The UN estimates that by 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will live in cities. Transport networks aren’t prepared for the strain this will place on their services, and the infrastructure changes needed to expand those networks are incredibly expensive. As cities look into new ways to reduce congestion, a growing number of companies are turning their gaze skywards.

The race to develop the world’s first commercial air taxi service is on. In May 2019, consulting firm Roland Berger revealed that more than 170 companies are currently developing electrically powered aircraft. Half of these are focused on creating urban air taxis. A number of major firms have thrown their hats into the ring, from aircraft-makers to automotive giants. Early in October, Porsche announced it was working with aircraft-maker Boeing to develop a prototype flying taxi. Meanwhile, Hyundai has hired a NASA engineer to run its air mobility division, and Uber Air expects to commence test flights in 2020.

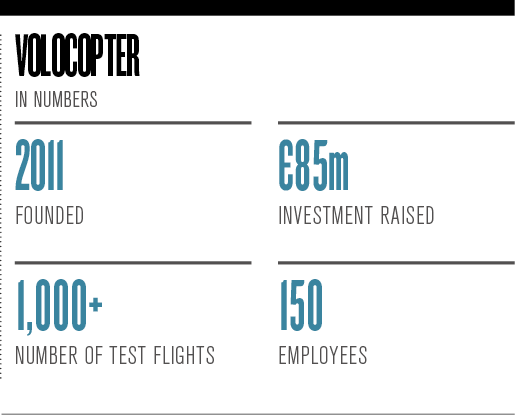

Despite competition from some of the biggest names in transport, one of the companies to enjoy the most success in this pioneering industry is German start-up Volocopter. Its flagship vehicle, the VoloCity, is an electrically powered, 18-rotor passenger drone, designed to carry two people and their luggage at a top speed of about 109km/h.

The air taxi recently completed its maiden flight over Singapore’s Marina Bay, where Volocopter hopes to commercially launch as early as 2021. In a press release, CEO Florian Reuter called it “the most advanced Volocopter flight yet”. He added: “Never before have people been this close to experiencing what urban air mobility in the city of tomorrow will feel like.”

Not long before the flight, the company had closed €50m in a Series C round of funding led by Chinese automotive company Geely, bringing its total funding to €85m. Other major firms that have invested in the company include Daimler, the German carmaker that owns Mercedes-Benz, and technology giant Intel. Each own around 10 percent of Volocopter, which they’re betting will be the first company to take this cutting-edge technology to the skies.

A new way to ride

When Reuter first joined the company as managing director in 2015, he was its fifth employee. Since then, the company has grown rapidly. It now has 150 members of staff across offices in Bruchsal, Munich and Singapore, but perhaps the biggest testament to Reuter’s strong leadership is the fact that many of the company’s crowning achievements have happened under his watch. In 2016, the firm received its first meaningful flying permit from the German aviation authorities, and in 2017, it completed its first autonomous test flight, launched by Dubai’s Crown Prince, Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed Al Maktoum.

In part, Reuter owes this success to the wealth of experience he gained by working closely with start-ups. Prior to joining Volocopter, he worked on the other side of the coin as a venture manager for Siemens, nurturing start-ups and helping them take their technology from the concept stage through to commercialisation.

“Eventually, I realised that what I really wanted was to join a start-up. That’s just when Volocopter came knocking,” he told Brunswick Group in 2018. “The idea of an electric helicopter – a drone scaled up for humans – that clicked with me. If I was going to put my heart and soul into a start-up, it would have to pursue something as exciting as this.”

As cities look into new ways to reduce congestion, a growing number of companies are turning their gaze skywards

For a long time, the concept of a flying car was confined to the pages of science fiction books. But in recent years, air taxis have come on in leaps and bounds, largely thanks to technological advancements made in the industry. “The key technology enablers are the size and weight reduction of electrical technology and more advanced control systems,” David Debney, who heads up whole aircraft technology at the Aerospace Technology Institute, told European CEO. “This has enabled what is known as ‘distributed propulsion’, which means the aircraft has more thrusters than engines. In the past, this was a one-to-one ratio for a number of design reasons. Increasing that ratio means vertical take-off and landing can be achieved in a more efficient manner.”

Initially, Volocopter’s air taxis will have human pilots, but the goal is for the vehicles to become fully autonomous. As part of its plans to commence operations in cities, Volocopter also wants to build landing hubs with the help of its partner Skyports. Dubbed VoloPorts, these landing hubs would negate the need for massive infrastructure investment, meaning Volocopter could be integrated into cities with limited disruption. Landing bays parked on top of city buildings – named VoloHubs – would operate like ski lifts, allowing Volocopter to process large volumes of passengers every day. Although the air taxis will only be used for singular routes at first, Reuter envisions these routes growing into networks, offering a new mode of transport as ubiquitous as travel by train or car.

