The European Banking Authority (EBA) has taken umbrage to British bankers’ allowances, based on what it sees as a blatant disregard for new EU rules on bank bonuses. According to a recent investigation across the 28 EU member states, the regulatory agency has reported that 39 financial institutions, among them Barclays, RBS and HSBC, use so-called ‘role-based’ or ‘market value’ allowances, which they claim to be forms of fixed remuneration. However, after further inspection, and to the frustration of the EBA, it has become clear that in most cases the institutions have used these allowances as a way of circumventing EU regulations, rendering the EU bonus cap ineffective. This is because role-based allowances, while claimed as fixed pay, can be raised or lowered annually and are non-pensionable in nature, so can function like bonuses.

London’s financial services sector is staggering in size. It makes a healthy contribution to the UK’s overall economy and boasts long-standing political ties with the incumbent Conservative government. These ties have seen Chancellor George Osborne launch a legal challenge to both the bonus cap and an EU financial transactions tax. For these reasons, it is equally unsurprising and understandable that UK authorities have opted to back British banks’ use of role-based allowances. The payment strategy used by the banks creates a clever halfway house, acting as neither basic nor bonus pay, and is devised in such a way as to subvert the regulations emanating from Brussels.

Clamping down

Details about the bonus limitations, which are designed to place a constraint on the ratio between variable and fixed pay, are enshrined in law by the EU Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV), and can be found under Article 94(1)(g) of the legislation. In it, a clear distinction is made between fixed and variable rates of pay. In the opinion of the EBA, fixed (more commonly known as basic) salary should be reflective of an individual’s professional experience and responsibilities within the company, as laid out in their job description. Variable pay (bonuses) should be linked to performance or other elements that do not fall within the remit of an employee’s regular workload. It all appears rather self-explanatory, except for the fact that CRD IV stipulates that variable pay “shall not exceed 100 percent of the fixed component of the total remuneration (200 percent with shareholders’ approval)”. This provision forms the primary source of contention for bankers and the financial institutions they work for.

Adding to the annoyance of those within the industry, the EBA has stated that, in order for banks to comply with the CRD IV bonus cap, role-based allowances must be “predetermined, transparent to staff, permanent (i.e. maintained over time and tied to specific role and organisational responsibilities), not provide incentives to take risks, and (without prejudice to national law) be non-revocable”. Naturally, the banks’ methods of remuneration fail to meet the mark on every point. Brussels is not pleased about this but, for now at least, it is merely expressing its discontent in the hope that UK authorities will do the dirty work – giving them until December 31 2014 to bring institutions to heel.

In the meantime, the EBA will be revising its guidelines on remuneration policies and practices, which will be finalised at some point in the middle of next year. This will update the existing rules and make role-based allowances officially in breach of EU regulations. Until then, Brussels will continue being frustrated by British banks’ defiance, while financial institutions will have to put their thinking caps on in order to come up with another means of sidestepping the rules in time for next year.

Refusing to accept

Barclays’ position is that the bank, despite the EBA’s opinion, will continue its tradition of paying staff performance-related pay: “Barclays remains committed to paying competitively and paying for performance” stated a spokesperson. And if Brussels has rested its hope on compliance being aided by UK regulators, then it is very sadly mistaken. At the City Banquet in London, one day after the EBA gave its judgment on the matter of curbing the Square Mile’s bonus culture, the Bank of England’s Deputy Governor and Chief Executive of the Prudential Regulation Authority, Andrew Bailey, labelled the EU cap on bankers’ bonuses as bad policy. “Sadly, taking this stance sometimes attracts the criticism of being pro-bonuses”, he added.

