Everyone knows that talent is instrumental to an organisation’s success – add the brightest, most creative minds to a company and you’re onto a winner. But while employing skilled team members to innovate and produce good results is a prerequisite of success, it is equally important to avoid ill-equipped and poorly performing players. After all, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Unfortunately, however, bad hires are an all too common occurrence –to the detriment of organisations everywhere.

A faulty recruitment process is often to blame: employers who rely on instincts and assumptions, skirt around the truth during interviews and do not carry out due diligence will only be met with failure. According to Leadership IQ, a leadership training and research firm, around 46 percent of new hires fail within the first 18 months of their employment, with only 19 percent being deemed as an ‘unequivocal success’ in their new role. The impact on an organisation can be far-reaching and cost significantly more than simply the price of replacing a bad hire, which is no small sum in and of itself.

Prepare to fail

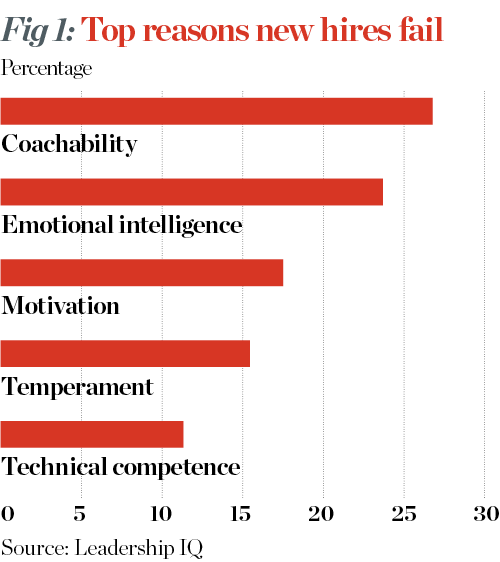

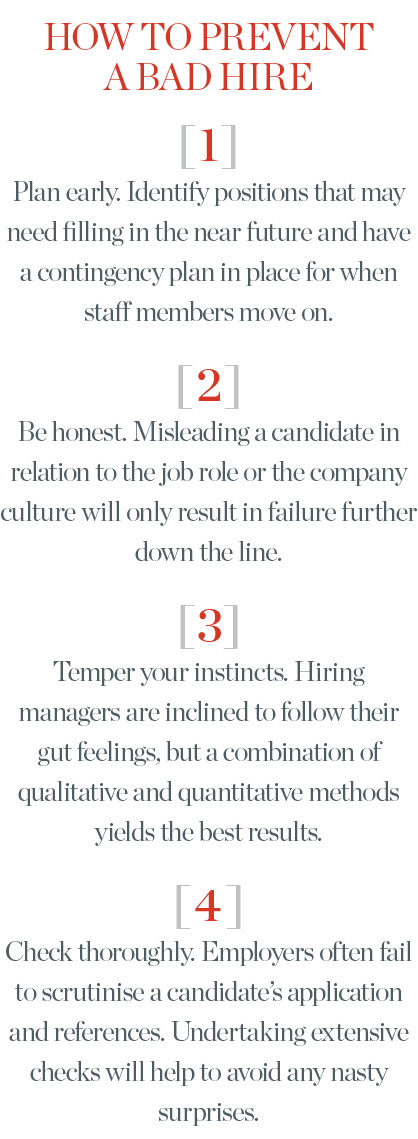

There are a number of reasons why bad hires are so common (see Fig 1), and it often starts long before the interview process has even begun. “Most companies don’t try to hire until they really need someone,” Liz Kislik, president of management consulting firm Liz Kislik Associates, told European CEO. “By that point, they’re under time pressure and they’re under pressure for the work or change that’s not happening.”

This, Kislik explained, can have a cascading effect. Given the need to find someone quickly, employers often jump at the possibility of a potentially suitable candidate. Others in the team then quickly agree, making it more difficult for someone to offer an opposing position. As Kislik explained: “The person who has an instinct that there could be problems with this candidate whom everyone else seems to like so much may feel that they shouldn’t raise [a] negative [viewpoint] – if they’re outvoted and the candidate gets hired anyway, then they’ll have to work with that person and they don’t want the new hire to know they were against the hiring decision, so they may not raise their concerns.”

Then there is the interview itself. Too often, employers avoid telling candidates the full truth about a role and the organisational environment in which they may soon be working. It’s almost a natural instinct to do so: as much as the individual being interviewed is trying to sell themselves, so too are those asking the questions. When it comes to high-level employees and sought-after talent, the inclination to do so becomes all the more apparent.