Needless to say, the company’s vision is ambitious. Despite the pie-in-the-sky thinking needed to put such a transformation in motion, Reuter is, at heart, a pragmatist. Compared with disruptors like Uber – infamous for crashing into markets and quickly running into trouble with regulators – Volocopter has taken every measure to ensure its careful arrival into cities. The company has completed more than 1,000 test flights and is working with city officials, regulatory authorities and private companies to get its multicopter off the ground. Reuter also stresses the importance of working with telecommunications companies: in his eyes, 5G is crucial to scaling the technology as customers are unlikely to board a Volocopter to get to the office every day if they can’t access their emails or get online during the journey.

Turbulent times

Despite the progress that companies like Volocopter have made, some doubt the commercial viability of urban air mobility. Integrating a new transport system into a city is a logistical nightmare, and some critics are concerned that the simple fact an air taxi can’t land directly in front you, as an ordinary taxi can, will limit the technology’s appeal among the wider population. Richard Aboulafia, Vice President of Teal Group, argues that air taxis are little more than glorified helicopters; he doubts that the technology will ever make it to the mass market.

“Right now, there is an urban air mobility market that uses turbine helicopters. Last year, it was worth $351m [€315.72m]. There is a chance that air taxis could stimulate that market. But you’re still talking about an anecdote in the broader aerospace industry, which is worth about $900bn [€809.53bn],” Aboulafia told European CEO.

While the perception of air taxis as toys for the rich is a significant barrier to their widespread adoption, an even more significant barrier is their price. A report by investment bank Citigroup predicts an air taxi ride will cost about $6.04 per kilometre (€5.43), which it says is cheaper than a limousine but double the cost of ground-based ride-hailing. Unless air taxi services can reach a similar price point to that of taxis and trains, it will remain the preserve of the wealthy.

Volocopter is adamant its technology will become affordable for the average commuter

But Volocopter is adamant its technology will become affordable for the average commuter. Reuter predicts that, after five to 10 years, the cost will be equivalent to hiring an ordinary taxi. “The goal was always to democratise flying,” he told TechCrunch.

Barriers to entry

Another issue that could have a big impact on the technology’s appeal among the general public is noise pollution. City officials and residents alike will undoubtedly resist air taxis if the sound of them taking off and landing becomes an annoyance to communities. “The industry is working hard on ways to minimise this,” said Debney. “Current estimates are that these vehicles could be around 75 percent quieter than a helicopter.” From a distance of 100 feet, a landing Volocopter is only slightly louder than average road noise in New York, according to Volocopter’s whitepaper.

Another obstacle that Volocopter needs to overcome is the sheer amount of regulation within the aviation industry. Test after test is required to ensure the vehicles comply with different markets’ rules on things like operations, maintenance and noise pollution. And even if a vehicle passes all of these tests, airspace management remains a key issue: aviation regulators are currently unprepared for a flood of private air taxis taking to our skies. “At present, we have air traffic controllers guiding aircraft through the skies, and this system cannot be scaled up to cope with the projected number of flights that urban air mobility will create,” said Debney.

The seal of approval

Certain cities are likely to be prepared for this transition much sooner than others. One of the reasons Dubai and Singapore are being touted as the first air taxi hubs is because they are actively embracing the concept of an autonomous air taxi and adapting their regulation to this end. From Debney’s perspective, regulatory compliance is key to determining which companies in this space can gain a competitive edge.

“It is important that companies engage with regulators at the earliest opportunity,” he told European CEO. “Changes in user requirements could drive major changes into how the vehicles are designed… As cost is a big market driver, having the vehicle design closely matched to user requirements could prove to be a key differentiator.”

In this fledgeling industry, reliability is everything. Earlier this year, when Volocopter unveiled VoloCity, it was the fourth generation of its multicopter. The first three were developed just for flight and demonstration purposes, but this latest model is designed for commercial use. The fact that the company is on its fourth model demonstrates that it is treating regulatory concerns as a top priority. Further, the firm recently added a stabiliser to ensure it met safety standards set by the European Aviation Safety Agency.

Industry experts predict that there won’t be a mass market for flying taxi services until the 2030s. However, Citigroup reports that they could be available in Singapore and Dubai by 2025. Currently, Volocopter is ahead of the game in terms of providing a clear vision for an urban air mobility ecosystem. For a technology as pioneering as the air taxi, a steady leader who can help the company deliver on its promises is needed in order to win investor confidence and gain regulatory approval. Reuter has proved he can rise to the task.