In the zero-sum economy of austerity Europe, where the arts are in constant competition for dwindling public funds, a lifeline from corporate investment is slowly being severed due to stockholder pressure to secure the bottom line.

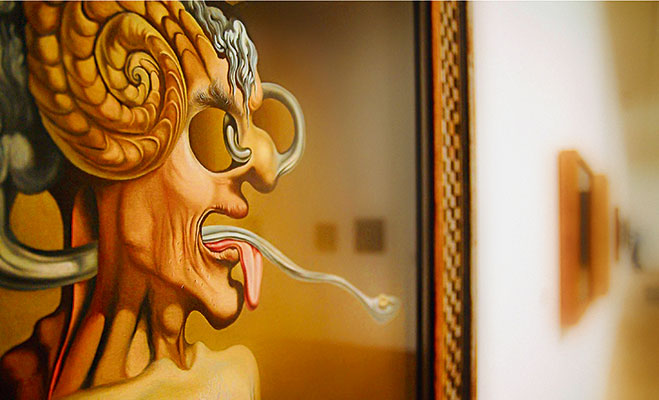

In April, a museum in Italy started burning its collection of artworks in protest at budget cuts which it says have left cultural institutions out of pocket. Antonio Manfredi, director of the Casoria Contemporary Art Museum in Naples, set fire to a painting by French artist Severine Bourguignon, who was in favour of the protest, in full view of the world’s media. “Our 1,000 artworks are headed for destruction anyway because of the indifference,” said Manfredi.

The Creative Europe programme aims to promote and safeguard cultural and linguistic diversity

Funding of the arts is, in itself, a delicate art. Despite a UK government drive to encourage philanthropy, investment by businesses has dropped to its lowest level for seven years, creating further dissatisfaction and high-drama in the sector. Down seven percent on 2010’s figures, sponsors from organisations traditionally associated with funding art projects are tightening the corporate purse as stockholder pressure increases.

According to figures released by campaigning charity Arts & Business in February, the overall trends in the UK noted a striking fall in corporate business investment in the arts for the fourth year in a row, down to £134.2m, as well as the growing gap in fortunes between London and other UK regions. The 2011 figures reveal that while most businesses are still committed to working with the arts, they are not “hard-wired” to do so. Corporate money is a discretionary spend – particularly in hard times – and consequently, business investment last year was lower than it was in 2004/05.

The Arts & Business figures also disclosed that 81 percent of all individual giving goes to investment in London, demonstrating how arts organisations further afield are being hit hardest, often facing the added blow of suffering cuts to local authority grants. While the capital saw a nine percent increase in private-sector investment to £488m, and the northwest was up three percent to £21m, almost everywhere else suffered a fall. The southwest was down 32 percent to £15m, the southeast down 14 percent to £28m, the northeast down 13 percent to £12.1m, and the Yorkshire region down 12 percent to £16.2m.

On the face of it, the numbers might seem to be disappointing for the UK’s culture secretary Jeremy Hunt, who declared 2011 “a year of corporate philanthropy”, but staying true to the central tenet of the coalition’s arts policy, he has drawn positives from the data, as there has been an overall four percent growth in total private sector investment to £686m. Indeed, the six percent increase in private individual philanthropy and the figure for individual investment in 2010/2011, was £382.2m, higher than it has ever been. “I do believe in state funding,” he said, “but we are committed to a mixed-economy funding model for the arts. These figures are a real tribute to the determination of the cultural sector to boost its fundraising and strengthen the financial resilience of the arts organisations, especially when times are tough.”

Is Europe faring any better?

The European Commission has planned to launch the world’s largest ever cultural funding programme, with €1.8bn allocated for visual and performing arts, film, music, literature and architecture, with plans to release the money between 2014 and 2020, leveraging on private investment and attempts to shift the European mentality from grants to loans. The Creative Europe programme aims to promote and safeguard cultural and linguistic diversity and will mean a much-needed boost for Europe’s cultural and creative sectors.

Androulla Vassiliou, European Commissioner for Education, Culture Multilingualism and Youth said the programme is imperative for jobs and sustainable growth in the sector, but also to break into new, unchartered markets: “This investment will help tens of thousands of artists and cultural professionals and safeguard and promote diversity across the continent,” she said.

“The culture secretary has conceded that a more open discussion of the value of philanthropy and more transparency about individual giving will encourage others to come forward and part with their cash”

The programme has echoed organisations’ desires for European culture funding to be thrust once again into the spotlight, as austerity measures take hold. In 2010, Nicolas Sarkozy proposed making cuts at cultural institutions like the Louvre, the Palace of Versailles and the National Library – with only one worker to replace every two who retire.

The Pompidou Centre’s labour union estimated the institutions will lose some 200 jobs in the next decade as a result. Sarkozy’s stance resulted in the Pompidou museum, along with several other cultural venues, shutting down for more than two weeks as a result of strike action. In Italy, the world-famous opera house La Scala faces a shortfall of almost €7m because of reductions in subsidies. In the Netherlands and Hungary, conservative-led governments have had financing for arts programmes slashed; Portugal has abolished its Ministry of Culture.