Herein lies a big problem for the long-term success of the hire: by not presenting the role and the company honestly, employers are unlikely to identify a suitable match. “Hiring managers might not actively want to mislead candidates,” Atta Tarki, CEO and managing director of executive search firm ECA, and author of Evidence Based Recruiting: How Google and Netflix Leverage Talent Acquisition to Gain a Competitive Edge, told European CEO. “However, by not disclosing the full truth, hiring managers are not allowing candidates to be truthful [in return] and [jointly] decide if the role is a good fit.”

By doing their homework, employers can often uncover any nasty surprises before extending job offer

In other words, if a candidate is put off when they hear, for example, the day-to-day tasks of the role and what the office culture is really like, then it is almost a certainty that they are not going to be the right fit. “Candidates hopefully know more about themselves than a hiring manager can find out in a few interactions,” Tarki said. “If the candidate thinks an opportunity is the wrong fit for them, they are probably right.” Should the candidate decline the role, they are, in essence, saving the organisation a great deal of time and money by not joining the team and leaving six months down the line. In fact, according to a 2017 CareerBuilder survey, companies lost an average of $14,900 (€13,390) per bad hire in 2016.

Tarki also believes that a common mistake managers make when conducting interviews is relying too heavily on their instincts. “This is not to say that hiring managers should rely on purely quantitative candidate attributes or hiring methods,” Tarki told European CEO. “The strengths of quantitative methods are that you can measure, standardise and replicate many of the outcomes; the strengths of qualitative methods are the richness and depth of the insights. My view is that both methods should be used as complementary tools when assessing candidates.”

Costly decision-making

Hiring the wrong person has a far greater impact than one might initially presume. Of course, there is the time and money required to find a replacement. Going through the whole process again – listing the vacancy, selecting appropriate candidates, conducting interviews and screening – is no small feat, particularly when it comes to senior positions.

“The costs of wasted salary, training and rehiring can all add up to a significant figure, but there are other key factors that are often overlooked,” Steve Girdler, Managing Director (EMEA and APAC) at HireRight, told European CEO. “These can be more difficult to measure and quantify, but may have an equally important impact.”

As Kislik explained: “Errors in the new person’s judgement could cause the loss of millions of dollars if, for example, they eliminate traditional marketing campaigns because they prefer other approaches and don’t take company history seriously.”

The reputation of the organisation could also come under threat, particularly if the employee’s role is client-facing. Bad hires can cause irreparable damage to business relationships. This, in turn, can have a massive impact on the company moving forward, jeopardising agreements with existing and prospective clients. Put simply, employees represent the organisation they work for – if they’re ill-mannered or inept at their job, it reflects poorly on the business and everyone within it. “What’s worse, people who have had bad experiences tend to tell their colleagues and friends about it, amplifying its fallout,” Girdler said. A good reputation is hard to build, but it can be dismantled almost instantly.

Furthermore, there’s the exponential effect that a substandard recruit can have on company culture and team spirit. Not only does a bad hire often result in a lower quality of work, but it can also breed resentment, especially if others have to pick up the slack. “Bad hires can become rotten apples for any organisation, having a negative effect on those around them [and] impacting company culture,” Girdler explained. “Many departments and companies spend a lot of time and money developing a positive employee culture in their business, but sometimes just a few individuals can unpick all [of] that good work.”

Accordingly, team members begin to question the management, especially if said individual is kept on in spite of being ill-equipped for their job and proving detrimental to the business. Combined, these factors can increase staff turnover. As Kislik explained: “[This can cause] a significant loss of expertise, in addition to mounting replacement costs. Perhaps even worse is if disaffected employees remain, but no longer collaborate or produce at the level [of performance] they once did.” According to CareerBuilder, the average cost of losing a good hire is nearly $30,000 (€26,960).

Honesty is the best policy

Fortunately, there are lessons that can be learned and mistakes that can be avoided. The first involves preparing adequately for the recruitment process – a detailed job specification that clearly outlines the tasks a candidate will be expected to carry out is crucial. While a description of the type of person an organisation is seeking is important, it is not necessary in terms of weeding out those who believe they aren’t a good fit for the role.