Non-monetary motivators

Four studies that prove there are other ways to increase performance and productivity:

Man’s search for meaning: the case of Legos (Ariely, Kamenica, Prelec)

Productivity increases when employees see the fruits of their labour

This study saw participants constructing Lego Bionicles models

The IKEA effect (Norton, Mochon, Ariely)

Employees take more pride in completing the project the more difficult it is

This study involved making origami figures with and without instructions

It’s not all about me (Grant, Hofmann)

Employees follow rules more carefully when they are connected with helping others

This study observed that ‘Wash Your Hands’ signs were more effective when they mentioned protecting patients

The power of kawaii (Nittono, Fukushima, Yano, Moriya)

Employees focus better when exposed to images that trigger positive emotions

This study used Japanese ‘kawaii’ images of cute cartoon animals, placed strategically in offices

There is some logic behind Bailey’s and others’ opposition to the cap. A very real cause for concern is that if restrictions are applied too rigorously in Europe, then top talent will be lured away to jurisdictions where such sanctions do not apply. Furthermore, the stipulations around bonuses also risk causing harm to financial institutions, with the rules making it harder to adjust capital levels on the off chance that the markets take a turn for the worse. However, there is a deeper-rooted reason for the City’s sentiments, which forms the very bedrock of not just the financial world, but also our society at large and one that is at the very heart of our capitalist culture.

There is an illusion around banking, influenced by popular culture, that it is a world of fast cars and lavish parties. While there is certainly a lot of money in the profession, a lot has changed since the 1980s and 90s, most of all the financial crash of 2008 which brought with it tighter rules and increased amounts of red tape. The duller and lesser-publicised part of the industry is how such wealth is created; through a huge amount of hard work and very, very long hours. There are reasons why a junior analyst averages £35,000. Firstly, they work for every penny of that inflated graduate salary. Secondly, financial institutions make a lot of money and, therefore, have the means to pay their employees a higher level of pay, and lastly, because the workers deserve it. All those involved play an important part in the process of wealth creation, so why shouldn’t they share in the profits? These lines of argument will be familiar to most, with the same types of conversations occurring over the weekly wages of top-flight footballers, who make more in a month than many hope to achieve over the course of their working lives. There is, however, another justification for this considerable rate of compensation and it comes down to one thing – motivation.

Performing for cash

Banks clearly believe that in order to get the best out of their staff they must pay for performance, and pay well, with the big four in the UK setting aside large bonus pools for their top players. In 2012, Barclays, HSBC, RBS and Lloyds handed out over £5.1bn. While that figure alone is pretty staggering, one would like to think that the bonuses were justified by the amount of profit that was made as a result of hard work and dedication. After all, big banks pay for performance – right? Well that is true of Barclays and HSBC, who made profits of £7bn and £13.7bn respectively, paying out £1.8bn and £2.4bn to their staff.

However, the same cannot be said of RBS and Lloyds, both of whom made massive losses, but still managed find £607m (RBS) and £375m (Lloyds) spare for their best and brightest. This begs the question: is money an effective tool for motivating people?

For better or worse, humans have come a long way in a relatively short space of time, conquering the environment and bending their surroundings to their will in order to better satisfy their needs. According to clinical psychologist Frederick Herzberg, such needs can be broken into two fundamental groups, which he labelled ‘hygiene’, or ‘animal’ needs; and ‘self-development’, or ‘motivational’ needs. Animal needs consist of food, water and shelter, providing protection from the elements and potential predators. Once these basic requirements have been met human beings begin to be motivated by desires for self-development.

