Few industries are so bound by the trappings of family heritage, pride and larger-than-life characters as the world of big branded luxury. For Axel Dumas, the 47-year-old CEO of $40bn (€34bn) fashion giant Hermès International, family responsibility runs deep.

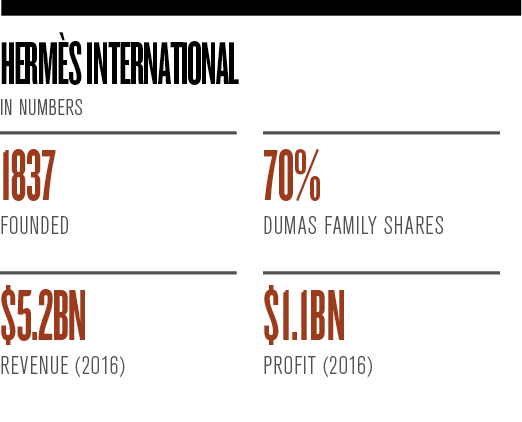

He is a sixth-generation member of the family that founded the Hermès brand, and his family retains control over the company to this day, collectively owning approximately 70 percent in share capital and forming a large part of the executive board.

Growing up, Dumas’ mother held the role of managing director, while his uncle, Jean-Louis, was CEO. His grandmother is said to have instructed him to protect the company while on her deathbed. It is inevitable, therefore, the family-centric nature of the business dealings at Hermès have shaped Dumas’ role.

Formidable foes

Dumas’ leadership has been defined, more than anything else, by his role in the infamous rift between his own family and the extravagantly wealthy Arnault family, which owns a majority stake in the $130bn (€110.3bn) Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) luxury conglomerate. The intertwined business dealings of the families only recently came to a close in April, when LVMH relinquished its final share in the Hermès enterprise. The move marked the end of seven years of fraught business dealings between the two families.

In the present climate, luxury companies are fighting to maintain the allure of scarcity while pushing for ever-increasing production

Talking to European CEO, Mark Tungate, author of Fashion Brands: Branding Style from Armani to Zara, noted Dumas fought off the LVMH takeover attempt with “both conviction and panache”. Dumas himself described the saga as the “battle of our generation”, when speaking to the Financial Times in a rare interview.

The feud dates back to October 2010, when LVMH announced – to the surprise of the Dumas family – that it had built up a 14.2 percent stake in Hermès. The group, led by Bernard Arnault, had acquired the stake using equity swaps, which allowed it to avoid declaring the stake in its legal filings. The move infuriated leadership figures at Hermès, who professed it to be the largest fraud in the history of the French stock market. While making a statement on Hermès’ profits, then-CEO Patrick Thomas came out with the infamously crude line: “If you want to seduce a beautiful woman, you don’t start by raping her from behind.”

LVMH staunchly denied its secret share accumulation was a takeover attempt, but the move would represent the first weave in a web of legal battles and formal investigations. The battle waged on for years, and was in full swing when Dumas took the role of co-CEO in June 2013 – a position he shared with Thomas for a short period before taking full control. Indeed, just two weeks into Dumas’ tenure, Hermès filed a landmark lawsuit against LVMH seeking the cancellation of the equity swaps it had used to secretly build up shares.

Ultimately, the Dumas family grouped together to guard company independence. Recounting the event to the Financial Times, Dumas said: “What was admirable is that the family really gathered herself to keep the independence of Hermès. We created a holding company called H51, which owns 51 percent of the company, where no one is allowed to sell their shares for 20 years.

“It was a big commitment for them to say ‘I will put all my net worth there and not sell it for 20 years’. But they did it – like that. It was a very strong mandate that they gave me – to keep Hermès independent – and it’s something that I’m focused on, regardless of the situation. It was a test of loyalty, yes. And I found it.”

The bad blood between the two families ended, for the most part, in 2014, when an intervention by a French court prompted LVMH to redistribute the disputed 23 percent stake to shareholders and institutional investors. It wasn’t until LVMH faced complications in its acquisition of Dior Couture, however, that the Arnault family finally relinquished its remaining financial foothold in the company – bringing the debacle to a resounding end.

Guarding the luxury ideal

But this intense family rift is not the only difficulty that Dumas has faced; leading a global luxury brand in the 21st century is a paradox-laden job. In the present climate, luxury companies are fighting to maintain the allure of scarcity while pushing for ever-increasing production. In financial terms, Dumas has presided over an impressive upwards streak in both profits and revenue. In 2013, the group’s revenue stood at $3.75bn (€3.2bn). This grew to $4.1bn (€3.5bn) in 2014, $4.8bn (€4.1bn) in 2015 and $5.2bn (€4.4bn) in 2016.

