Today, 70-year-old Ricardo Salgado is forbidden from leaving Portugal. He is under investigation for fraud. Humiliatingly for a man who identified himself with his country’s future, he only escaped custody through a €3m bail. In the meantime, investigators are working their way through the books of Banco Espírito Santo (BES), whose name translates as Holy Spirit Bank, to try and establish exactly how it managed to rack up what has eventually amounted to €10bn in losses without them knowing.

The timing of the collapse of BES could hardly have been worse for Portugal. It was only earlier this year that its economy was officially declared healthy after a nervous and painful three-year rescue. Inevitably, the failure of the institution sent tremors through a country that is still very much on the mend.

The failure of BES caught everybody by surprise, except perhaps Salgado. On July 30 2014, under pressure from the Bank of Portugal, it released results for the first half of the year. Losses were revealed at €3.57bn, almost all of it piling up in the second quarter. The figure, which stunned the central bank, the government, the financial industry and the markets, told a stark story. Portugal’s third biggest bank was insolvent.

Rise and fall

1869

José Maria do Espírito Santo e Silva enters the financial world, offering lottery and currency exchange services at Lisbon’s Caza de Cambio. He then opens a number of banking institutions

1915

After José Maria’s death, his family dissolves his banking institutions and establishes in their place a single, unified bank –Casa Bancária Espírito Santo Silva & Cª

1920

The bank is converted into a limited-liability public company and, for the first time, the name is officially changed to Banco Espírito Santo

1937

The bank merges with Banco Comercial de Lisboa to become Banco Espírito Santo e Comercial de Lisboa, significantly improving its position and standing

1975

Following the Carnation Revolution, private banks are nationalised. This leads the Espírito Santo family to establish operations in Brazil, Switzerland, France, the US and Luxembourg

1986

With the help of other banks, most notably France’s Crédit Agricole, the bank resumes operations in Portugal. Partnerships are also formed with Swiss bank UBS and Luxembourg-based KBC

1999

Having commenced operations in both Spain and China during the early 1990s, the bank’s name is once again changed to Banco Espírito Santo

2014

Following years of reliance on leveraged operations, Banco Espírito Santo, spanning four continents and 23 countries, collapses. Shareholders and investors lose more than €10bn

Snowball effect

Carlos Costa, the Governor of the Bank of Portugal, was particularly incensed at the black hole in the BES accounts. Just two weeks earlier, Salgado had approved the release of figures that showed that the institution carried exposure of just €1.24bn to the family-controlled holding company, Grupo Espírito Santo. At a figure of €1.24bn the bank was more or less in the clear.

Reassured, the central bank then publicly confirmed that BES had sufficient capital to absorb any shocks that may occur in the family’s non-financial businesses. In short, there was nothing to worry about. But when the awful truth emerged that the actual figure was nearly three times what BES had said, a furious Costa did not mince his words. In a stinging press statement, he blamed the abrupt deterioration in the bank’s position on “a series of management actions seriously detrimental to the interests of Banco Espírito Santo.”

Worse, he said, was the fact that “these actions had ignored directions issued by the central bank”. Nor had they been reported by any member of the management or supervisory board of BES “on the date they occurred”, as was clearly required. In other words, Salgado and his management team had ridden roughshod over the instructions of the central bank. The clear implication is that Salgado did not feel bound by his obligations to the Bank of Portugal.

A whole series of events at this point became inevitable. The unexpected torrent of losses meant that BES no longer complied with the minimum capital ratios for Europe’s banks, enforced since the financial crisis. Indeed it was a whole three percentage points below the minimum. On August 4, the ECB cut BES from its monetary policy operations, meaning it no longer had access to the ECB’s normal liquidity window. A panicked public started to pull funds. On the stock market, BES shares collapsed to 12 cents, forcing the Portuguese Securities Market Commission to suspend » trading. Next, the agencies slashed the bank’s rating, with more cuts likely.

Facing the prospect of contagion across the banking community in Portugal, with knock-on effects to the stability of the European financial system, the government had to act fast. For the first time since the financial crisis, a major European bank had to be wound down under the new ring-fencing regulations. In short order, a new bank called Novo Banco was established with the deposits of BES and other secure assets. In one well-timed swoop, this action saved the retail bank. Novo Banco now holds €4.9bn in assets, all of it provided by the specially created EU Resolution Fund.

Emergency tactics

The establishment of Novo Banco is a classic ‘good bank, bad bank’ strategy. The arrangement became possible because of the Resolution Fund, which, in the wake of the financial crisis, was set up two years ago for exactly this kind of emergency. The funds came from a levy on the finance sector. Even so, the fund fell short of what was required because it had not been possible to accumulate €4.9bn in just two years. As a result, the Portuguese Government was forced to plug the gap with a temporary loan of €4.4bn.

