The rest of the world is obsessed with China – and with good reason. The East Asian country is the planet’s most populous, boasts the second-largest economy and has ranked first in terms of contribution to global growth since 2006, according to its National Bureau of Statistics. The US has responded to this growth in an antagonistic fashion, launching accusations of unfair trading practices and imposing billions of dollars’ worth of tariffs. But the US’ loss could be Europe’s gain – if the continent can strengthen its economic ties with China, that is.

On a governmental level, this process is unlikely to be straightforward. Italy may have joined the Belt and Road Initiative last year, but many other nations have sent mixed messages regarding China’s ambitions, with concerns largely centring on privacy and national security. Some will find China’s wealth impossible to turn down; others are more likely to take an ethical stand.

For Europe’s private businesses, though, intergovernmental discussions between Beijing and Brussels form little more than background noise. The ability of the continent’s firms to forge relationships with their Chinese counterparts will depend as much on personal interactions as it will on political developments. Here, new difficulties lie in wait.

Chinese and European leaders must remember that developing good guanxi is a process – it takes time and needs constant maintenance

Many of the European organisations that have tried to make inroads in China have been met with insurmountable challenges. Italian fashion house Dolce & Gabbana, for example, has struggled to rebuild its reputation in the country after a controversial advertising campaign, while German supermarket chain Metro announced last year that it would sell off its Chinese units following “drastic changes” in the market. Many other western brands have encountered similar struggles.

European businesses often argue that cultural differences lie at the heart of their difficulties, making forging strong business relationships in China particularly challenging. Getting this right relies on an idea that is little known to the outside world: guanxi. Without getting a grasp on this concept, even the best businesses are likely to fail.

Open for business

In 1978, after years of strict state planning under Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, China’s economy underwent a period of opening up. At that time, then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping embarked on a series of economic reforms – dubbed ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ – that combined Marxist-Leninist thought with the kinds of market-orientated policies that had long been employed in the West.

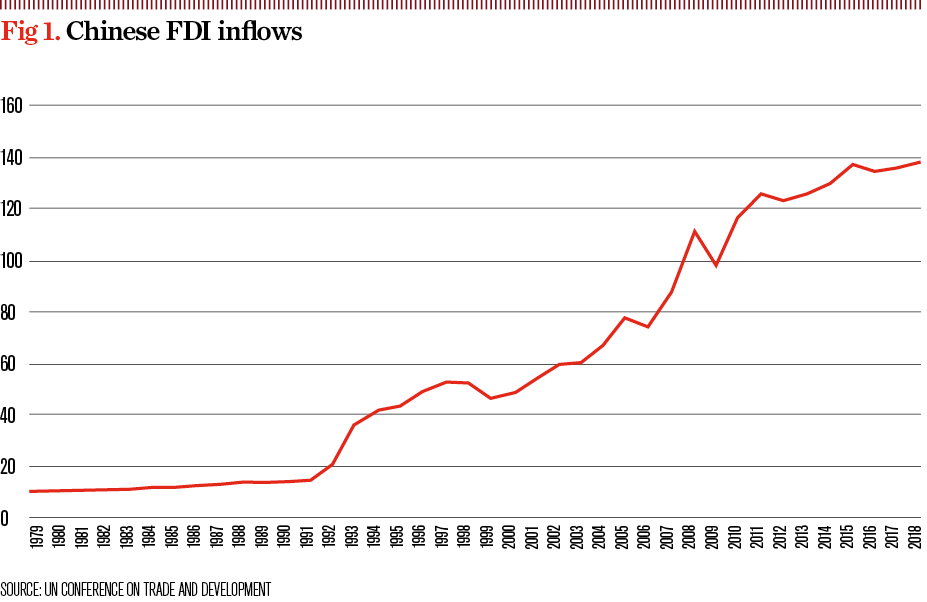

Deng’s reforms had a profound impact on the country’s fortunes: poverty fell rapidly, dropping from nearly 90 percent in 1981 to just two percent by 2013. GDP per capita, meanwhile, multiplied by a factor of almost 24 between 1978 and 2017. These improvements were partly fuelled by China reintegrating with the global economy: in July 1979, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Joint Ventures Using Chinese and Foreign Investment was passed, opening the country up to foreign direct investment (FDI). Initially, FDI inflows remained subdued, averaging $1.8bn (€1.45bn) per year between 1979 and 1991. However, FDI exploded in 1992 – reaching $11bn (€9.94bn) – and has continued to expand rapidly since (see Fig 1).