This step also helps hiring managers during the interview stage – when they are well versed in the role’s most important duties, understand which requirements have to be met and are aware of what type of experience is necessary, hiring managers are better equipped to identify the right candidate during face-to-face meetings. As for the interview itself, Tarki advises the promotion of truthful conversations: “Let the candidates interview you about the role and the company as much as you interview them. And then be truthful in answering the candidate’s questions, even if it means being vulnerable by admitting aspects of the company culture or the role that you wish were different.

a common mistake managers make when conducting interviews is relying too heavily on their instincts

“You can still wrap up the conversation by telling the candidate that admitting aspects of the role that can be perceived as a downside does not mean that you are discouraging the candidate from taking on the role – it means that you are trying to ensure a genuine fit.”

Given the amount of company-related information available on the internet these days, being truthful has become more crucial than ever. “In the era of Glassdoor and a multitude of other sites, many candidates will research your company culture and the realities of the most common roles at your firm before interviewing with you,” Tarki said. “So the only question is, ‘Who’s fooling who?’”

Girdler agreed: “When hiring, it is wise to consider how well an individual is likely to fit in with your company culture. This will ensure that both the business and the candidate would be happy if they joined the team. Talking about your culture frankly and openly during the interview process is a good way to avoid any surprises further down the line.”

If a candidate is aware that the company has misrepresented itself during the hiring process, then it sets a precedent for a dishonest relationship moving forward. Starting off on such grounds could lead to disaster. “The costs of a [mis-hire] go well beyond the salary investment,” Tarki told European CEO. “By focusing on truthful conversations, you are increasing the chances of a good fit, which, in today’s competitive job market, is becoming increasingly valued by candidates and ensures longer-term success.”

Call to account

Comprehensive checks on the individual – including the contacting of previous employers – are often cast aside despite being a crucial part of the application process. But by doing their homework, employers can often uncover any nasty surprises before extending a job offer. Naturally, the higher the position in the organisation being advertised, the more time is required to effectively screen a new recruit before being brought on board.

“Hiring managers are only human… and mistakes can still be made,” Girdler explained. “That is why it is so important to utilise background screening with your new hires before they join your organisation. By verifying a candidate’s credentials, education qualifications and employment history – essentially determining they are who they say they are and have done what they have claimed to have done – you can’t guarantee that your next hire will be a high-flyer, but you can be more confident that they genuinely have the experience and qualifications that they claim.” Having an experienced human resources team in place or using reputable recruiters, while also carrying out multi-stage interviews, can significantly reduce this risk.

If, however, someone does fall through the cracks, the first course of action is to have an honest, direct conversation with the new hire. It may well be that by sharing concerns, a mutually beneficial outcome can be reached. Perhaps the new recruit is not satisfied in their current role or department and would be better suited elsewhere in the company. It may even be the case that they are willing to make a change and try again. If so, focused feedback is key.

Making the cut

There are times, though, when a bad hire is damaging to a company regardless, and shifting them around is simply a case of moving the problem elsewhere. In this instance, it’s essential to make their transition from the organisation as smooth as possible.

Offering severance and outplacement support might seem to some like an unnecessary expense, but it’s an important step that should not be missed. “Unlike situations of long-standing inadequate performance, the dismissal of a new hire is an indication that something went wrong with the selection or onboarding [process],” Kislik said. “The new hire may actually recognise that things are going badly, and may be grateful for a way to make a smooth exit… If the new hire left a job to come work with you, you have some responsibility to help them transition out in a way that helps them find their footing again.”

Kislik also advised fast action: “Once it’s clear that the new hire is not going to be successful, move quickly to make the change. Leaving them in place while you’re trying to find a replacement or while you get past your busy season will only [cause] more damage.”

In terms of maintaining a good reputation, it pays dividends to end working relationships on a positive note. It also bodes well for the team that remains – knowing that upper management handled the situation well is important for staff morale and their confidence in the company. To remove staff members without going through the proper channels, even when they haven’t been performing well, can cause anxiety within an organisation and breed an atmosphere of distrust.

“In addition to dealing with the individual, conduct a formal review of your recruitment and hiring processes to determine where you could have been more rigorous, more attuned to subtle cues or more specific in reference-checking to ensure you don’t repeat the

negative experience,” Kislik advised.

We all make mistakes (to err is human, after all), but hiring the wrong person for a job can prove disastrous. Luckily, there are ways to reduce the likelihood of this happening – it just takes time, preparation and diligence. The interview itself is extremely important and must be conducted with forthrightness in order to find the right fit for both the role and the company.

Of course, even with these fail-safes in place, there is no guarantee a new recruit will prove successful; moving quickly and acting in good faith, however, can ensure each link in the chain is as strong as the last.