Despite the many advances made in the field of renewable energy, the developed world still relies heavily on fossil fuels for much of its power. Across the EU, this takes the form of a mixture of coal, oil and gas, which collectively accounts for around 75 percent of all energy consumed by the bloc.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) in particular represents a substantial portion of the EU’s energy mix, with consumption having increased steadily since 2014. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the use of LNG is likely to increase as the EU transitions to a decarbonised future. This is due to the fact LNG combustion produces up to 60 percent less carbon dioxide than coal, meaning it could provide an essential bridge to a low-carbon future if renewable technologies are not ready to take over just yet.

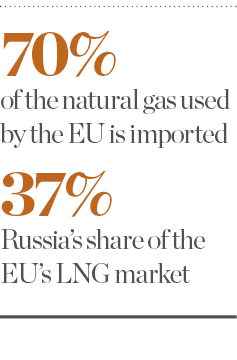

There is a problem with Europe’s turn towards gas, however: the continent does not produce enough of it. Currently, around 70 percent of the EU’s natural gas is imported and, more worryingly, most of it comes from Russia. And while the world’s largest country has been a pretty reliable supplier for a number of years, many are starting to question whether it is wise to be so reliant on a single producer.

Controlled by the Kremlin

US President Donald Trump is just one of several individuals to have warned about the dangers of Europe becoming too reliant on Russia for natural gas. Since 2014, Russia’s share of the EU’s LNG market has risen from 30 percent to 37, and there is potential for this figure to grow further in the future.

Europe’s reliance on Russia is a concern, regardless of whether Russian President Vladimir Putin plays fairly or not

Despite a long history of supplying the EU’s energy, Russia is viewed as an untrustworthy partner. Among a number of destabilising acts the country has committed – or, at least, been accused of – in recent years include illegally annexing Crimea, engaging in cyberwarfare, meddling in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum and helping to put Trump in the White House.

“The main problem that might arise due to Europe’s dependency on Russia for gas is one of vulnerability,” Andreas Silcher, a partner at international law firm Haynes and Boone, told European CEO. “Europe remains significantly at the mercy of Russia and possible supply disruptions. In case Russia decides to use the gas supply for political or commercial leverage, energy disruptions could leave Europe exposed to shortages.”

Whether or not one believes Russia would realistically cut off parts of the EU from its LNG supplies likely depends on one’s political point of view. Certainly, the fears could turn out to be little more than scaremongering or anti-Russian propaganda, but it should not be forgotten that Russia has stopped gas from flowing through Ukrainian pipelines on three separate occasions since 2006. It would not be unprecedented for political disputes to result in energy bottlenecks. According to Murray Douglas, a research director in the Europe Gas Research team at Wood Mackenzie, Europe’s reliance on Russia is a concern, regardless of whether Russian President Vladimir Putin plays fairly or not.

“Clearly, you can’t discount the political element, but I think with any commodity, once you approach the current level of dependency, it begins to raise some questions,” Douglas said. “This concern is not unique to Russia, but appears whenever a single supplier dominates over a third of the market. I think some of the EU member states would actually argue that Russia has proved to be a pretty reliable supplier for a number of decades – that’s certainly the case if you were to speak to some of the gas buyers within the German market. However, there have been less reliable moments – notably regarding disputes with Ukraine.”

Europe has gradually become more reliant on Russian gas over the past decade or so, and the question now is whether this dependency is set to persist or fall away as the continent’s demand for LNG increases. If Europe does look to other sources, how Russia reacts could make for interesting viewing. It may have to decide whether to prioritise higher gas prices or higher market share.

A pipe dream

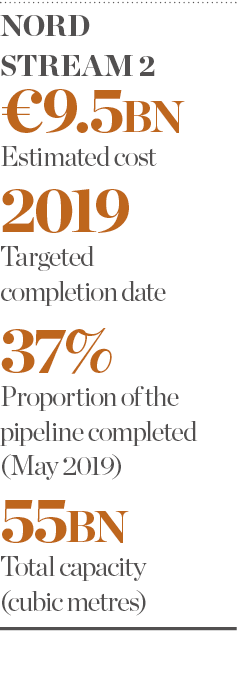

Complicating matters between Russia and the EU is Nord Stream 2, a new gas pipeline project running across the Baltic Sea that will connect the two parties. The pipeline, which will have a total capacity of 55 billion cubic metres of gas per year, is scheduled to begin operations before the end of 2019, but criticism from European states and the US has resulted in delays and even calls for the project to be scrapped.

“Currently, public opinion over the Nord Stream 2 project is divided,” Silcher explained. “On the one hand, it will satisfy increasing gas demand immediately and gas liquidity will be enhanced in Central European gas hubs. On the other, it undermines energy security and increases dependency on Russia. It minimises diversification of energy and undermines the bloc’s gas market competitiveness.”