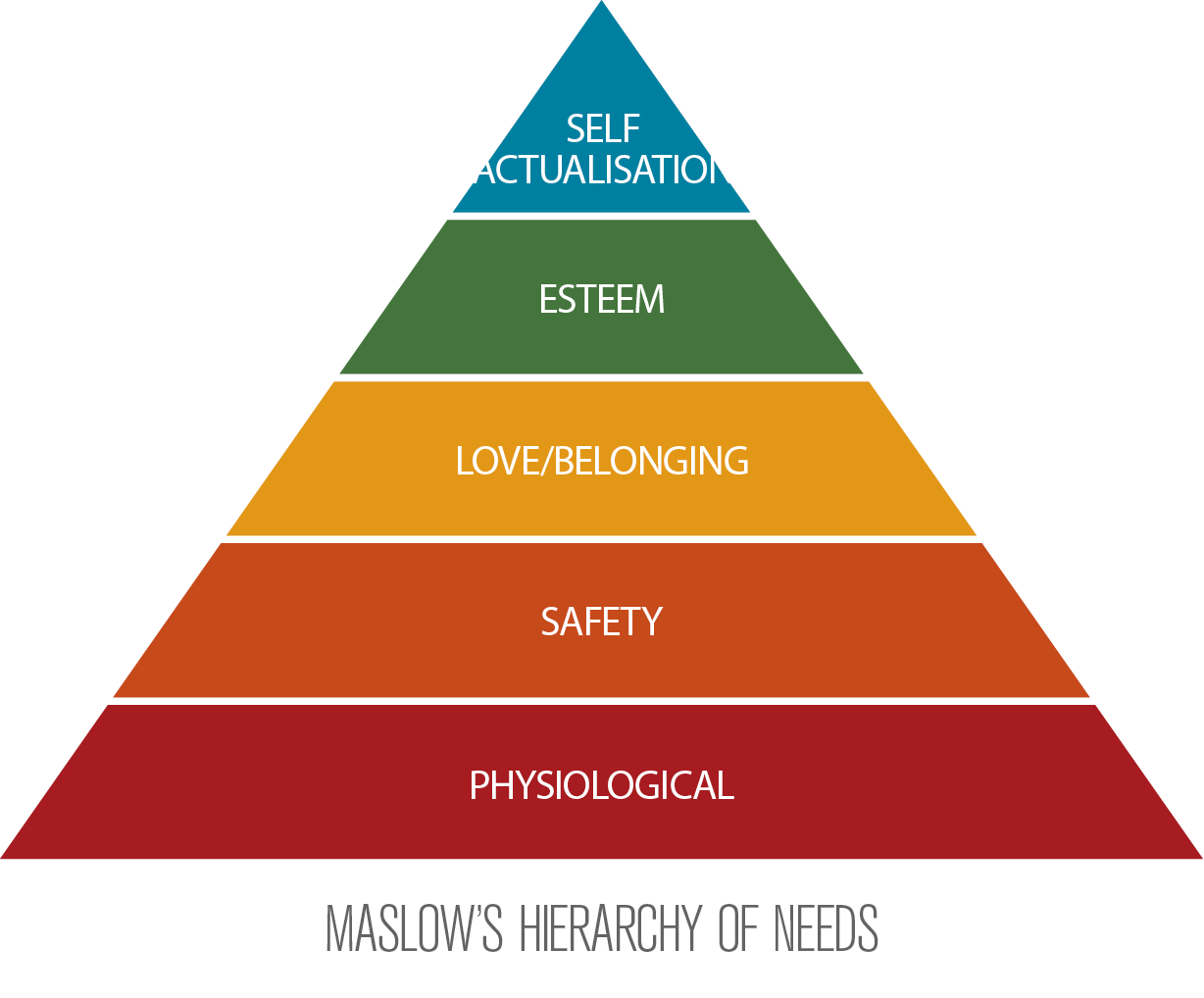

Parallels to Herzberg’s assumptions are apparent in work done by fellow psychologist, Abraham Maslow. Those familiar with his work will be aware that he is responsible for creating the ‘hierarchy of needs’. He, like others in his field, was obsessed with figuring out what motivated people to do the things they do. His hierarchy of needs develops Herzberg’s ideas, dividing needs in to five different sections: physiological (food, water, shelter, warmth, reproduction, sleep); safety (security, order, law, stability, freedom from fear); belonging and love (friendship, intimacy, affection and love); esteem (achievement, mastery, independence, status, dominance, prestige, respect); and self-actualisation (realising personal potential, self-fulfilment, personal growth). The idea being that, as each motivational stage is fulfilled, the individual progresses to the next phase, ending in the highest stage: self-actualisation.