Since China opened its doors, international businesses have flocked to the country. Today, despite less-than-ideal geopolitical conditions, European firms remain committed to the market. According to the EU Chamber of Commerce in China’s European Business in China: Business Confidence Survey 2019, the country remains in the top three current and future investment destinations for 62 percent of the European firms surveyed.

“In spite of the volume and complexity of the issues that European companies face when doing business, the Chinese market remains integral to their future plans and they are dedicated to finding ways to expand their operations in the country,” the report read. “European companies have also continued to perform well, with strong profits recorded for 2018, as they are used to operating in challenging conditions against strong competition.”

Given China remained largely isolated under Mao’s Cultural Revolution, it is hardly surprising that the country has developed different business values to European firms. But an understanding of the nuances contained within these values and how they are likely to play out across boardrooms and breakout areas cannot be gleaned from afar – European firms looking to crack China will need to spend time, effort and money understanding the mechanics of doing business in the country.

East meets West

The first thing new entrants to China should do is make an effort to understand the concept of guanxi. Take a look at any prosperous business based anywhere in the world and personal relationships play an important role.

A good idea and a truckload of cash are not enough to guarantee success – people ultimately decide whether a company does well or not. This is also the case in China, but that doesn’t mean what works elsewhere will prove effective in the meeting rooms of Beijing or Shanghai.

“Guanxi is widely accepted in academia as an indigenous construct from China, deeply rooted in Chinese culture and reflected in the behaviour of Chinese people,” explained Barbara Wang, Associate Dean for China Initiatives at Hult International Business School, in her book, Guanxi in the Western Context: Intra-Firm Group Dynamics and Expatriate Adjustments. “According to a widely accepted definition, guanxi is ‘the closeness of a relationship that is associated with a particular set of differentiated behavioural obligations based on social and ethical norms’.”

In China, having good guanxi often relies on creating a strong network of relationships that, although beneficial in the corporate world, are cultivated in less formal settings, such as evening meals or nights out. “Guanxi practice is… conceptualised as affective attachment, inclusion of [one’s] personal life into workplace [relationships] and predominantly non-work-related social exchange acts, such as personal favour exchange, gift giving and dinner invitations,” Wang wrote. “The major difference between the Chinese guanxi measurements and the western social exchange is that the former includes social exchanges outside work whereas the latter is limited to personal relationships at work.”

The reciprocity inherent in guanxi can also catch western firms out. If an individual delivers a favour » for another party in China, there is an expectation that they will receive one in kind. Other differences have emerged slowly, stemming from deep-rooted social, ethical and philosophical norms.

A good idea and a truckload of cash are not enough to guarantee success – people ultimately decide whether a company does well or not

“Guanxi is the hierarchical human moral relationship derived from Confucian ethics for the purpose of long-term reciprocity, obligations and mutual benefit grounded in the affection-based trust among all actors in the circle initiated by one person at a time,” Wang told European CEO. “The purpose of guanxi practice is more specific and clearer than that of networking in terms of achieving a personal goal or favour. How many people you can connect with might be quite important for western networking, yet whom you… connect with is crucial for guanxi practice. In a nutshell, western networking is more like a ‘numbers game’ and guanxi practice is more like a ‘members game’.”