Profits, meanwhile, started at $780.4m (€662.4m) in 2013, and grew to $859m (€729.1m) in 2014, $972m (€825m) in 2015 and $1.1bn (€933.7m) in 2016. What’s more, the operating margin recently reached an all-time high, hitting a rate of 34.3 percent of sales during the first half of 2017.

During a time of mass expansion, Hermès has done a remarkable job of maintaining the draw of its brand. As Tungate said, Hermès has “managed to have its cake and eat it too”. Put a little more coarsely by Dumas himself, the company has sought to “grow bigger but not fatter”. The reason behind this success could be the company’s infamous ‘waiting list’, which ensures customers who order a Hermès handbag frequently have to wait upwards of two years before they receive it.

Often, people struggle to even get on the waiting list. The result is a buzz surrounding Hermès products that is rarely matched by the brand’s competitors. Tungate said: “I would argue that Louis Vuitton has lost some of its lustre through over-expansion – it has really become a mass luxury brand – while Hermès has retained careful control over its availability.”

And yet, despite clever tactics like the waiting list, the implications of global expansion are presenting a stubborn challenge to the sector. Giana Eckhardt, Professor of Marketing at Royal Holloway, University of London, said: “As luxury companies become globalised, it is becoming harder to demonstrate authenticity, heritage and craftsmanship, three of the main drivers of luxury consumption.

During a time of mass expansion, Hermès has done a remarkable job of maintaining the

draw of its brand

“Many Italian brands will say ‘designed in Italy’ rather than ‘made in Italy’ because they are made in Asia. But consumers know this and cannot relate as strongly to the Italian artisanship and design sensibility as they could when operations were more localised.”

For Dumas, the answer is a deep dedication to craftsmanship and an insistence on highly trained artisans. Eckhardt noted Hermès has also moved to combat the problem by investing in the development of more localised luxury brands, such as Shang Xia in China: “Chinese consumers can relate more to the form of authenticity and the type of artisanship that is displayed through these localised brands.”

Inconspicuous luxury

In any case, Eckhardt argues there has been a profound shift in the way brands are used as social signals: “If I see someone driving a BMW, how do I know if they own it or are accessing it via Zipcar? If I see someone using a Prada handbag, how do I know if they own it or are accessing it via Bag Borrow or Steal?”

Ultimately, luxury brands are no longer able to signal elite status in the same way they once did. As a result, Eckhardt believes the very nature of luxury is shifting towards inconspicuous branding, through which the significance of a luxury product is appreciated only by those who have some expertise on the matter. Eckhardt said: “If a high level of knowledge is needed to interpret brand signals – like recognising a particular type of heirloom tomato or an obscure craft beer – that facilitates the purpose that traditional luxury brands have typically filled: gaining social capital.”

While sales are high at present, a dominant chunk of Hermès’ income comes from its universally recognised bags. As these are far from inconspicuous, this implies that a difficult path may lie ahead for the company. However, Eckhardt suggests brands like Shang Xia could once again provide the answer: “Brands such as Shang Xia – where there is no visible logo and only those with a design and history background will be able to recognise the high level of craftsmanship – are examples of brands recognising the shift and are on the forefront of where luxury branding is heading in the future.”

Would-be philosopher

Faced with a range of fundamental challenges to the sector, it is notable that there is more to Axel Dumas than a mere hard-edged businessman. Tungate argues Dumas exhibits a particular mix of “toughness and romanticism”, which is a good combination for a CEO in the luxury industry. This romanticism was laid bare when Dumas said he would, given the choice, spend his time philosophising. “From time to time, I fantasise that I’m going to go back to my philosophy study,” Dumas told the Financial Times, when asked what he does in his spare time.

However, Dumas isn’t the only Hermès heavyweight to view the world with a philosophical slant: his cousin and Hermès’ highly regarded creative director, Pierre-Alexis Dumas, is also well known for his ruminations on the topic of luxury. Indeed, he was described by the few who have interviewed him as holding the “manner of a philosophy don”, and being “more like a scholar of Eastern philosophy than a creative director”.

This philosophical thread is no coincidence. In fact, Eckhardt aptly described why it makes good business sense: “Consumers want to buy a type of magic when they buy luxury products. This desire to seek out the best of mankind’s efforts from an aesthetic standpoint is something that a philosophical background allows you to understand and to tap into.

“Additionally, humans have always wanted to stand out from each other, in every society that has ever been studied. Luxury brands are a powerful way to do so in modern times, and a philosophy background allows you to understand this desire for hierarchies within human nature.”

Indeed, philosophy is one hobby that will stand Dumas in good stead when tackling the particularities and peculiarities of the luxury brand industry, especially as it faces the fundamental shifts ahead.