The casual observer need only look to the standard billboard, internet banner or TV ad break for evidence of the modern obsession with health and wellness. From food to clothes, the overriding message is that mindfulness makes for a better product, and beauty companies have been quick to flaunt their natural, organic, Fairtrade or ethical credentials.

The growth in mindful consumption – more popularly known as conscious consumerism – has far-reaching consequences, and no company serious about survival can afford to ignore the shift in shopping habits. Shoppers today are well informed about the impact unpalatable practices have, not just on them but on communities down the supply chain. And where spurious company claims were in the past accepted without a whiff of suspicion, scrutiny has never been sharper than it is now.

This is by no means a European phenomenon; Cone Communications’ latest Social Impact Report stated 89 percent of US consumers were likely to switch brands based on company values. Likewise, Nielson’s Global Survey on Corporate Social Responsibility found 55 percent of online consumers would pay more for a product or service provided by a company with a positive social or environmental impact.

Beyond the cosmetic

As demanding as this new subset of consumers is, there are advantages for companies sympathetic to their values. Beauty and cosmetics are a case in point, and as purchasing decisions become more informed, a preference for natural and organic is certain to become the dominant trend.

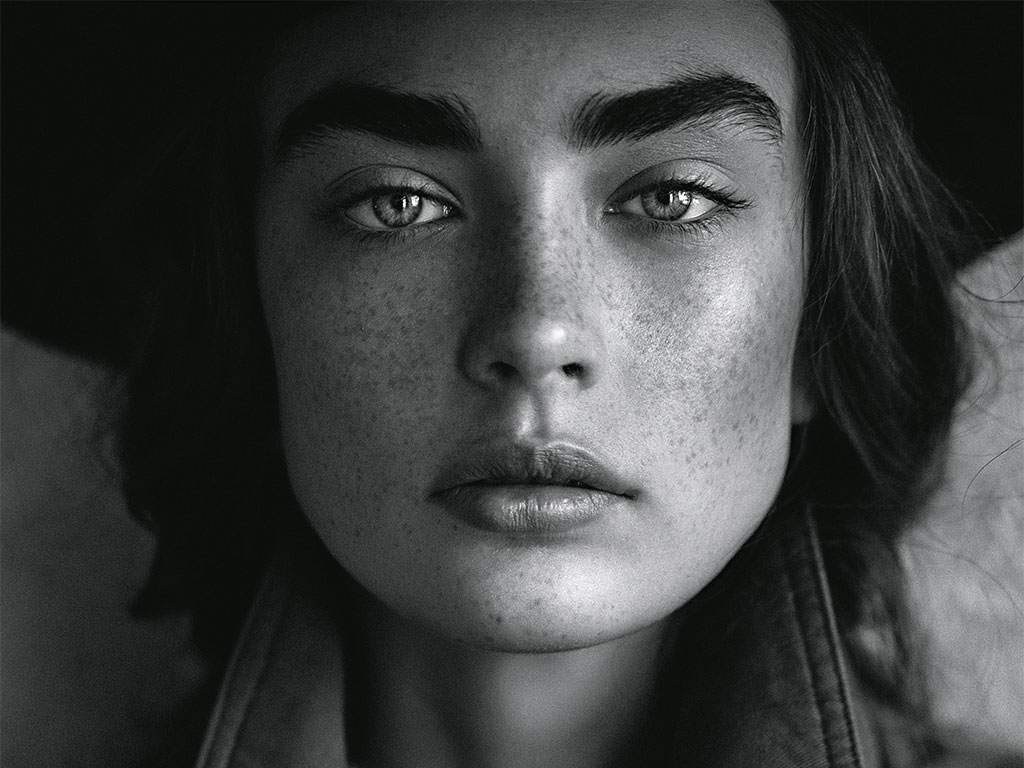

Companies with a stated commitment to natural, organic, Fairtrade or ethical items have found their calling

Research undertaken by J Walter Thompson Intelligence shows the majority of consumers are actively seeking natural or organic beauty products due to anxieties concerning the risks – ill-conceived or not – of using conventional or highly synthesised products. In a survey, Organic Monitor found the major motive for UK consumers was avoidance of synthetic chemicals, with 90 percent putting it down as either important or very important when making a purchase. Mintel’s assessment is that these “attitudinal changes toward natural ingredients have acted as a catalyst in the rise of ‘kitchen beauty’ – products that look like they have been [made in a kitchen], but still reflect the latest cosmetic understanding – and is driven by a desire for consumers to feel in control of their beauty products”. Consumers, it seems, now more than ever want to know what goes into their products, and companies with a stated commitment to natural, organic, Fairtrade or ethical items have found their calling.

