Back in April last year, Transport for London (TfL) invited companies to put forward innovative ideas designed to bring the disused Down Street underground station back to life by turning the site, which played an important role in the Second World War, into a commercially viable business.

The move is part of a wider plan to generate more than £3.4bn by redeveloping the city’s ‘ghost’ tube stations, including York Road, the old Highbury and Islington, and a deep-level air raid shelter at Stockwell.

TfL is hoping entrepreneurs and business leaders will see this as a golden opportunity to create a thriving enterprise in the heart of London, with the revenue it gains from the lease allowing it to reinvest in a transport network that will soon struggle to deal with the city’s growing population.

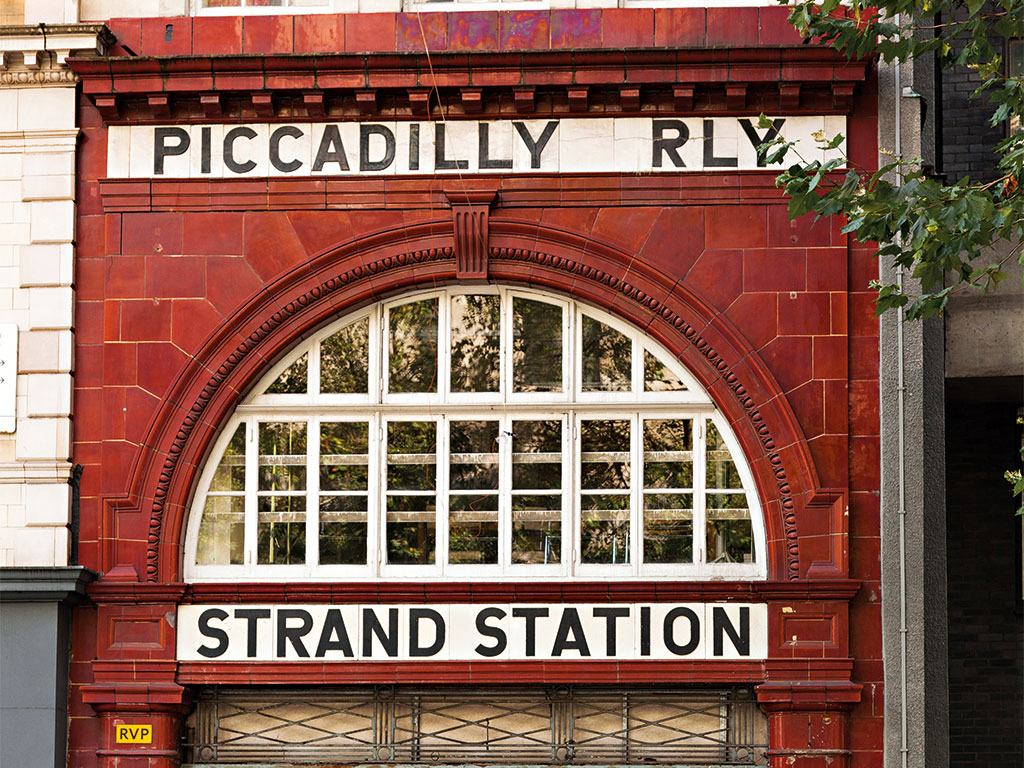

Down Street first opened on the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway nearly a century ago, only to close on May 22 1932 because of a shortage of passengers using the station on account of it being so close to Hyde Park Corner and Green Park stations.

TfL is hoping entrepreneurs and business leaders will see this as a golden opportunity to create a thriving enterprise in the heart of London

“The combination of space, history and location makes this a unique opportunity”, said Graeme Craig, TfL’s Director of Commercial Development, in a statement. “We are looking for a partner with the imagination to see the potential here and the capability to deliver it. Adjoining parts of the station are still required for running the Tube, but we will work with interested parties to ensure the commercial and operational activities can happily coexist.”

Since that initial announcement back in April 2015, very little else has happened with the project, with TfL yet to announce the winning bidder. The reason the transport authority is stalling on naming its choice, according to Ajit Chambers, a former banking executive at Barclays, who first proposed plans to renovate London’s abandoned stations and tunnels back in 2009, is because its procurement process for the project was unlawful.

Chambers is preparing to take legal action against the transport authority over claims that TfL “stole” his plan to reopen the city’s ghost stations to the public, in the form of tourist attractions, trendy bars and restaurants, and as venues for live music and other events.