There are some things money can’t buy

What does this have to do with understanding the effectiveness of money as a motivator? Well, everything. In management researcher Daniel Pink’s talk at the RSA a few years ago, he spoke about two incredibly intriguing studies that call into question the success of money as a tool for getting people to get things done. He explained how one study, conducted at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), involved a group of students who were presented with various types of tasks that they were expected to complete. These ranged from cognitive challenges, such as memory tests and puzzle completion, to rudimentary physical tasks, like throwing a ball through a hoop. To spice things up a little bit, participants were incentivised. They were presented with three different levels of monetary rewards based on how well they performed in the numerous tasks.

Traditional methods of thinking, especially those held by the likes of Barclays, would suggest that the added incentive of performance-based pay would be lead to improved overall performance and is one of the prime justifications for bankers’ bonuses. The results of the MIT study, however, produce some intriguing conclusions that contradict the banks’ long-held beliefs. After analysing the scores, the test showed that, as long as the » task involved basic mechanical skills (akin to factory line work) then financial reward followed traditional expectations – the bigger the bonus, the better the individual performed. However, when the task required even the slightest amount of cognitive skill, the results changed drastically, with the larger reward leading to participants’ scores dropping through the floor. Pink explains that this result goes against practically everything that most university students learn about economics – that the greater the incentive, the more of a particular behaviour can be expected.

What the test reveals is that once a task moves into the realm of requiring cognitive ability, higher monetary rewards can lead to poorer performance. To prove that this wasn’t a fluke, the study was replicated in other parts of the globe. Pink continued by telling the story of how they conducted the study in Madurai, a place located in rural India, where the monetary reward that was used to incentivise MIT students equates to a considerable sum of money. Here, participants who performed relatively well received the equivalent of two weeks salary, those that did moderately well were given one month’s salary, and finally, the highest performers got a bonus worth two months of their basic income. The sums of money involved, in proportion to their average yearly income, were comparable to those of bankers bonuses and served as the perfect insight in to the efficacy of performance related pay championed by senior members within the financial services sector. In India, the people that were given the medium reward did no better than those offered the smaller amount of money, but interestingly, those that were offered the highest amount of money did worst out of all the participants. Their scores were the lowest of the lot.

How much is enough?

Studies like these have been replicated all over the world, producing the same result every single time. They highlight that for simple tasks, where mechanical skill is required, money works as a great tool for incentivising your work force to perform better and improve overall productivity. But as soon as you start using money to try and improve individual performance in tasks that require cognitive functions, such as those needed by bankers, higher amounts of pay cause performance to suffer dramatically. It becomes hard to dismiss these findings when considering that at the time of the financial crisis there were astronomical sums of cash incentives flying around and there was a simultaneous peak in reckless behaviour. Poor decisions were being made at every turn and the actions of many within the industry nearly led to a complete economic and social collapse.

That is not to say that bankers should be denied bonuses all together. The EBA recognises this, hence the clause in the new regulations that stipulates that variable pay shall not exceed 100 percent of the fixed component of the total remuneration (200 percent with shareholders’ approval). Being able to pay 200 percent of someone’s basic salary in the form of a bonus is still a significant amount of money and to scoff at it does little to improve the sector’s tarnished public image. While it is true that setting limitations on private businesses choices is contrary to the principles of a free capitalist society, the fact remains that banks jeopardised the stability of the entire system as a result of their actions. In order to win back the public’s trust, banks must be willing to endure certain policies that they and their sympathisers deem extreme in nature.

Even if banks were to back down, rolling out a scheme to curb bonuses will affect the UK’s financial sector, though to what extent is still unknown. The City of London, like it or not, is the beating heart of the UK’s economy. This fact alone places domestic regulators and the government between a rock and a hard place. If it threatens to damage a UK economy that relies heavily on the wealth creation of the financial sector, favouring the move would be seen as foolish by many. Yet still, Brussels is hell-bent on enforcing the new rules, regardless of the economic consequences. While many applaud the EBA for trying to rein in bankers’ bonuses, if it leads to another recession, perhaps then people will reconsider their sentiments. At the same time, banks themselves would be well advised to reconsider the logic behind their bonus schemes. They can fight for the right to pay what they want, but whether enforcing that right leads to the desired results is clearly in question.