Management consultancy, despite being a relatively new industry, has done pretty well for itself. Although the sector has its roots in the late 19th century, it really began to take off in the 1980s with the expansion of the Big Three consulting firms: McKinsey & Company, Boston Consulting Group and Bain & Company. Later, the so-called Big Four accounting firms – Deloitte, KPMG, PricewaterhouseCoopers and Ernst & Young – moved into the consulting space, and today this represents an increasingly large part of their output.

Although management consulting has experienced enviable growth, it has not fared equally well in all markets, nor has it been able to avoid setbacks along the way. In some corporate cultures, turning to consultants for support is a well-established practice, but this is not the case in others and it doesn’t seem to have adversely affected the success of their domestic businesses. Meanwhile, even the most experienced consultancy firms have faced recent claims of wrongdoing, damaging the reputation of the broader industry.

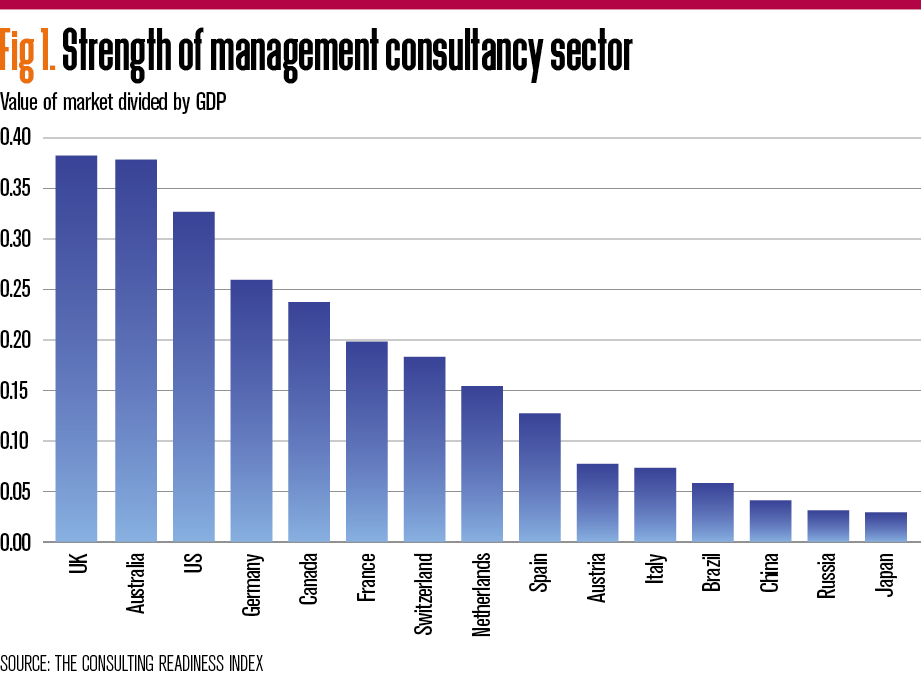

There is a significant discrepancy between the size and strength of the management consulting industry across various markets

Setbacks like these won’t send the industry into existential crisis, but consultancy firms must assess why they remain underused in some markets and how they can bolster their popularity in the countries where they are deployed. After all, management consultants are not cheap, and so they must continue to justify their fees.

Earning their crust

When discussing management consultants, it’s important to first establish what exactly they do. It’s something that individuals outside the corporate bubble may have a particular interest in – especially once they see how much consultancy firms are charging.

Though company fee structures are not disclosed, the industry leaders collect enough in total revenue to start graduate consultants on base salaries in excess of $85,000 (€78,240). According to procurement intelligence firm Beroe, the global management consultancy industry will be worth $295bn (€271.54bn) by the end of this year.

In return for these significant fees, management consultants deliver a variety of services. In the broadest possible terms, they help improve an organisation’s performance, but because each client has different strengths and weaknesses, this could involve a multitude of different processes and policies.

“Management consultants deliver value in a variety of ways,” Roy Williams, CEO of consultancy firm Vendigital, told European CEO. “Niche players are often able to drill deeper to uncover opportunities to drive measurable results by introducing cost strategies or harnessing the power of previously unrealised data insights. Using industry expertise to develop hypotheses and data science to interrogate big data in a way not previously possible has given consultants and management teams ways of looking into their businesses through lenses not previously available. Consultancies with both the data skills and implementation skills will deliver real value.”

