SAP has set itself an ambitious recruitment target: by 2020, the German software giant hopes to hire 650 people with autism, a number that represents one percent of the firm’s workforce. This isn’t a corporate social responsibility push, nor is it something the company is doing to give back to the community. Rather, it is an initiative built upon business logic.

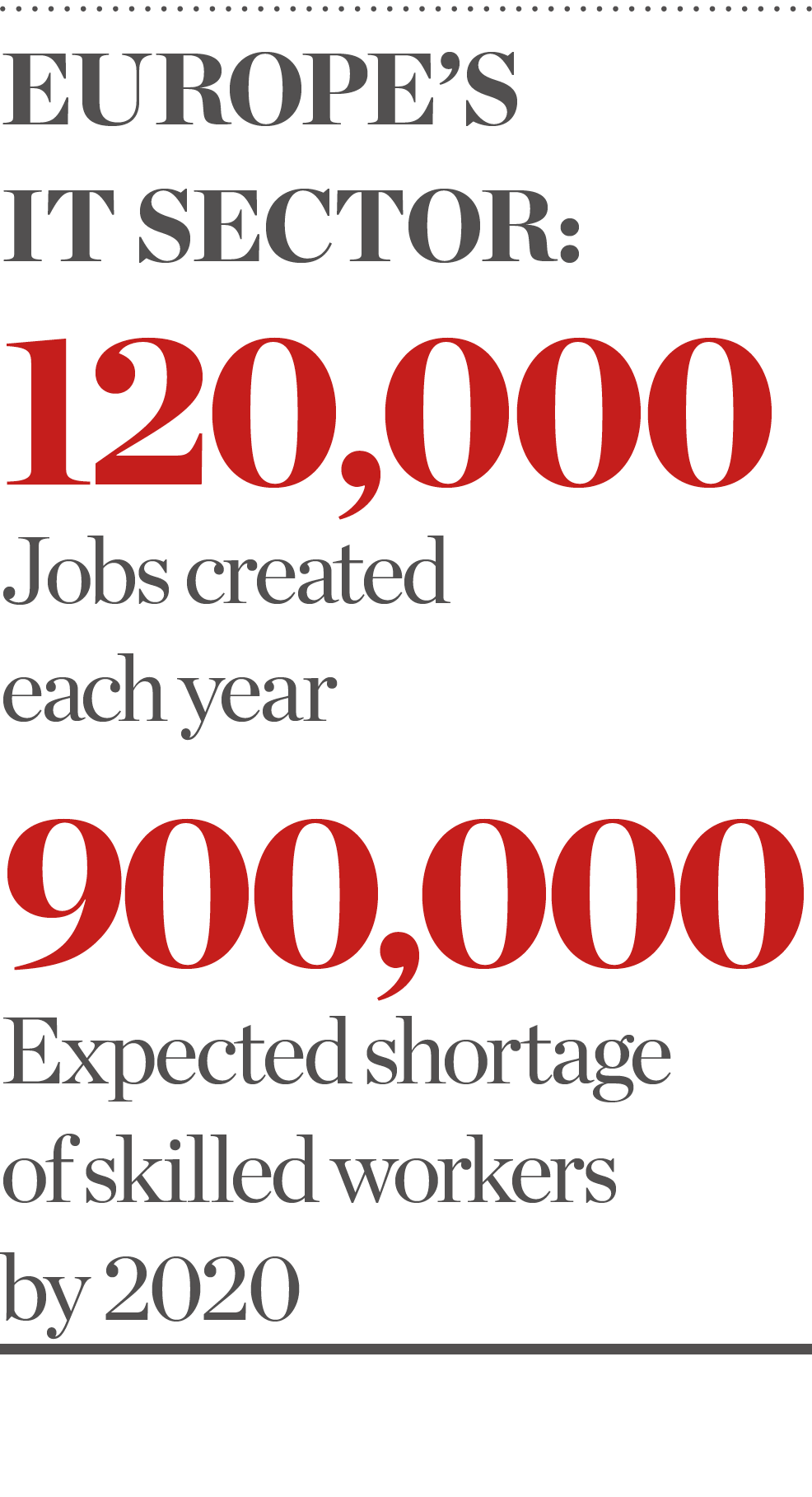

“[People with autism] can be very creative, think outside the box, have strong research skills and possess excellent attention to detail,” Geraldine Leader, Director of the Irish Centre for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Research, told European CEO. Right now, such a skill set is in high demand. Businesses around the world find themselves facing a shortage of tech talent: according to the World Economic Forum, only 27 percent of small companies and 29 percent of large companies believe they have the talent required to carry out a digital transformation. In Europe, the IT sector is currently creating around 120,000 jobs each year; with a dearth of emerging talent in the field, the industry is expected to be short of 900,000 skilled workers by 2020.

