As 22-year-old Sophia Amoruso sat idly by the security desk of a San Francisco art academy, her mind came to rest on an interesting conclusion – that she, like many others her age, could wield social media to shift second-hand clothes online, and for a tidy profit. Where once she used Amazon to sell stolen books, Amoruso used eBay, together with a lively social media presence, to create NastyGal. What began as a vintage outlet soon grew into a multimillion-dollar enterprise and the fastest-growing online retailer in the US.

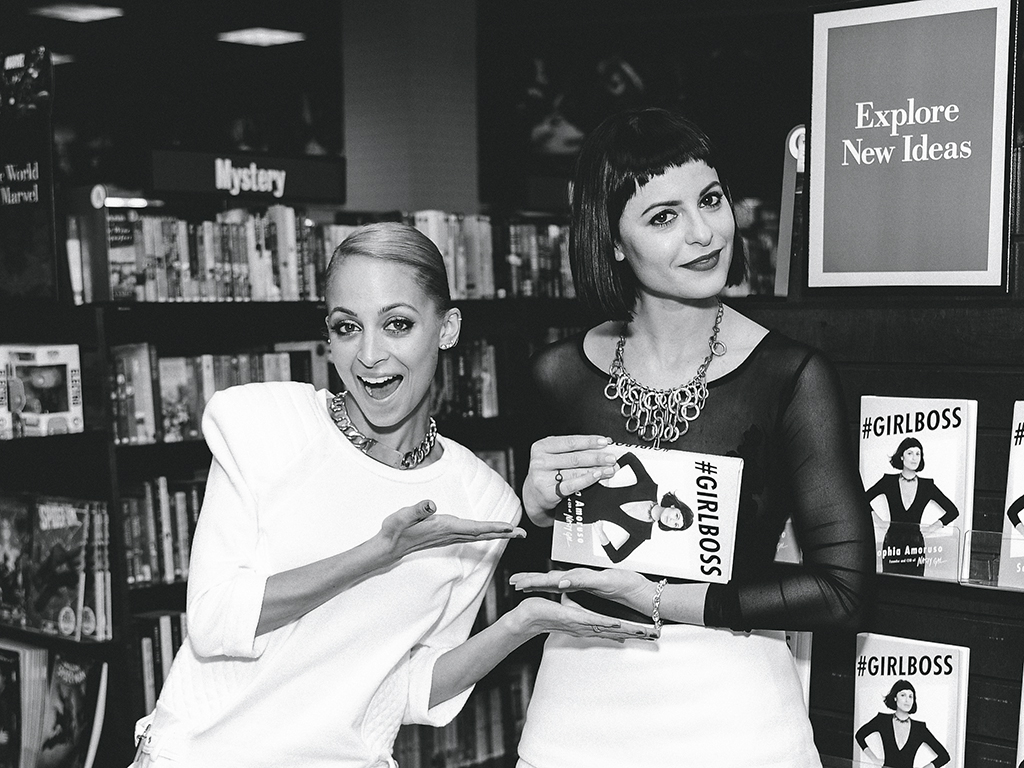

With $100m-plus in revenue and an impressive reputation to boot, NastyGal has fast become the envy of established – and stagnant – high street giants. In the early days, Amoruso picked up a Chanel jacket for just $8 at a Salvation Army store, only to sell it later for over $1,000, and while the business has changed immeasurably since, this entrepreneurial spirit remains the same. The NastyGal founder and, until recently, CEO racked up yet another feat last year when she launched the #GirlBoss foundation to coincide with her book of the same name, in which she offered her typically maverick take on business to aspiring millennials.

In an economy dogged by low inflation and sub-par growth, allowing entrepreneurs to flourish is essential to creating employment opportunities and boosting business confidence

Admittedly, the foundation offers only modest grants to ‘female creatives’ (in the $500 to $15,000 range) but what’s more important is that, in a world where only five of the FTSE 100 companies are headed by women, the scheme’s founder and figurehead serves as an example of how female entrepreneurs might smash that glass ceiling and make a successful business in a male-dominated sector.

“Female entrepreneurship is a big topic and there are many different factors that impact the number of women setting up and running successful businesses across Europe”, says Maggie Berry, Executive Director for Europe at WEConnect International. “The most commonly cited obstacles are lack of access to funding and the lack of role models, but there are many more nuanced factors as well, including the types of businesses women set up, the sectors they work in and the overall number of women setting up businesses compared to men.”