The market in Europe for natural and organic personal care is set to grow at a compound annual growth rate of over 9.5 percent between 2014 and 2019, owing to a projected increase in disposable incomes and a willingness to pay over the odds for natural and organic products. According to Grand View Research, the global market for organic personal care is on course to reach just shy of $16bn by 2020, and demand for organic and natural haircare, skincare and cosmetic products is expected to augment the organic personal care market.

The organisation also went on to note that this trend hasn’t been lost on major names, and L’Oreal’s acquisition of Kiehl’s in 2000 and the Body Shop in 2013 is testament to its pervasiveness. More recently, the French cosmetics giant bought the natural haircare company Carol’s Daughter, and in 2015 Estée Lauder bought natural skincare brand Rodin Olio Lusso, each with a view to expanding their organic product portfolio.

As significant as this trend is, ‘natural’ companies occupy only the smallest percentage of the beauty and cosmetics market. A report by Kline went further in calling out the natural personal market as “extremely fragmented”, and in 2014 the top five companies accounted for barely a quarter of total sales. As much as consolidation has lifted the sector, increased oversight could galvanise the market at last.

Full disclosure

In particular, greater availability of information on natural and organic products is driving growth, and apps such as Skin Deep and Think Dirty allow customers to determine the legitimacy of any claim to the ‘natural’ tag. According to Amarjit Sahota, founder and CEO of Organic Monitor: “Mobile phones and the internet are making consumers more informed than at any other time in history, with information accessible on consumers fingertips.” Research by the organisation shows the primary source of information on natural and organic personal care products in the UK was the internet (stated by 35 percent of respondents), whereas the same study in 2007 put friends and family way out in front.

Speaking to Business of Fashion, Stéphane De La Faverie, GM of Origins, Ojon and Darphin, said: “People are just more and more aware of what is in the product, and I think it’s the result of digital and social media.” In light of these concerns, the EU has banned over 1,000 chemicals from cosmetics, and greater numbers are aware of their effects on health.

Natural how?

Greater awareness aside, nothing quite ignites discussion on the topic more than the question of what constitutes ‘natural’, and the term’s lack of specificity is itself a cause for concern. Rightly or wrongly, consumers perceive ‘natural’ to mean higher quality, yet there’s very little in terms of concrete indicators to distinguish natural from whatever else has come before.

Apps such as Skin Deep and Think Dirty allow customers to determine the legitimacy of any claim to the ‘natural’ tag

Seeing that customers are warming to natural ingredients, companies have been quick to talk up the parts of their products that appear to fit the bill. And where some take organically certified ingredients as proof of the fact, others opt for a picture of natural-looking ingredients on the packaging. Face value commitments like this give shoppers invested in health and wellness good reason to feel cheated, and it’s in this department that apps to differentiate between the two ends of the scale have value. Likewise, certification could make or break the sector. Fortunately, COSMOS certification will come into effect this December to cover both natural and organic, brought about by the five main European certifiers.

Sahota echoed some of these concerns, going so far as to say “there is no agreed definition” of ‘natural’ and ‘organic’ for beauty and personal care products. Unlike foods, the ‘organic’ term is not regulated. “Voluntary standards, such as Soil Association, COSMOS and Natrue”, she said, “are being adopted, however there are also variations in these standards. Where it gets difficult is the chemistry involved in making cosmetic formulations; there are chemical processes and synthetic ingredients that are not easy to classify as permitted/prohibited by certification agencies.”

For as long as the criteria for natural beauty products remain unclear, manufacturers are unlikely to abolish chemicals they believe to be important. The benchmark set by leading beauty brands, not to mention the creation of certification and evaluation systems to legitimise their commitments could go some way towards making this minority sector mainstream. Without them, the ‘natural’ tag is simply cosmetic.