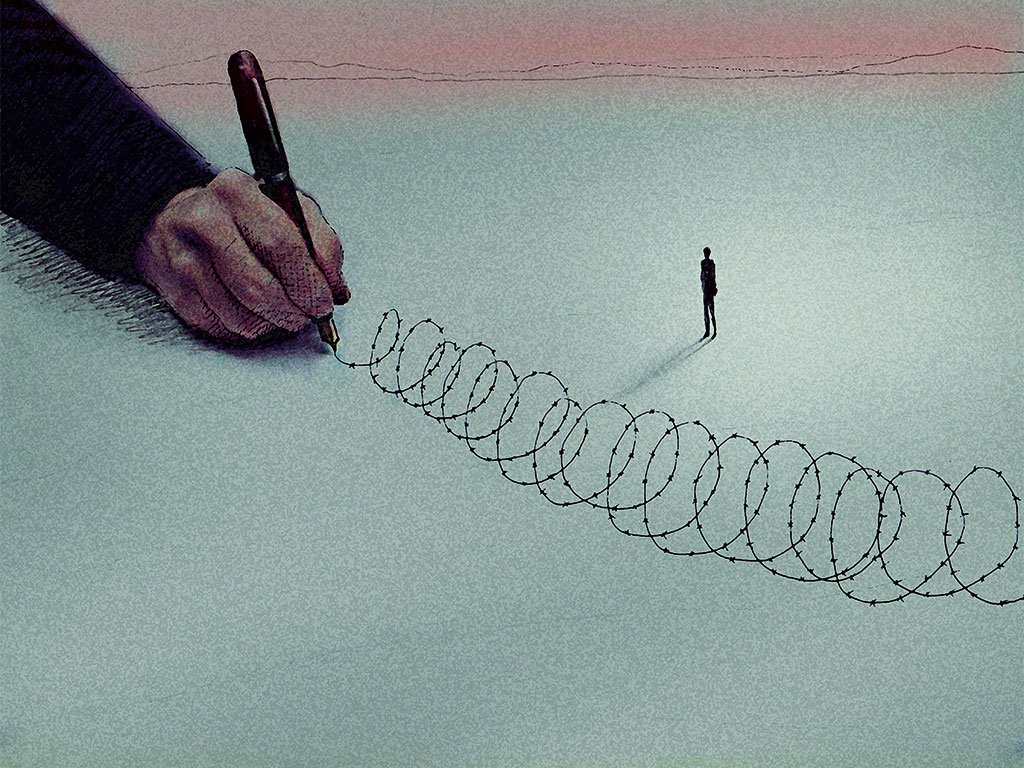

The long-held dream of a borderless Europe, which became reality in the mid-1990s, is fading fast. Italy is blocking an EU decision to bribe Turkey to keep refugees from crossing over into Greece on their way to Germany, Sweden, or other northern European countries. In response, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble has called for solidarity, warning that otherwise the border guards might soon be back at their posts, beginning with the German-Austrian frontier.

To be sure, the dissolution of the Schengen Agreement, which instituted passport-free travel within most of the EU starting in 1995, need not mark the end of the European project, at least not in principle. Economically, border controls act just like taxes; they distort activity by increasing transaction costs and reducing cross-border flows of goods and services. Without them – and, more importantly, with a single currency – a market is more effective. That does not mean, of course, that the single market cannot work with border controls or multiple currencies. It simply means that such renationalisation would carry enormous costs, in the form of substantially reduced productivity and significantly lower output.

The end of Schengen

Given these costs, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has stressed that “killing” Schengen would undermine the EU’s goal of “ever closer union” – an objective to which, admittedly, several EU members have signed up only reluctantly. The UK is the most vocal sceptic, but Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and pretty much the all eastern European members have never been enthusiastic about shifting focus from national prerogatives. The refugee crisis has thrown this discord into sharp relief.

As a result, Europe’s densely knit network of interdependencies is beginning to unravel. The benevolent hegemon, which used to be the French-German couple, is missing. A focus on national (and in some places, like Catalonia and Scotland, regional) issues is gaining ground, in line with the incentives of policymakers, whose constituencies are national (or regional). Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s call for a quid pro quo – a loosening of the eurozone’s fiscal rules in exchange for accepting the deal with Turkey – is entirely understandable in this light. But it puts the EU on a slippery slope.

The irony in all of this is that Germany, which was perceived as ruthless during the European sovereign (and private) debt crises, is now calling for solidarity

The irony in all of this is that Germany, which was perceived as ruthless during the European sovereign (and private) debt crises, is now calling for solidarity. Supported by other northern European creditors, Germany enforced its fiscal principles relentlessly, despite the systemic consequences for those it was pressuring (Greece and Spain, for example, now have different governments). Whether the adjustment policies have been successful remains a subject of heated debate; what is not in doubt is that they produced many losers – most notably among the most vulnerable, who now largely perceive the EU-Germany consensus as threatening.

Against this background, anti-establishment parties across Europe oppose policies that reflect this German-inspired approach. This explains, for example, the similarity of the economic platforms offered by the far left and far right in France. Even mainstream parties are under pressure to cater to this insurgent sentiment; defending EU policy proposals is a surefire way to lose an election.

That is why, as Germany struggles to cope with some 1.5 million refugees, Schäuble’s call for solidarity is falling on barren ground. Everybody, beginning with France, is hiding. It’s payback time. Burden sharing – that is, a fair allocation of refugees throughout the EU (to be hashed out politically) – appears to be a pipe dream.

Bleak outlook

Economically, accommodating refugees will be a challenge for quite some time. But if one takes a longer view, absorbing the newcomers should be an opportunity – if it is appropriately handled. In the meantime, however, not only Germany, but also Sweden, the Netherlands, Austria and others, are running up against what is deemed to be politically feasible. This implies that no EU-wide response can be expected, and thus that Schengen is probably doomed.

This would be more than a symbolic loss for European citizens. And, of course, re-erecting national borders does nothing to address the underlying issue. Refugees would just be pushed back to Greece, the most fragile and vulnerable link in the chain.

As uninspiring as this might sound, we must now consider the prospect of the end of the European Monetary Union and the EU as we have known it. The goal is not simply to highlight the lost opportunities associated with such an outcome; those would clearly be sizable, especially if the currency union had to be untied. The point is also to show that the minimal conditions for the EU and the eurozone to work in their current form are lacking.

Foremost among these conditions is a shared diagnosis of the EU’s problems and a common philosophy. Renzi and Schäuble, for example, have strikingly contradictory views on crucial issues, from fiscal policy to the banking sector. Renzi criticises the EU, while laying the blame for the consequences of new creditor bail-in regulations squarely at Germany’s door. For the same reasons, French President François Hollande puts internal security first (possibly in line with the preferences of his electorate), and honours fiscal rules inconsistently. It doesn’t help that applying German or EU proposals on refugees would not exactly strengthen his re-election chances.

If EU member states were to pursue their enlightened self-interest, they would nurture ever-closer union, with solidarity – fiscal and otherwise – between north and south. Instead, they are increasingly scapegoating Europe and embracing a national discourse. Once again, Europe seems to be sleepwalking into crisis. One hopes that it wakes up in a safer place than it has in the past.