The world of fashion moves quickly: what is in vogue one week is destined for the trash heap the next, while glossy magazines fill their pages by shaming celebrities who have been spotted wearing an item of clothing more than once. This is good news for fashion designers, but bad news for the planet.

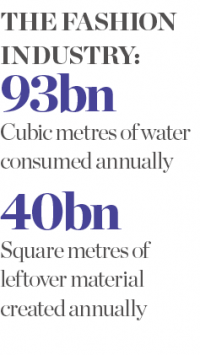

The UN Conference on Trade and Development considers the fashion industry to be the second-most polluting in the world, responsible for the consumption of 93 billion cubic metres of water every year – enough to meet the needs of five million people. Perhaps more damaging is the sheer amount of waste that the industry produces, much of which ends up in landfill or the oceans.

For the trashion trend to really make an impact, the wider fashion market needs to take part

Ultimately, the best way to reduce the sector’s environmental impact is for us all to purchase less, but it’s difficult to determine what the ‘right’ number of shoes or trousers or dresses is. As such, some designers and fashion brands have been working to ensure that the garments we do buy are less damaging to the planet. One trend that has emerged is ‘trashion’.

Distinct from upcycling, where an item that is past its best is given a new lease of life, trashion takes things that have been discarded and turns them into new garments. This can be done to make an artistic statement about pollution, but sometimes it is simply a way of creating unique items of clothing in a world where so much of fashion is derivative. Whatever the reason, it is in the planet’s best interests for the trashion trend to catch on.

Waste not, want not

Australian artist Marina DeBris is one of the longest-standing adherents of the trashion movement. Since 2009, she has been creating art from the waste she collects, hoping that her work prompts viewers to question the need for single-use items. “My inspiration came when I moved from Bondi Beach, Australia to Venice Beach, California,” DeBris told European CEO. “I immediately noticed a significant amount of waste washing up on the beaches. As I became more involved with ocean advocacy groups like Heal the Bay, 5 Gyres and Algalita, I began to realise that it was doing more than just being ugly. It was causing so much harm to marine life.”

Among DeBris’ works are a ‘ball gown’ made entirely of discarded balls found on local beaches, a kilt made of crisp packets and many pieces crafted from old netting, takeaway boxes and countless other waste items. In addition to her artwork, DeBris is also an advocate for environmental policies that would reduce the amount of waste that ends up contaminating the natural environment.

“The trashion collection has garnered considerable attention, especially when pieces are worn in live performances,” DeBris said. “I think that is partly because fashion is visually exciting, but also because most of us wear clothes. When the audience gets a close look at the materials I use, that sparks interest and a dialogue.”

DeBris is not the only artist hoping to start a conversation about the impact the fashion industry is having on the planet. Irish artist Áinne Burke recently created four garments out of litter collected by street sweepers in London, which were displayed earlier this year during an exhibition at Imperial College London. Although the art world appears to be setting the trend, designers that are more directly associated with the world of mainstream fashion are also starting to join the trashion movement.

Who’s who

Daniel Silverstein, also known as Zero Waste Daniel, is a New-York-based clothing designer who turns pre-consumer waste from the fashion industry into new items of clothing to avoid sending material to landfill. While DeBris focuses on the waste that consumers throw out, Silverstein shines a spotlight on the fashion industry’s internal failings. A 2016 study by Reverse Resources found that, by optimistic estimates, the global clothing industry creates 40 billion square metres of leftover material every year – enough to cover the entire country of Estonia. Similarly, Paris-based fashion label 1/OFF seeks to connect the “past with the future, the fun with the formal, the gutter with the catwalk”.

But many trashion brands are finding that economies of scale are hard to come by. The improvised nature of clothing made from scraps or waste means that many pieces are unique and are priced accordingly. A pair of jogging bottoms designed by Silverstein and made from design-room scraps, for example, cost $99 (€91).

Fashion not only causes such damage to the environment because it is fast moving, but also because – in the developed world, at least – it is cheap. The attitude of buy, throw away and buy again needs to be challenged if fashion is to improve its sustainable credentials. However, even if trashion doesn’t provide a like-for-like replacement for high-street garments, the movement may still broaden the fashion conversation.

“Fabrice Monteiro, who created a photo project titled The Prophecy, is an artist I admire,” DeBris said. “It’s a striking photographic series where he works with artists to create scenes that reflect modern man’s treatment of the environment. Similarly, photographer Chris Jordan created a photo series called Albatross, which depicts the contents of the stomachs of [albatrosses that have] died from ingesting plastic. This series, in particular, was a major inspiration for my work.”

Like DeBris’ own pieces, art that highlights the wasteful culture that has been allowed to dominate the economy, not just the fashion industry, will help push society in a greener direction.

Starting a craze

For the trashion trend to really make an impact, the wider fashion market needs to take part. DeBris thinks that things are improving, particularly in terms of the conscious decisions that designers, manufacturers and consumers are making. “Although I’m not in the fashion industry itself, I have seen a lot more interest in people knowing where their clothes were made, how they were made and what materials are used,” DeBris explained. “For instance, thrift store clothing, clothes swaps and clothes libraries have become much more mainstream and accessible. Designers are producing clothing with more sustainable fabrics and many are now addressing the issue of waste and recycling or reusing materials.”

In addition to 1/OFF, other sustainable fashion brands are cropping up. South African company Sealand Gear turns unwanted yacht sails and canvas tents into backpacks and coats, and UK jeweller Lylie’s recycles the discarded metal from electronic or dental waste to create designer pieces. But while boutique designers are joining the trend, better-known brands don’t seem so keen. Prada did launch its Re-Nylon range last year as part of the company’s ambition to only use repurposed nylon by 2021, but most fashion firms remain content to source new materials for now.

Of course, designers and brands can only do so much: consumers must also push the fashion industry towards greater levels of sustainability. The trashion movement highlights how important it is that clothing manufacturers source and responsibly dispose of their materials, but shoppers need to buy responsibly too. Ultimately, that might mean

choosing not to buy at all.