This value is delivered in ways that extend beyond simply offering advice. Consultants may provide more concrete information in the form of data and analysis, which can help the client better assess their market position and how it can be improved upon. Expertise gained from previous projects – McKinsey has the knowledge of more than 27,000 employees to draw from – can also prove invaluable. Crucially, consultants build on the insight they provide, delivering clients with a clear roadmap for how to implement their suggested changes.

While there are plenty of jokes about management consultants not being worth the money they charge, many within the industry no longer take such comments seriously, assured of the value of their work. After all, the Big Three and Four post annual revenues that reach billions of dollars, and have done so for a number of years. If they were taking their clients for a ride, somebody probably would have noticed by now. Plus, many firms now operate a payment system that means conning clients is not really possible.

“Management consultancies are moving away from the hourly billing model to a more client-friendly and value-for-money version of billing for the total project cost,” Adam Goddard, Senior Vice President for Agencies and Consultancies at Savanta, an insight specialist firm, explained.

Alternatively, many of the larger consultancy firms will start their relationship with a client by declaring that they foresee an opportunity to boost their revenues by a particular amount. They only receive payment when, and if, they achieve their stated aim. Other consultants may agree to take a share of a client’s equity as payment, which is then sold when they file for an initial public offering. In reality, it seems that management consultancy is a little easier on client purse strings than the jokes make out.

Not for everyone

If the perception of management consultants as money sinks is unfair, then there must be another reason why some countries are not so keen on the industry. Currently, a handful of markets dominate the sector: according to data compiled by Source Global Research, the US accounts for more than half of the industry’s total revenue. Add in the UK, Germany, France, Australia, China and Canada, and you have 75 percent of the market accounted for.

Rob Walker, a partner at Ernst & Young, told European CEO that although a few countries do dominate consultancy, there were pockets of excellence to be found in many smaller markets: “Each country has its own strengths and regulations – in Germany, for example, a lot of consultancy work is focused around manufacturing. Elsewhere – in Greece, for example – there are some of the best data analytics professionals that exist in Europe because universities in the country have such a strong focus on maths. As a result, they produce some of the highest-qualified mathematical and analytical people that exist in the world.”

According to the International Council of Management Consulting Institutes’ Consulting Readiness Index, there is a significant discrepancy between the size and strength of the management consulting industry across various markets. In the latter’s case, both GDP-based and population-based assessments were carried out to determine which countries had stronger management consultancy sectors. The index discovered that anglophone countries – the UK, Australia and the US – performed well in terms of industry strength, with markets like Italy, China, Russia and Japan posting much lower figures than one might expect given each country’s economic development (see Fig 1).

Why these regional discrepancies exist is difficult to determine, but cultural factors could certainly play a part. In Italy, for example, there is a strong tradition of seeking family support in times of difficulty, which may account for a reticence to seek advice from external consultancy firms. It has also been suggested that religion might play a role, with the Protestant part of Europe having higher levels of consultancy development than those found in Southern Europe. Other explanations have been proposed, but whatever the exact cause, the uneven spread of consultancy firms shows that there remains a great deal of potential growth for the industry to pursue.

Cleaning up their act

For some of consultancy’s heavy hitters, however, attracting new clients will rely on them cleaning up their image. The industry is no stranger to controversy, with insider trading and conflicts of interest being common issues.

Last year, McKinsey faced accusations that its bankruptcy work presented a conflict of interest because its investment affiliate, McKinsey Investment Office, stood to benefit from backing securities related to the same bankruptcies that McKinsey was involved with. While the company maintains that the allegations were “wrong”, the scandal followed a number of other unpleasant claims made against the firm over the past few years: in 2016, McKinsey was implicated in a corruption scandal in South Africa. It has since apologised for its role in the incident. Going further back, a former managing partner was convicted of insider trading after leaving the firm in 2012.

Although the majority of consulting projects are completed without any suggestion of wrongdoing, consultants are privy to a great deal of sensitive information that comes with its own temptations. Consultants also have a responsibility to encourage good business practices – something that can be complicated when it means making difficult decisions and upending current ways of working.

“Private equity firms are still getting the same old story pumped through to them from consultants: all good news, zero negativity,” Goddard said. “This could mean that management consultancies are worried that if they present even a slightly negative outcome for a project, they may upset their client and potentially lose business. There is a need for greater transparency of data, including both data sources and findings, with the client. Alongside this, there is a need for impartiality – a requirement to temper the sentiment of the data.”