While people with autism may struggle in certain social situations, they can excel in other areas of professional life

Many of the unfilled positions are expected to be in data analytics and IT services implementation. These rapidly expanding fields are areas in which someone with autism could flourish, and major companies – including Ernst & Young, Microsoft, JPMorgan Chase and SAP – are starting to wake up to the untapped potential of people who live life on the spectrum.

An open mind

In recent years, diversity has climbed the corporate agenda, with employers recognising the importance of having a workforce that represents different genders, religions and ethnicities. When it comes to conditions like autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia, though, companies have been much slower to level the playing field. According to the UK’s National Autistic Society, 60 percent of employers admit to not knowing where to go for support and advice about employing an autistic person.

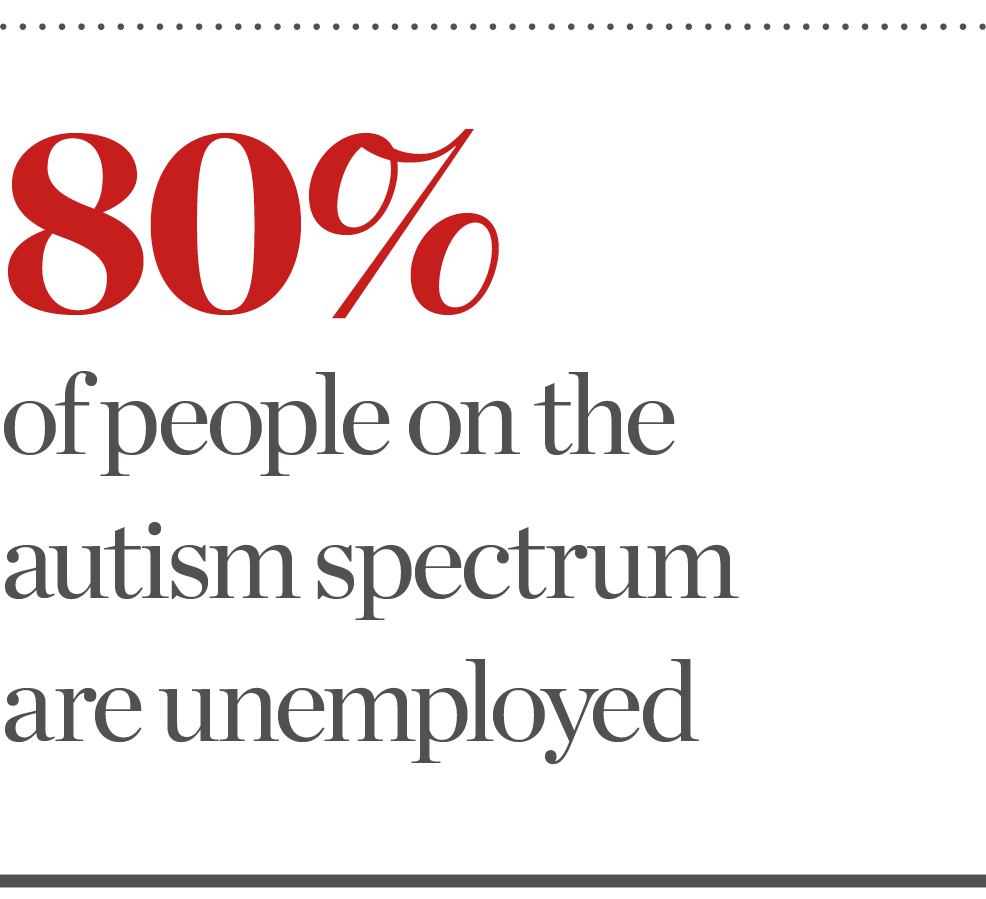

This lack of awareness can have significant consequences. Globally, the unemployment rate for people on the spectrum stands at 80 percent – a staggering statistic when you consider the broadness of the condition, which ranges from people with severe autism, for whom a normal working life may never be possible, to those with far milder conditions such as Asperger syndrome, which was incorporated into the wider autism spectrum in 2013. But despite the huge variation in individuals’ conditions, poor social skills are a common feature. “People with autism may have difficulty with social communication and social interaction,” Leader explained. “They may find it difficult to navigate the complexities of non-verbal and verbal language, and take what people say very literally.”