In response to the accusations, a TfL spokesperson said: “Although Mr Chambers may be disappointed with our decision, we have held an open and fair procurement process. We will now enter into negotiations with our preferred bidder and hope to make an announcement shortly about the new commercial future of Down Street disused station.”

It is yet to be seen who will win the bid and what Down Street station will eventually become, but with many cities around the world experiencing a surge in urbanisation, more and more municipalities should follow London’s lead and look at maximising the utility of their forgotten infrastructure.

Parisian planning

A couple of years ago, Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet, a centre-right politician and Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP) party member, announced her intention to run for the 2014 Paris mayoral election. At the start of her campaign she was lagging behind in the polls to the Socialist candidate Anne Hidalgo and, therefore, needed to put forward a proposal that would turn the tide of the election and grab the attention of the electorate.

In the end, Kosciusko-Morizet opted to back a plan proposed by OXO Architectes and Laisné. The designers released a number of digitally rendered images that showed what the ghost stations of Paris could become with a little investment, with options varying from lush public gardens and swimming pools to privately owned nightclubs and theatres.

“Some emblematic places in Paris, such as L’Arsenal, Porte des Lilas, Porte Molitor or Champs de Mars, used to have namesake metro stations”, said OXO in a statement. “But, after closure, they slowly fell into oblivion. To swim in the metro seems like a crazy dream, but it could soon come true…an underground garden could be a place to enjoy calm and quietness on a rainy day, in a completely new environment.”

The head of the state-owned public transportation operator, RATP, told local reporters it would be near impossible to make the stations safe for public use

Sadly, the wonderful dream never did materialise, as the proposal, although gaining a lot of interest from the media, was not compelling enough to sway voters, and Kosciusko-Morizet was beaten by Hidalgo.

Since her defeat, very little else has been said about the regeneration plans, which at the time were criticised by some commentators over issues of cost and safety. In fact, the head of the state-owned public transportation operator, RATP, even told local reporters it would be near impossible to make the stations safe for public use as they are subject to stringent safety regulations. Not everyone has forgotten about the potential of Paris’ ghost stations, however.

“Why can’t Paris take advantage of its underground potential and invent new functions for these abandoned places?”, asked Manal Rachdi of OXO Architectes. “Far from their original purpose, more than a century after the opening of Paris’ underground network, these places could show they’re still able to offer new urban experiments. Turning a former metro station into a swimming pool or a gymnasium could be a way to compensate for the lack of sports and leisure facilities in some areas.”

Global potential

London and Paris are not the only major cities that could put their abandoned underground stations to work once more. Chamberi in Madrid was a prime candidate for a regeneration project similar to those proposed by its neighbours in Europe, and serves as a great example of what can be achieved when a good idea becomes a reality.

Chamberi was one of the eight original stations that formed the capital’s metro system. In the 1960s, in response to increased passenger traffic, local authorities decided to purchase larger trains that were capable of dealing with the increase in the number of people using the transport network. This had the adverse effect of making Chamberi station useless, as it was impossible to lengthen its platforms to cater for the newly commissioned trains. For years, the walls of the abandoned station were left for graffiti artists to tend to. But, in 2008, a solution was found to put the disused station to work once more: it was reopened as a living metro museum. The station was preserved in its final functioning state, complete with period advertising and lighting, offering visitors the chance to immerse themselves in the history of subterranean Madrid.

Urban regeneration of disused stations is financially enticing for sure, but sometimes it is best to leave a site alone. Take the Petite Ceinture, for example. This 20-mile stretch of abandoned railway was constructed more than 150 years ago in the heart of Paris. Due to its geographical location and the fact that the city is trying to tackle a housing crisis, developers would love the chance to build on the site. But, years of neglect by man have meant that nature has reclaimed the area for itself and environmentalists and animal rights activists argue that developing the line would destroy the wildlife that has made a home there.

Despite their protests, Hidalgo, the current Mayor of Paris, would like to see the Petite Ceinture converted into a commercial hotspot, with cinemas, aquariums and bars built. The owner of the abandoned railway, RFF (the French rail network), shares her vision and has already begun selling off sections. The economic benefit that sites like this and others around the world provide is huge. But while it is a travesty to leave them to sit vacant, municipal authorities must think long and hard before green-lighting any old project, as citizens deserve more than just another trendy wine bar.