, and made the rest of them look stuffy, uptight and clonish.”

Varoufakis seemed to revel in the role he had created for himself, happy in his status as the arch-enemy of Brussels and Berlin

In a post on his personal blog, the former minister hailed the referendum result as “a unique moment when a small European nation rose up against debt-bondage”, urging that “the splendid ‘no’ vote” be used by the Syriza-led government to secure “an agreement that involves debt restructuring, less austerity, redistribution in favour of the needy, and real reforms.”

He went on, however, to claim that this would best be achieved without him in the role of Minister of Finance, adding that he had been made aware that his absence from any further negotiations would strengthen the country’s bargaining position. So, in the hope of Greece securing the best possible outcome from future talks, he, along with Prime Minister Alexis Tsapris, felt it best for him to resign immediately. “We of the left know how to act collectively, with no care for the privileges of office”, he said.

Activist to academic

Before irking the most powerful men and women in Europe, Varoufakis was a relatively obscure economist. Born to a politically active family, his father was a communist veteran of Greece’s civil war, and later an activist in the centre-left Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK). At a young age, Varoufakis helped set up the youth group of PASOK, and as a teenager he developed an interest in the Irish Republican Army, supporting the Troops Out Movement, which advocated an end to British military presence in Northern Ireland.

After gaining a PhD from the University of Essex, Varoufakis went on to hold a number of teaching positions at universities around the world, before returning to his native Greece and taking up a position at the University of Athens. In the early 2000s, he made his first foray into politics, acting as advisor to George Papandreou’s PASOK government, ironically the same government that created much of the mess Varoufakis would later take on the role of trying to fix.

In late 2011, he was headhunted by Gabe Newell, CEO of Valve Software, where they were having trouble scaling up virtual economies on their platforms. This led to him being hired in 2012 as the economist-in-residence at Valve, where he researched for Steam and its virtual economy, which he detailed in a blog.

Emerging critic

Speaking to The New Economy while at Valve in 2013, Varoufakis’ disdain for conventional economics and its practitioners, for which he would later become world famous, was already clear: “After the crash of 2008, we have no excuse to continue living in hope that economic models can be as useful to the social theorist as mathematical physics is in helping explain the universe. Economics resembles a religion with meaningless equations and fruitless statistical models.”

He would later express his view on the current state of economics further in his 2013 book The Global Minotaur: America, the True Origins of the Financial Crisis and the Future of the World Economy. Prior to this, he had penned a number of other books, but the larger part of his work was academic, concerning the finer details of game theory economics, which had little readership outside of academic circles.

The Global Minotaur, which takes a long view of how the 2008 economic crisis developed over the centuries, takes aim at US hegemony and economic policies, and was printed by Zed Books, a publisher known for its left-wing output. This helped propel Varoufakis to the forefront of left-wing thinking in Europe. The premise of the book is that the US economy is reliant upon the primacy of the global economic dollar surplus. While the US enjoyed the position of the global surplus economy since becoming a debtor nation in the 1970s, a huge part of the world’s capital flows were being sucked in, leading to financialisation and the creation of various Wall Street bubbles.

Haters will hate

Although he never actually joined Syriza, he became one of the most familiar faces of the government it formed. In his first few days in government, the British press was ablaze with intrigue about the man meeting top UK cabinet ministers. Though generally calm and self-effacing in the spotlight, he did attract criticism for posing with his wife in a luxurious photoshoot in a French magazine – something he later regretted.

His biggest critics, however, were those he was tasked to negotiate with. Sticking to his guns over his core belief in the need for Greek debt relief, various finance ministers and other European leaders openly expressed their disdain for the motorbike-riding renegade.

Varoufakis seemed to revel in the role he had created for himself, happy in his status as the arch-enemy of Brussels and Berlin. He often took to Twitter to voice his disdain for European officials; after one conference he not-so-subtly quoted Franklin Roosevelt, saying: “They are unanimous in their hatred of me…and I welcome their hatred.” His relationship with the German Finance Minister was particularly rocky, saying once: “We didn’t even agree to disagree.” In his resignation blog post, he boasted that he would “wear the creditors’ loathing with pride”. He maintained his maverick status to the end, giving his resignation conference in casual attire, later to be photographed in a bar drinking beer with friends.

Despite the shortness of his time in power, his personality, politics and charisma mean he will be remembered for as long as the crisis in Greece continues. With a CV consisting of various academic posts, employment by one of the largest gaming companies in the world, and a starring role in attempting to remedy the biggest crisis the EU has ever faced, Varoufakis is sure to have plenty of options for his next move. Few, however, would bet on a predictable turn.