But while people with autism may struggle in certain social situations, they can excel in other areas of professional life. For instance, they may feel less daunted by the prospect of pointing out the flawed logic and white lies many of us accept in social circles and our everyday lives. Some, including The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf, have argued that this can make those on the spectrum very effective whistleblowers.

It’s also true that people with autism tend to become deeply engrossed in the subjects they enjoy, and this can help them become experts in their chosen field. When SAP launched its Autism at Work programme, applicants included individuals with master’s degrees in electrical engineering, biostatistics and economic statistics, as well as bachelor’s degrees in computer science and applied and computational mathematics. “This is a group of people who are not thriving on the paradigm of a generalist, but… can thrive under the paradigm of specialists,” Thorkil Sonne, the founder of Specialisterne, a Danish social innovator company that helped launch the Autism at Work programme, said in a podcast in 2018.

While people with autism may struggle in certain social situations, they can excel in other areas of professional life

The absence of autistic people in the workplace perhaps demonstrates a wider trend in hiring processes. Employers have come to glorify the ‘well-rounded’ employee, with job postings often containing a shopping list of desired traits – such as good communication skills, an analytical mind and leadership potential – even when some of the attributes are not strictly required for the role. This can disadvantage people with autism, who are unlikely to tick all of those boxes but can nonetheless prove highly valuable members of a given workforce.

Word on the street

Gradually, people are starting to talk more openly about autism, and with less prejudice. This is partly thanks to high-profile figures like 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg, who has Asperger’s, and awareness-raising initiatives promoted by major companies, but it’s also down to the wider neurodiversity movement. Supporters of this movement put forward that neurological differences such as autism should be celebrated, not shunned, by society.

However, it has also been a source of conflict within the autistic community. While some celebrate their autism as a gift, others view it as something that should be treated. US TV show Sesame Street found itself at the heart of this conflict in 2017 when it introduced a Muppet character named Julia who displayed some of the attributes of a child with autism. At first, many people from the autistic community commended the show for the move, but it later provoked outrage when the Muppet became the face of an Autism Speaks public service campaign encouraging the early screening and diagnosis of autism. The partnership fell through after members of the autistic community spoke out, accusing both Sesame Street and Autism Speaks of perpetuating a stigmatising attitude that sees autism as something to be ‘cured’ rather than celebrated.

Other members of the community have taken a very different perspective. Some families and self-advocates point out that, by condemning the treatment of autism, neurodiversity supporters may be inadvertently marginalising those who are severely autistic. With the autism spectrum being as broad as it is – some people with the condition are very high-functioning while others are seriously debilitated – employers must seek to understand the many different perspectives within the community before implementing any initiatives that champion autism at work.

Making inclusivity work

When searching for employment, people with autism can often fall at the first hurdle: the interview. For someone with a limited ability to pick up on social cues, verbal tests can prove highly stressful. However, there are ways in which companies can make interviews easier: for example, avoiding indirect and hypothetical questions such as “what kind of animal are you?” will give people with autism a better chance of answering confidently.

There are also small changes that employers can make to ensure their workplace is more accommodating. Many autistic people suffer from sensory overload, meaning certain stimuli within the environment, such as loud sounds or strong smells, become distracting or even stress-inducing. Removing fluorescent lights or overpowering air fresheners can make an office space much more comfortable for someone with the condition.

When it comes to managing an employee with autism, direct and precise instructions are important. Some autism experts recommend that managers follow up meetings with written instructions that employees can refer back to. “In an employment situation, people with autism will work best when their role and what is expected of them is very clear,” Leader said.

Despite efforts to the contrary, autism remains an uncomfortable topic at work. This ultimately creates a wall of silence around the condition, one that can be detrimental to the efforts of bringing more people with autism into the workplace. After all, employees are usually happy to accommodate the needs of other staff members when they understand the everyday challenges they face. An inclusive attitude is not a luxury: it’s a key pillar of any company that wants all of its employees to thrive.