Of course, some European companies operating in China are already displaying an appreciation of guanxi. Several have focused their recruitment efforts on well-connected local talent – particularly concerning senior positions – to establish good relationships with key stakeholders. For more firms to find success, they will need to grasp the finer details of guanxi, learning to value personal loyalty over corporate relationships and form partnerships that are motivated by both social and economic concerns.

Quid pro quo

The personal loyalty that forms such an important strand of guanxi is not unequivocally good. There have been reports of guanxi encouraging corruption, with deals carried out far from the prying eyes of regulators. A cynical appraisal of the concept would suggest it differs little from the western idiom: “I scratch your back, you scratch mine.”

“The downsides of guanxi include that, as part of a process of profit-seeking, firms with the right connections can produce abnormal gains for themselves,” Wang noted. “It may involve paying bribes in order to obtain good deals from transaction partners or to persuade [the] government to help control competitors, and can often be seen as an impediment to economic growth because it stifles competition, does not allow for efficient allocation of capital, prevents the right kinds of investments from being made and leads to transaction breakdown due to opportunism.”

The anti-corruption campaign initiated by Chinese President Xi Jinping shortly after taking office – a drive that has been criticised as little more than a purge of his rivals – may result in the rule of law being reinforced in all aspects of Chinese life, curtailing the likelihood of guanxi-led immorality. Even so, guanxi is likely to remain a slightly murky area. Deals that may not be 100 percent above board, or that appear corrupt from a western standpoint, might not be viewed as culturally wrong in China – an ambiguity that will always be open to abuse.

“Watch out for companies that rely solely on guanxi to do business, ignoring genuine commercial opportunities simply because the relationships aren’t there,” Alex Barton, Managing Director (Greater China) at Intralink, told European CEO. “Guanxi can get you into difficult situations, where you may be forced to choose between doing somebody a favour [that] compromises your principles or damaging your guanxi by refusing.”

The ethical dimension is particularly interesting given that Chinese attitudes to privacy, individualism and human rights can differ markedly from those displayed in the West. For European businesses, the temptation to dilute their ethical stance to gain access to the populous Chinese market can be too great to turn down.

According to the Business Confidence Survey, approximately 20 percent of European businesses feel compelled to hand over their technology when working with Chinese partner firms. These companies may have developed a good relationship with local operators, and their financial situations might be in rude health as a result, but their digital solutions could eventually be co-opted for morally dubious means. That is still a cost, even if it doesn’t show up on the quarterly balance sheet.

A common language

To ensure European firms don’t find themselves undone by a culture clash when operating in China, the creation of diverse management teams that have a strong appreciation of both markets is essential.

“It is always helpful to have people who understand the culture that a company is dealing with engaged at the top level, if at all possible,” Catriona Llanwarne, a senior associate in Burness Paull’s corporate finance team, explained to European CEO. “China, in particular, is a complex country and its business practices have deep cultural roots, such that it cannot be fully appreciated without some investment, and engaging culturally diverse management can be a particularly effective way of doing this. Diversity at management level can be beneficial from a number of perspectives, and particularly so when trying to ensure a proper understanding of the issues faced

in dealing with a culture as different as China’s.”

Wang has developed a four-part model of cross-cultural guanxi that should help both Chinese and European business leaders communicate effectively and avoid misinterpretation. The first strand of Wang’s model is situational and takes into consideration the context surrounding an emotion or rational connection.

European firms looking to crack China will need to spend time, effort and money understanding the mechanics of doing business in the country

The second concerns inclusivity and relates to the way guanxi actors often discount individuals outside of their inner circle – to achieve better synergy with western companies, Chinese firms should initiate guanxi practices with external partners. The third strand is heterarchical, suggesting Chinese leaders should be careful to adapt their hierarchical approach with sensitivity to local norms. Finally, Chinese and European leaders must remember that developing good guanxi is a process – it takes time and needs constant maintenance.