The New York Times has commented that European policy is looking further and further to the US model of cultural investment. Journalist Michael Kimmelman believes the ‘Americanisation’ of private financing has been creeping into the continent for quite some time, and government patronage for culture is no panacea in Europe: “Private benefaction can have its distinct advantages,” he said. “True, strings are usually attached. But a variety of donors tend to allow an institution more independence and flexibility, more lightness on its feet. European cultural institutions have, compared with those in the US, next to no tradition of private giving and one consequence is Europe is stuck between privatisation and the lack of private donors.”

Erik Lundsgaarde, research fellow at the German Development Institute, believes American philanthropists have played an important role in drawing attention to giving for global development. “One priority area for engagement among European donors should be the promotion of greater transparency within the philanthropic sector through support for greater data collection efforts related to private aid provision,” he said in his 2011 paper, “Global Philanthropists and European Development Cooperation”. “This goal can be pursued in part by improving mandatory financial reporting on foundation activities and charitable giving within member states and at the EU level.”

When recalling how the Louvre relied on a gift from Total, Didier Alaime, who represents the country’s biggest union – the Confédération Générale du Travail – said: “The more public policies are dependent on private financing, the more they risk feeling the ups and downs of the market. The more we’re dependent on outside financing, the less we control the policies that are financed. It gives the impression that culture is merchandise.”

According to UK media distributor Channel 4’s cultural editor Matthew Cain, it’s highly unlikely that private investment is set to become the dominant funding force, at least not of UK culture: “The culture secretary has conceded that a more open discussion of the value of philanthropy and more transparency about individual giving will encourage others to come forward and part with their cash,” he said. “But glory or even slight recognition is often the furthest thing from the minds of UK philanthropists – a strikingly different set up from the US. Trends have shown individuals prefer to give money to bespoke projects, rather than contribute to the ongoing maintenance of an institution. It is a huge pitfall to rely too heavily on (the offerings of) individuals whose wealth might fluctuate in line with the economy.”

Pressure on the purse

International tobacco product manufacturer JTI declined to comment on any changes to its investment portfolio, but continues to support a number of renowned cultural institutions worldwide, including the Louvre, the Prado in Madrid, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Royal Academy of Arts and the Teatro alla Scala Museum in Milan. The company also supports the Moscow Easter Festival and Stars of the White Nights Festival in St. Petersburg, has a long-term partnership with the Mariinsky Theatre in Russia, while continuing to partner the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, the Hermitage and the world-famous Bolshoi Theatre.

Rather than invest solely in one major exhibition, PricewaterhouseCoopers is increasing the amount of time its staff give supporting community arts projects that engage with disaffected young people, rather than invest a predetermined amount. David Adair, Head of Community Affairs, said: “We continue to support the Our Theatre programme with Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, at the same level we have for the past 15 years, and the Unicorn’s Children’s Theatre and the Royal Exchange Theatre project in Manchester.” The company is also sponsoring a ticket scheme with the Old Vic Theatre, offering a number of discounted tickets to all under-25s.

Some corporate institutions believe that in times of austerity it’s more important than ever to support artistic and cultural programmes, rather than cut back. Rena de Sisto, Global Arts and Culture executive at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said: “Our support for arts and culture is unwavering and our global programmes have in fact grown in the past few years. And even during challenging financial times, we believe that we have a responsibility to make a positive impact on economies and societies throughout the world, as part of our corporate social responsibility efforts”.

The outlook for art funding looks mixed, and depends on global economic revival. It is widely acknowledged that in the interim, organisations must find new ways to engage with businesses and individuals, by becoming more flexible with their business model and more sophisticated and creative with their offers. However, in recent years, the partnership of private funding and arts organisations has sparked concern that marketing and public relations strategies could damage the integrity of cultural institutions. For others, it’s government restrictions that are causing problems. London-based creative production company Serious, who produce live music events, including the large-scale London Jazz Festival, have only recently established Serious Trust Limited to enable it to attract funding from individual donors in the future, in line with current UK Government policy, but director Claire Whitaker is still worried: “Unfortunately, the latest budget appears to have had a detrimental impact on donations of a significant size, which could affect Serious’ philanthropic support in the near term.”

Benefits of corporate sponsorship

However, there is evidence to suggest that the partnership of corporate sponsorship and arts is not as problematic as it might seem, and seemingly offers benefits that governmental funding cannot provide. While many government-run museums struggle under sclerotic bureaucracies, like in Italy, private collectors and companies have set up foundations and exhibition spaces like the Fondazione Prada in Milan and the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, and seem to be setting a standard for contemporary art there. In Germany, the opera house and concert hall Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, criticised for eschewing government money and relying on private patronage, has given the Bayreuth and Salzburg festivals a run for their money.

Despite lesser-known institutions outside Paris having their funding slashed, and generous subsidies being radically cut, France’s love affair with the arts is determined to outrun the recession. Cultural powerhouses like the Grand Palais remain sacrosanct and scored record ticket sales in the past few years, and nationwide, cinemas haven’t been as busy since the early 80s. Results from a 2011 report from France’s leading online technology newspaper, Le Journal du Net, indicated the largest number of investors into French art organisations came from the US.

