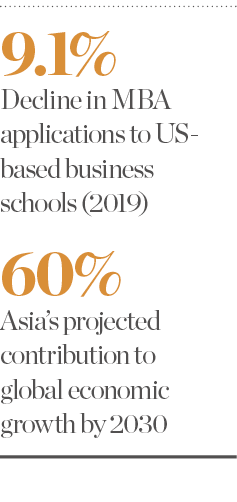

An MBA is one of the most coveted accolades in the professional world. And yet, across the globe, demand for this prestigious degree appears to be waning. According to the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC), applications to business schools saw a 3.1 percent year-on-year drop in 2019. In the US – the birthplace of the MBA – applications were down 9.1 percent.

If we look to Asia, however, we see a very different story. The GMAC reported that growth in the number of MBA applications to business schools in Asia had outstripped the rest of the world for the second consecutive year. The GMAC largely attributed this to domestic growth, with “more candidates opting to stay close to home”.

There are several other reasons why Asian students may be choosing to learn in their home countries rather than going abroad, with one possible explanation being US President Donald Trump’s divisive rhetoric, which may be dissuading potential students from applying to study overseas.

As business booms in countries like China, companies are finding themselves in urgent need of highly skilled managers

But more broadly, the trend is indicative of the wider economic shift towards Asia: as business booms in countries like China, companies are finding themselves in urgent need of highly skilled managers. At the same time, business executives are increasingly looking to Asia with a mind to capitalising on the opportunities in its rapidly growing economies.

Climbing the ranks

Business education is still relatively new in Asia. Whereas business schools have existed in the US since 1881, the first in China – the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai – was only founded in 1994. Initially, business schools in Asia struggled to make it into the international rankings: when the Financial Times’ Global MBA Ranking was introduced more than 20 years ago, there were no Asian schools listed. Today, there are 18 in the top 100, and four breaking into the top 20.

One of those to have regularly made it into the top 20 is the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) Business School. Its MBA programme has made the cut for 13 consecutive years, while its Kellogg-HKUST Executive MBA has been ranked number one in the world seven times over the past decade. This is made all the more impressive by the fact it was only established in 1991.

The high quality of business schools in Asia relative to their age is the result of growing prosperity in the region and a deeply entrenched cultural belief in the value of education. Following the Second World War, South Korea, Japan and Singapore acknowledged the value of education to their respective recoveries, and used it to rapidly industrialise their economies.

In the case of Hong Kong, the city-state’s strong international ties give it an advantage. “At the HKUST Business School, we have a highly international faculty mix,” Kar Yan Tam, Dean of HKUST Business School, told European CEO. “Our student body, including both undergraduates and postgraduates, represents more than 40 nationalities and regions.”

Formed much later than their western counterparts, Asian business schools have embraced a more modern approach from the outset. HKUST, for example, prides itself on the cutting-edge content of its business courses. “By choosing to study business at top-tier Asian universities like HKUST, students can acquire the latest and most market-relevant business knowledge,” Tam said.

A growth market

One of the main reasons for the surge in applications to Asian business schools is the economic climate. Asia is expected to be the world’s biggest driver of economic growth in the coming decades, contributing 60 percent of global growth by 2030, according to estimates published by the Asian Development Bank.

McKinsey & Company, meanwhile, found that Asia’s share of the world’s 5,000 largest firms was 43 percent in 2017, up from 36 percent in 1997. At the same time, Asia’s share of the top-performing firms globally has increased from 19 percent to 30 percent over the past 20 years. Businesspeople are increasingly interested in an education that will teach them how to capitalise on the region’s many opportunities.

“HKUST is ideally positioned in Hong Kong – a gateway to the burgeoning [Chinese] market,” Tam said. “With its established and sound legal system, Hong Kong remains a preferred location for a lot of international and mainland firms, thus presenting ongoing job opportunities for our graduates, as well as a favourable ground for innovative entrepreneurs.”

With economic power shifting to the East, it makes sense that more businesspeople would choose to consolidate their careers there. Lawrence Linker, founder of MBA Link in Singapore, told the Financial Times that more entrepreneurs are interested in establishing their businesses in Asia, rather than simply taking their learning back to the US, as was more commonplace several decades ago.

At the same time, Asian companies are becoming more welcoming of international employees. In 2018, Japan announced it would bring in 340,000 foreign workers to take both high-skilled and low-wage jobs over the next five years. This represented a major shift for a country where foreign residents make up just two percent of the population.

David Hackett, Director of McGill University’s MBA Japan programme – the first Canadian degree programme offered in Japan – agrees that international students are becoming more valuable to the Japanese market. He told European CEO: “CEOs and HR directors all tell me one of their greatest challenges is finding well-trained, motivated talent that can work in a global environment.”

That something special

Another reason why Asian business schools are enjoying a surge in applicants is that they place a strong focus on the science and technology sectors. Many believe more general MBAs are losing their appeal, as specialised tech roles become highly valued in the job market. Asian business schools have not underestimated the importance of specialist courses.

“HKUST presents a combined strength of technology and business education,” Tam told European CEO. “We work closely with our engineering school and science school to offer a number of electives – for example, on big data and data analytics – and joint programmes like [our] MSc in fintech and BSc in biotech and business to nurture the next generation of cross-disciplinary talent, which is increasingly important in the new technology-driven economy.”

This focus on specialisation, combined with an increasing demand for management positions in Asian companies, can result in an enviable premium for MBA graduates. Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Antai College of Economics and Management delivered a 201 percent average pay increase for MBA graduates in 2019, whereas an MBA from Harvard Business School increased salaries by 110 percent.

It is worth pointing out that, at nine percent, the decline in MBA applications to US business schools is relatively small. Nonetheless, it signals the dawn of a new era in business education. Until recently, the US was the most sought-after country for prospective MBA students because its position as the world’s largest economy was undisputed. Now, as Asia becomes the economic growth engine of the world, we can expect business education to shift to the East.