At the time of European CEO going to print, the Nord Stream 2 project is around 37 percent complete, but physically laying the rest of the pipeline is not the only challenge on the horizon. The European Council’s decision to approve a new gas directive amendment in April 2019 is set to have significant ramifications for Nord Stream 2. In fact, it will mean that, despite being a non-EU pipeline, it will have to abide by EU rules.

In order to achieve compliance, Gazprom – the state-owned Russian petrochemicals firm that is the sole shareholder in the project – would have to unbundle the pipeline or hand over operations to a third-party Russian gas supplier. Either option is likely to take time and could result in the pipeline remaining underutilised – for the initial years of operation, at least – which would damage its economic viability.

“We believe that the project will definitely come online,” Douglas said. “Certainly, some EU member states remain opposed and hope that it gets cancelled altogether, but that is very unlikely in our opinion. There does remain a lot of uncertainty and there could be some delays, but our base case still assumes that the pipeline starts by early 2020.”

Adding to the uncertainty is the fact that the Danish Energy Agency has requested that Gazprom submit a third application for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline route. Although the initially proposed route follows that of the first Nord Stream gas pipeline, there is still a risk that Denmark could veto it. A second proposal shifted Nord Stream 2 north-west of the Danish island of Bornholm, while a third option would take the pipeline further south of the island, avoiding Denmark’s territorial waters, but remaining in the country’s exclusive economic zone. While Denmark has not rejected any of the routes on the table as of yet, delays are expected. In particular, if a full environmental assessment of the third route is requested, then gas flows may be pushed back even further.

Heading south

Nord Stream 2 is a huge project and too many organisations have committed vast amounts of time and money to see it mothballed. Uniper, Wintershall, ENGIE, OMV and Royal Dutch Shell have each provided €950m, with Gazprom contributing the rest of the project’s €9.5bn cost. However, the new pipeline alone may not be enough to meet Europe’s growing LNG demands.

One method the EU could pursue in order to diversify its gas supply is the creation of the Southern Gas Corridor, a project that would take Russia out of the equation completely. Such a proposal would look to bring gas into the EU from the Caspian basin, Central Asia, the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean basin. In theory, this could supply Europe with between 80 and 100 billion cubic metres of additional gas. In practice, though, generating such flows will be challenging.

“I think some of the good news previously centred on Romania having success over the last few years in the Black Sea, but now there’s some uncertainty over those projects, particularly the development known as Neptun Deep,” Douglas said. “There’s also [the EastMed] proposal that would take gas onwards into Italy – that’s a very technically challenging project and the pipeline itself would be incredibly expensive, so there’s some uncertainty regarding what to do with the [EastMed] gas.

“Some of it is being taken back into Israel and some of it is being taken south into the Egyptian market to restart LNG exports there. If Cyprus wants to monetise some of that gas, it probably needs further discoveries and we believe it’s more likely that Cyprus would actually develop its own LNG facility rather than take that gas into an [EastMed] pipeline.”

The problems are political as well as technical. Although there is much discussion over Russia’s disruptive influence, it is, at least, a single country with self-interest as its primary concern. The same cannot be said for the Southern Gas Corridor, as the EU must consider the various parties involved – what garners approval in Azerbaijan may not find favour with Albania, for example.

“In order to develop a Mediterranean gas hub further, the EU needs to do three things,” Silcher said. “On a political level, the bloc should engage in constructive dialogue with the relevant countries to foster good relations and cooperation with the relevant North African and Eastern Mediterranean countries. It must invest in infrastructure development plans, including pipeline networks and regasification facilities. And it should maintain the infrastructure projects listed as Projects of Common Interest that will receive preferential regulatory treatment, EU funding and [accelerated] permitting processes.”

Geopolitical tensions in several of the countries that could play a role in the Southern Gas Corridor mean that potential backers are likely to view gas developments in this part of the world as high-risk investments. It is also true that these proposals will take a significant amount of time to negotiate and even longer to construct. With every passing day that these projects remain at the exploration stage, Russia’s dominance of the EU’s

gas market strengthens.

Needs must

The fact that gas production within the EU has fallen recently makes it more difficult for member states to escape Russian influence. In particular, the collapse of production at Europe’s largest gas field in Groningen, the Netherlands, has caused domestic supply to take a sharp hit.

With internal supply falling and demand on the rise, the EU has little choice but to look outside its borders for natural gas. Although recent internal discoveries, like those off Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, will prove useful, they won’t be enough on their own. The US – now the world’s largest producer of natural gas – could plug some of the gaps, particularly with the country aiming to expand its export capacity beyond 90 billion cubic metres by the end of the year.

Even so, it is difficult to see Europe meeting its LNG needs without Russia playing a significant role. The challenges to developing other gas projects do not mean that the EU should abandon efforts to diversify its energy sources, but it should also remain realistic. Russian gas, particularly with Nord Stream 2 set to come online sooner rather than later, is unlikely to go away.