A deep-rooted issue

The issue is one that has been addressed time and again by a continent that is crying out for fresh employment opportunities, yet figures show Europe’s entrepreneurship sector is not as inclusive as it might seem. One study carried out by the European Commission in September found that, as of 2012, there were roughly 40.6 million active entrepreneurs in a sample of 37 European countries, including all 28 EU member states. Chief among the findings was that only 29 percent, or 11.6 million, were women, and that even Liechtenstein, the country with the highest number of women entrepreneurs, was 57 percent male-orientated. While the survey went on to note that there are more women running a business today than there probably ever have been, there is a great deal to do yet before Europe is seen as an accommodating climate for female entrepreneurs.

In an economy dogged by low inflation and sub-par growth, allowing entrepreneurs to flourish is essential to creating employment opportunities and boosting business confidence. Entrepreneurship is seen largely as a catalyst for growth and EU findings show the sector creates four million jobs annually for member states. Unfortunately, the sector is also seen as a male-dominated one, and justifiably so. Whereas the male-female disparity in the labour market is nearing parity, entrepreneurship is quite another story. It is a key driver of growth, innovation, employment and social integration, so, without addressing the gender inequality issue, the talent shortage will persist and the economic malaise will continue.

Only by identifying exclusionary policies and imbalanced institutional structures can women compete on a level footing with men. By implementing systems whereby women are given license to pursue entrepreneurial projects as they wish, the region will be better equipped to fight the issue. “Europe must build on its small businesses. Supporting women entrepreneurs is essential to stimulate growth since the entrepreneurial potential of women has not yet been fully exploited”, according to Antonio Tajani, former European Commissioner for Industry and Entrepreneurship.

By setting up dedicated support groups and taking pains to source better data on which to base policy decisions, the EU has played an important role in lifting the number of female entrepreneurs by three percent in the period from 2008 to the present day. “There are, and have been, many programmes supporting female entrepreneurship across Europe”, says Berry. “I believe there is still a lot more to be done in this space – taking the UK as one example, less than 20 percent of business owners are female but women make up 50 percent of the working population, so women are missing out on economic wealth. SMEs represent 99 percent of businesses in the EU and we’re keen to see more women succeeding and achieving in business ownership.” More steps must be taken by both public and private institutions to support entrepreneurs and, in doing so, bring more female-run enterprises into the mix.

Granted a lifeline

One key area where government and support groups are making progress is in grant funding, where, much as is the case with the #GirlBoss foundation, women are being given financial license to pursue their chosen business ventures. RBS’s Inspiring Women in Enterprise programme is proof that there exists a willingness in the financial community and beyond to address the gender imbalance. After the release of a report, entitled Women in Enterprise: A Different Perspective, the bank found the rate of self-employment among women has been half of that among men since the 1970s, and went on to note that, while women made up 48 percent of the working population, only 26 percent were self-employed and 17 percent were business owners.

Since the programme’s launch in January 2013, the bank has supported almost 20,000 women, investing nearly £2m in creating over 650 businesses, and played a critical role in getting entrepreneurial ideas off the ground. However, the bank is not alone in targeting women, and many more organisations are of the opinion that accessing finance is more difficult for women than it is men; not least Boost Capital, which has created a £10m fund for female entrepreneurs. Funding solutions such as Boost Capital and Inspiring Women in Enterprise represent only two of many well-meaning attempts to address the issue at hand, though the grant schemes ultimately fail to address the root cause of the problem.

Although the #GirlBoss foundation represents a fluffy and inexpensive version of the aforementioned European schemes, it boasts one key advantage: an entrepreneurial role model to fit in neatly alongside the funding. Studies show there are little to no gender-specific differences in funding for startups, and the terms offered to women are no different to those offered to men – at least not insofar as gender dictates. Still, women are less inclined to seek external financing, and, without entrepreneurial role models to offset the male bias, this reluctance to approach institutions will persist. Granted, role models alone are not enough to break down the obstacles standing in the way of women in business, but they do play a valuable role in affirming to aspiring entrepreneurs that the male-female imbalance is not enough to stifle success.

The #GirlBoss foundation represents an effective funding model wherein reinforcement is coupled with financial support. Assuming existing schemes can get appropriate role models on board and scale up the financial support on offer, the entrepreneurial imbalance that exists in Europe will begin to level out.