As is standard practice in the applied strategy, while the good assets went into Novo Banco, the rest have been dumped into the old institution. At this stage it seems highly unlikely that bond holders will get much or anything back. Although the Bank of Portugal insists tax payers are off the hook, they may yet indirectly foot some of the bill.

The top-up loan of €4.4bn tapped EU and IMF rescue money that was left over from the country’s bailout in 2011, after its sovereign debt was savaged by the financial markets. The hope is that the €4.4bn will be repaid by the eventual sale of Novo Banco, but there is no guarantee.

Portugal’s regulators have come under fire for not moving sooner. Certainly, it took them an unconscionably long time to get on the case, especially considering there had been rumours in the market for at least a year that BES (and perhaps the entire family-controlled group) was in trouble and had been issuing debt in great swathes to shore up the finances.

Last year, Salgado had attempted a negotiation with the central bank to discuss what amounted to a lifeline. With breathtaking nerve, the head of the banking dynasty had asked for €2.5bn, a request which Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho turned down flat on the basis that taxpayers will no longer support failing banks. In a ringing affirmation of the post-crisis mentality, his exact words were: “We will not use public instruments to solve problems of a private nature. When private companies do bad business, they have to bear the costs.”

However, the revelations made in the meeting served as a red flag and the central bank began to take a greater interest in the non-financial side of the business and its numerous global projects. In technical terms this was a cross-border audit – known as a horizontal review of credit portfolio impairment – that does not normally come under the purview of a central bank.

The results horrified Costa. In a few weeks Bank of Portugal investigators detected what they described as “a fraudulent funding scheme between the companies within the groups”. That is, money was being channelled from BES through Group Espírito Santo and various offshore structures. As soon as the investigators produced evidence of the alarming links between BES and the rest of the family empire, the central bank sprung into action and it was no longer possible for Salgado to disguise the precarious state of the company. By late 2013, the group-owned companies, starved of cash, began to default one by one.

Driving blindfolded

Over the last few years Salgado had plenty of opportunities to reverse his ultimately disastrous incumbency at the bank. The patriarch, who qualified as an economist, appears not to have taken a single substantive remedy to correct his institution’s steady decline. First, in the turmoil of the financial crisis, he refused to batten down the hatches for the bad financial weather. Recklessly, as it turns out, BES was the only one of Portugal’s three biggest publicly-traded lenders that did not request state aid, even though the entire banking system was fragile at the time. In the light of the latest revelations, regulators now assume that Salgado may have been hiding something, thus he was reluctant to open the books, as would have been required as a prerequisite for government support.

Next, he began marketing short-term debt to retail clients to keep the family-owned assets afloat. By last year, a fund called Espírito Santo Liquidez held €1.7bn in near-due commercial paper issued by various companies within the empire. It was the largest fund in Portugal. “All these funds date from 2009”, a Portuguese banker told Reuters. “Because of the crisis they were forced to do other things that were not totally legal as the situation got worse.” Then Salgado faced down internal opposition. Even late last year, when the situation was deteriorating rapidly, he was able to head off an internal battle with his cousin José Maria Ricciardi, after the latter had warned, in a searing behind-closed-doors debate, that the older Salgado was steering BES over a cliff. According to insiders, Ricciardi stormed out after senior members of the family voted to leave the repair work in Salgado’s hands to preserve family unity.

Finally, on May 20 BES went to the capital markets, still without taking concrete, if painful, steps to sort out the mess. In this particular fundraising exercise, BES hid behind a PR campaign that put homely sayings above disclosure. In a reference to the bank’s longevity and, it seems, impeccable reputation, it sold the fundraising under the slogan ‘Wisdom is something that needs time to grow’. That time was running out fast.

The extraordinary thing about the entire saga is that Salgado appears to have identified himself and his institution as pillars of the Portuguese economy that should, when push comes to shove, be supported by the state, even though the entire structure of the BES-led empire was purpose-designed for the ultimate benefit of the family. With some 250 members of his family in senior positions, Salgado ensured loyalty to himself. He refused to sell off family-controlled assets if it meant diluting the Salgado clan’s 25 percent stake in the bank. After 22 years at the top of a dynasty created over almost 150 years, Salgado clearly considered himself indispensible, certainly to the institution and probably to Portugal itself. Indeed, he took the name of the bank into his given name; he is known as Ricardo Espírito Santo Silva Salgado. Within Portugal, he was dubbed dono disto tudo, meaning ‘owner of everything’.