For consultants looking to avoid the reputational damage that has befallen some of their loftier peers, transparency – as Goddard said – is certainly important, but so too is responsibility. If a client’s business looks suspicious, then questions need to be asked. It is not enough for consultancy firms to simply claim they were not aware of any wrongdoing – not when they have the resources to help clean up the corporate environment.

The management consultancy industry is no stranger to controversy, with insider trading and conflicts of interest being common issues

Do as I say, not as I do

Outright scandals are not the only challenges facing the consultancy sector: firms have also been accused of not practising what they preach. It has become an almost universally adopted corporate mantra that diversity equals success, with the idea being that when teams are made up of a broad spectrum of individuals, comprising different races, genders and socioeconomic backgrounds, they are less rigid and more creative. In fact, McKinsey found that businesses in the top quartile for gender diversity are 21 percent more likely to post above-average profitability than firms in the bottom quartile.

However, while consulting firms are happy to peddle this advice, a closer look at their own employment habits reveals that they are not so happy to follow it themselves. In the UK, the largest consultancies have significant discrepancies between the wages they pay their male and female staff, with Bain posting a pay gap of 36 percent and Boston Consulting Group 35 percent across 2018.

When confronted with these figures, consultancy firms are quick to point out that men and women are paid equally when performing the same role; unequal figures stem from the fact that there are fewer women in senior positions. This is something that consultancies have to work harder to address. Whether it’s due to cultural factors or inflexible working practices, more needs to be done to place women in highly paid C-suite roles – if the likes of McKinsey are correct about profitability, then it’s in companies’ best interests.

Consultants could also do with listening to their own advice when it comes to new technology. Digital transformation is a core focus area for many consultancy firms, providing an obvious, although not necessarily simple, way for their clients to improve reliability, efficiency and profit.

“People have been talking about what technology allows you to do in terms of back-office transformation for a long time… About a wave of automation and robotics,” Walker said. “Now, we’re actually beginning to see this happen at real scale; the technology is now well enough understood that you can derive huge amounts of savings from automating those back-office functions. I think there are some really interesting dynamics at play in terms of the next wave of digital back-office transformation where you have more automation.”

But digitalisation is set to impact all industries, and consultancy is certainly not immune. According to data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics, which has been analysed by Consultancy.org, management consultants are among the 20 occupations most at risk from automation, with 27.1 percent facing this outcome. This does not mean that jobs will necessarily be lost, but they will certainly be changed – management consultants must prepare for this now.

Opportunity arises

Though the consultancy sector faces various challenges, there are also opportunities to be found. China’s business sector has been open to outside assistance for some time now, but years of economic isolation under the rule of Mao Zedong and the very hands-on role the state continues to play in business affairs mean many state-owned enterprises in the country are in need of reform. Consultancies from outside the country are therefore presented with a hugely lucrative market that could benefit from their services.

However, heightened tensions between China and the US of late have made things difficult for some of the industry’s major players. Subsequently, European consultancies may find their services in greater demand in the country, particularly for any projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s flagship infrastructure programme. Even so, Walker believes that consultancy firms should take some time before rushing into the Chinese market.

“The breakdown in relations between the US and China has certainly created a potential opening for consultancy firms in Europe, but they still have to proceed with caution,” Walker advised. “If you want to be successful as a consultant in China, you need to have a local partnership. At Ernst & Young, we are a global practice – we are the largest of the Big Four in China – and we have access to some really talented people who have grown up in China and know the market and its dynamics. So I think there will be opportunities, but I also think there are much more attractive opportunities than trying to dive into China.”

For consultancies that don’t have the resources or experience to venture into the Chinese market, there are other openings closer to home. In Europe, the ongoing issue of Brexit will create a huge demand for consultants on both sides of the Channel as firms look to ensure that they are operating in line with any regulatory changes.

“The outlook is positive for management consultancies across Europe, as long as they continue to focus on accountability and delivering measurable results,” Williams said. “Companies need and want to become more data-centric, and management consultancies are well placed to catalyse these corporate transformations to deliver the associated performance improvement.”

One unexpected hurdle that organisations may struggle to deal with is any economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. During a recession, cutting consultants loose may be one of the first savings that businesses choose to make. Conversely, however, one of the core capabilities that many management consultancies deliver is risk management and business continuity. As the dust begins to settle on the pandemic, more organisations may wonder why they were not better prepared for the crisis. At that point, management consultants will be ready and willing to provide the answer – for a fee, of course.