Winston Churchill once said that “we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us”, and today there is a great deal of scientific evidence to support his claim. Recent advances in cognitive research show that our environment has a significant effect on our brains, our health and our social behaviour.

If physical spaces can influence our behaviour, then it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest they can also be used to shape a company’s culture or improve productivity. Despite this fact, there are very few design firms currently incorporating this idea into their work. Fortunately, Space, a Mexico-based architecture firm, is working to change this fact.

European CEO spoke to Juan Carlos Baumgartner, CEO of Space, about the company’s ambition to create architectural designs that are not only beautiful, but serve a social purpose too.

Changing minds

The architects at Space believe the power of design can change the world for the better by using physical environments to influence the way people think and act. This is an ethos that has deep roots for the company’s CEO.

“In my personal background, I studied ambient physiology as part of my undergraduate degree, and it always intrigued me how little traditional architects and architectural firms knew about behavioural psychology,” Baumgartner explained. “Since our firm was founded in 1998, we decided to challenge the status quo and find a common ground between disciplines like psychology, human behaviour and neuroscience, among others.”

By exploring the ways space can act as a cognitive intervention, good design can have a truly meaningful impact on society

However, as with many innovative approaches, the real challenges emerge when the time comes to translate theories into action. Over the past 20 years, Space has developed an approach called ‘hybrid methodologies’ in order to test its design solutions. By working with a neuroscience lab in Canada, the company is able to investigate the correlation between a physical space and an individual’s state of mind.

In fact, Space has found that design can be used to impact more than just a person’s thoughts. By forcing people to use their bodies in different ways, for example, it’s possible to influence internal chemical reactions, such as increasing testosterone or decreasing cortisol, by encouraging changes in posture.

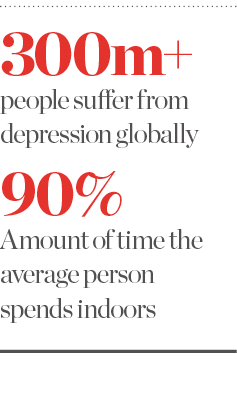

“Another idea that is gaining more traction among architects is epigenetics,” Baumgartner said. “This is a theory that your genetic expression can be altered by your experiences, without altering the genetic code itself. Most humans spend 90 percent of their time indoors, in environments designed by humans. If we can design experiences in a particular way, then we can change not only our body chemistry, but also our genetic expression.”

For a long time, designers worked in isolation from other fields, creating physical spaces based on their aesthetic beauty alone. Today, the most creative companies in the industry are realising that there is so much knowledge to be gained from broadening their horizons.

Beyond beauty

Far from being someone who simply ensures an office looks nice or fulfils the criteria of his client, Baumgartner is starting to incorporate social responsibility into his work. “We live in a historical moment as a society, where almost everything we know is going to be disrupted by innovative new technologies,” he noted. “This represents a huge challenge, but also an enormous opportunity. I believe this is where designers have a huge social responsibility.”

Physical environments have the power to shape culture, behaviour and wellbeing, so it is possible to explore deeper meanings through design. It is not enough for them to simply be beautiful. Baumgartner believes that by exploring the ways space can act as a cognitive and biological intervention, good design can have a truly meaningful impact on society.

“We need to start asking why so many kids suffer from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or why there are so many depressed people or what we are doing that is causing thousands of elderly people to develop dementia,” Baumgartner said. “I’m sure that in many cases the answers to these questions will be found – in part, at least – in the environments that we have created for ourselves.”

This is not to say beauty is no longer a key concern for architects – it simply means that other considerations are increasingly important. One of the ways Space is exploring these loftier goals is through its Design for Happiness theory.

“We have created a culture that has accomplished amazing things over the years,” Baumgartner said. “In general, we live longer, we eat better and we have more things, but we haven’t actually done much to improve overall levels of happiness. Today, depression is the most common illness involving the brain. The World Health Organisation estimates more than 300 million people in the world suffer from the condition and fewer than half of those receive treatment.”

Research indicates that happiness often stems from how we react to our experiences, both good and bad, and Space has been exploring how design can influence this. Currently, the company’s Design for Happiness theory is examining how architects can help individuals break out of the “loops they are stuck in”, according to Baumgartner. By understanding how design affects cognitive processes, it can be used to help individuals break free from their current limitations.

‘Neuroarchitecture’ may be a new area of study, but it is gaining traction fast. For example, it has been proven that people in hospital recover faster when they have access to natural light, and there is plenty of research suggesting schoolchildren perform better when they use their body as part of the learning process. The design of physical spaces is key to both of these examples and many others.

Healing spaces

More recently, Space has been working with the latest brainwave measurement technology to better understand how the human mind is affected by physical space. By using equipment that measures five different types of brainwave, the company has been able to determine what each brainwave represents. Ultimately, Space hopes to be able to establish whether certain states of mind are related to specific physical environments.

“My vision is that in the future we will be able to help cure depression or ADHD with the use of specific types of space – you will go to a doctor and they will prescribe specific environments,” Baumgartner said. “Then we will have an alternative to the solutions that we know today, which are mostly limited to the use of pharmaceuticals.”

If Space is to accomplish its ambitious target of using design for social good, then more research needs to be conducted. Fortunately, the company understands its goals will require a significant shift in the mindset of corporations and individuals alike. Baumgartner is currently working with a group of psychologists to create a change management process that will help alter the way people view their physical surroundings.

As the design world increasingly utilises the cutting-edge research being undertaken in the field of neuroscience, there is hope that physical spaces will serve more than just an aesthetic or practical purpose. By enabling people to be more productive, happier or even healthier, Baumgartner believes design could make a meaningful difference to people’s lives.

“In general, the aim of Space is to help society accomplish its most meaningful goals using architecture and design,” Baumgartner said. “More specifically, it is to leave a better and happier world for my kids and future generations.”