There are more general strategies that corporate leaders could adopt to help them form bonds with individuals from other cultures, too. Using a common language in the workplace, especially in meetings, helps to build trust, while displaying an open mind helps when dealing with cultural differences. Treating people equally in the workplace is universally respected in business, whether it’s being conducted in Europe, China or elsewhere.

Outside, looking in

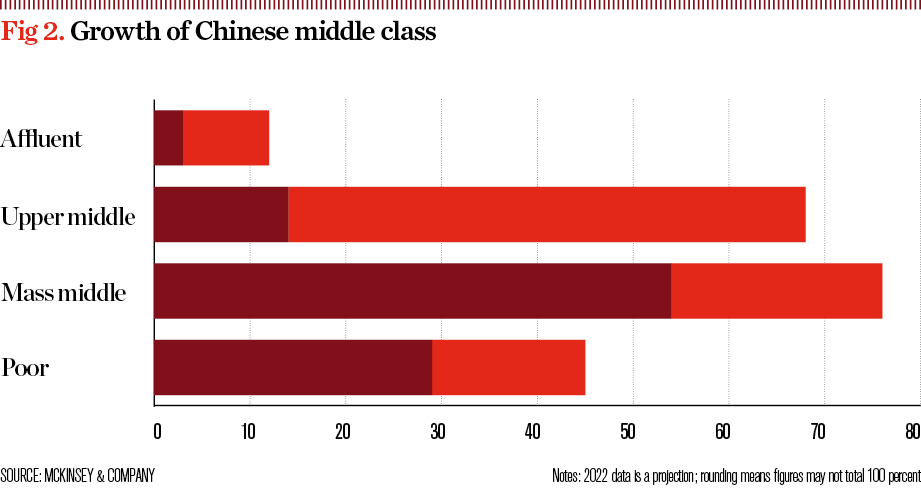

China has a population of more than 1.4 billion people – a market that no business can afford to turn down. The lure of potential new customers will only grow as China’s middle class expands (see Fig 2), with McKinsey & Company estimating that this demographic will reach 550 million by 2022. For European firms, making inroads in this market could be the difference between success and failure, particularly given the flimsy levels of economic growth predicted at home.

Developing good guanxi is essential to gaining a foothold in China. For various historical reasons, trust must be earned, usually through social connections; outsiders cannot simply walk in and expect to strike up a deal. This means that European organisations may need to work harder to forge connections in the country.

“Showing respect for Chinese connections, and evidencing that the firm in question is taking the market seriously, is crucial,” Llanwarne said. “Face-to-face engagement is also critical, which generally means making an investment into regular trips to the country to meet with business contacts.”

For successful European businesses, the rewards are likely to be enormous. Aside from the purely financial benefits, China is taking a leading role in many technological fields, including 5G solutions, mobile payments and artificial intelligence. Engaging with these developments will undoubtedly help western firms provide better products and services to their customers, both at home and abroad.

Even with an appreciation of guanxi’s finer points, it won’t be easy for European corporations to acquire market share in China. That said, China is opening up to the world in ways that would have been unimaginable a few decades ago. The recent tit-for-tat trade war between the US and China may have disrupted this somewhat, but the overall trend is still towards a more open world and a more engaged China.

“On a positive note, you don’t have to be Chinese to have guanxi in China,” Barton said. “European businesspeople can build it by spending time with Chinese partners and customers. Be prepared to invest heavily in socialising in particular – given the country’s strong food culture, time spent eating and drinking together is invaluable. This said, building guanxi from scratch is a bigger challenge and a longer-term process for a European entrepreneur. And no matter how good your guanxi is, you’ll always be an outsider in China – and growing tensions between China and the West may well exacerbate this.”

Being an outsider is not always a bad thing, though: gaining access to the business environment in China while maintaining some distance from it can be a good way for European firms to assert that some of their values are non-negotiable. It may also place greater pressure on China to tackle its reform deficit. Greater interactions between different organisations are the most likely way of creating an effective cultural synthesis – a hybrid method of business that combines the best elements of guanxi with the most rewarding aspects of western traditions.