In the UK, an anonymous private donor gave £1.5m to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, where the money will go towards the £7m needed to build the Indoor Jacobean Theatre – aimed to be the most complete recreation of an English renaissance indoor theatre. The donor has also pledged to double the contribution, providing the Globe manages to raise additional amounts by itself.

“There is no such thing as free money in the arts, there are always strings attached,” says BBC Arts editor Will Gompertz. “The government wants certain targets attained in return for investment, philanthropists need plenty of wining and dining and corporate sponsors have business goals that need to be reached, all of which the arts institutions know, having weighed up the pros and cons before taking the money.”

Former Royal Opera House chief executive Michael Kaiser believes that arts organisations must plan much further ahead if they want to attract more private sector funding, especially if investors want a say in the artistic process. Kaiser, who is now president of the Kennedy Centre in Washington in the US, said: “They need to plan three, four or five years in advance, not just a few months, to give them time to find and cultivate new donors and bring them into the picture, and also to make bigger, more exciting, and more surprising projects.

“One of the challenges in this country is that organisations – even some large ones – have typically gone to the same suspects [for donations] all the time. That also comes from doing your programme planning on too short a time frame.”

Kaiser also stresses that while it might be harder for smaller arts organisations to attract corporate funding, it was “simply not true” that fundraising from individuals was harder for small, non-national arts organisations: “Even for a theatre company that might have a turnover of £1.5m a year, one can raise substantial sums,” he said. “The mistake people make about fundraising is they think it’s about the rich. A vast majority of funding comes from the middle-class, and a large number of donors are not going to give you £1m or £50,000 or even £5,000. But they’ll give you £50 or £100 a year. It adds up. The notion that you have to rely on the super-rich and you have to be based in European capital cities is simply not true.”

Some of Britain’s most prominent philanthropists who have donated hundreds of millions of pounds to the creative industries have warned that private giving will not bridge the gap left by the cuts to state funding for the arts. Among others, Sir John Ritblat, who has given to the British Library and the Wallace Collection, and Anthony D’Offay, the art dealer who sold his private collection to the state for a fraction of its market value, wrote to David Cameron in the wake of the Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review in 2010, warning philanthropy is an addition to, not a substitute for, state funding. Julia Peyton Jones, director of the Serpentine Gallery in London, has also warned private philanthropy will not make up the government shortfall. “The question of whether corporate philanthropists will step in to fill the gap is not realistic,” she said.

Increased investment

In December 2011, BP announced it will invest almost £10m in the four partnerships with The British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the Royal Opera House and Tate Britain over the next five years, in agreements representing one of the most significant long-term corporate investments in UK arts and culture. Each of the four institutions has a long-standing partnership with the oil giant – most stretching back over 20 years – and will see the new agreements extend for a further five years, to 2017.

The Co-operative Group has announced its continued support and funding until at least 2014 to the British Youth Film Academy. The £1.2m, six year partnership aims to deliver a unique opportunity for 14-25-year-olds, providing hands-on filmmaking experience through summer camps, events and workshops.

“The plummeting investment figures reveal there remains an acute need to drive increased private investment into the arts”

Supported by a trebling of the channel’s budget, Sky Arts is set to support a number of arts projects and emerging British artists in a range of innovative projects this year. In April, the company also announced its intention to build on its commitment to original British programming with a major investment of £600m by 2014 in feature-length British films for television.

Much-needed conservation work has been undertaken on works such as Picasso’s Woman in Blue at the Reina Sofia in Madrid; one of Leonardo Da Vinci’s earliest manuscripts at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan; and pieces of Urartian jewellery at the Rezan Has Museum in Turkey, thanks to the Bank of America and Merrill Lynch.

This year, the company is sponsoring Lucian Freud Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in London and Americans in Florence, Sargent and the American Impressionists at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, as well as lending a supportive hand to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The Europe branch president of Bank of America Merrill Lynch and chair of Arts & Business leadership campaign Jonathan Moulds said: “The plummeting investment figures reveal there remains an acute need to drive increased private investment into the arts. I look forward to working alongside other business leaders to help sustain and grow the funding and development of the arts in the UK. It is through partnerships and involvement at every level that we can embed real change.”

Arts & Business believes 2012 is shaping up to be a pivotal year, with business respondents expecting investment to increase at a faster pace, although when it will be restored to pre-recession levels is not certain. “If the previous slump is anything to go by, business investment in the cultural sector should start picking up once the economic climate starts showing clear signs of improvement,” said director Philip Spedding.

Despite the gloomy predictions, cultural appetite is stronger than ever: record cinema box office figures, a buoyant West End in London and sell-out exhibitions across the continent, and an imaginative way of talking about what’s going on the world better than any government white paper. Sir Richard Eyre, the writer-director and former head of the National Theatre in the UK expressed why European culture must continue to be considered a priority: “Further cuts to organisations will result in ‘cultural apartheid,’” he said. “By diminishing the opportunity to experience the arts or to study them and the humanities – literature, philosophy, history, religion, languages – we condemn future generations to a life a little less than human.”