Cause and effect

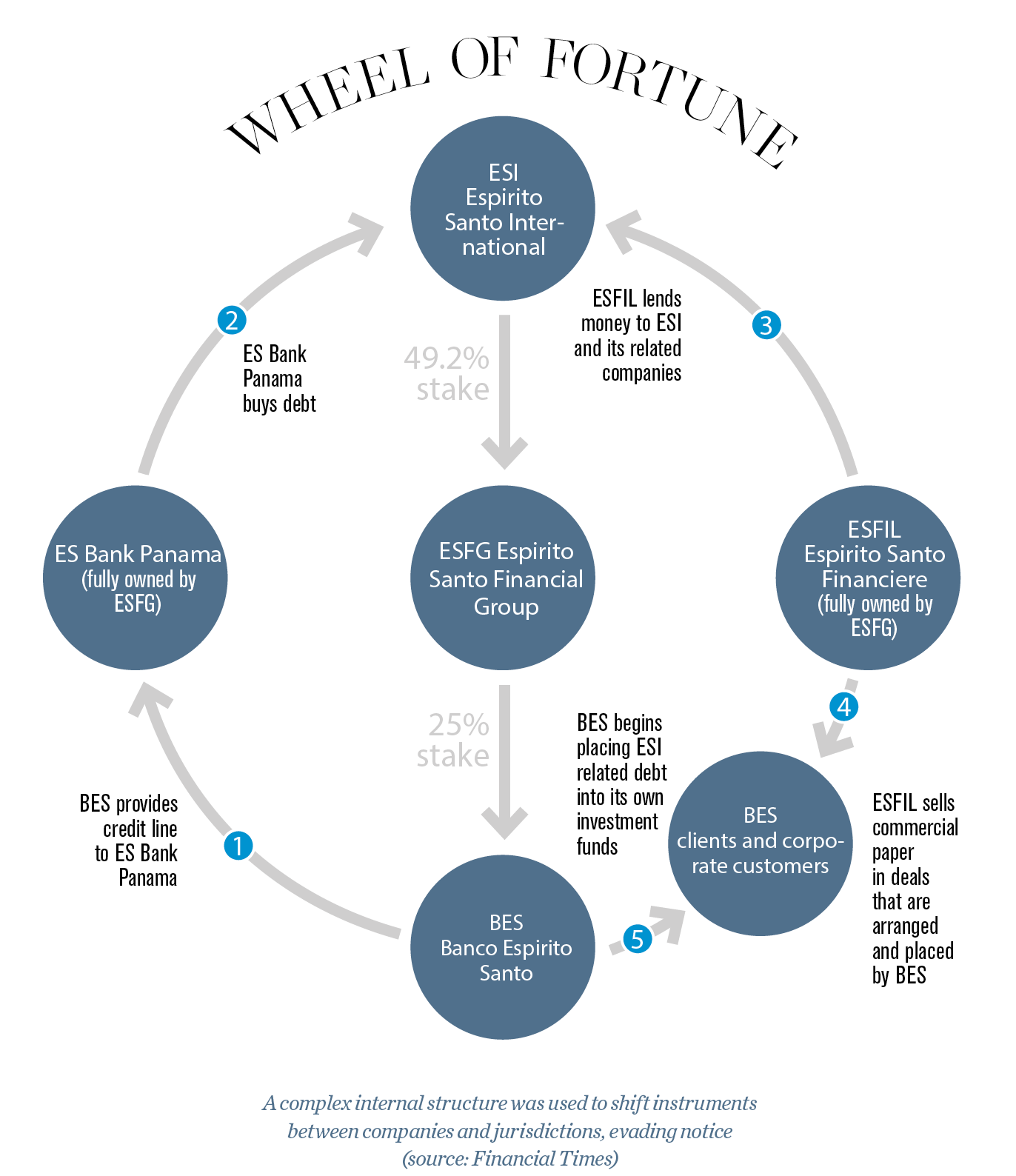

Salgado presided over an elaborate corporate structure that allowed him to create a money-go-round. In the middle was the financial group. In turn, that was sandwiched between the international group that handled the non-financial assets, and the bank itself. The various debt instruments were shifted between a bank in Panama and a Luxembourg identity in a way that remained largely invisible for years.

The structure was so opaque, in fact, that the central bank appeared to know almost nothing about the Luxembourg structure or the other entities beyond Portugal’s borders. Gradually, Bank of Portugal investigators unearthed the disturbing information that the empire had been built up largely on leverage. Its debt ratios had progressively skyrocketed as Salgado steered the bank beyond banking and into a commercial empire with interests in real estate, hotels and agriculture. These ventures were built up using the family’s 25 percent stake in BES as collateral.

According to a senior Portuguese business source, they kept growing the asset base and investing heavily, while never achieving the essential returns. For all his vaunted banking skills, Salgado was running faster and faster to stay in the same place. “The family eventually lost track of all these different businesses”, explains Ricardo Cabral, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Madeira. And rather than raise money by selling down the controlling stake, Salgado adopted the high-risk and eventually fatal strategy of issuing more and more debt. “It kept on postponing the problems by rolling over debt with short maturities and high interest rates”, adds Cabral.

Some investors are already baying for Salgado’s blood. “They ought to treat him like Madoff”, insists Mario Begonha, a 77-year-old sociologist, expressing a view shared by many of the clients of the collapsed bank. “He should be put away for 25 years, the maximum penalty.”

Any eventual punishment depends, of course, on the conclusions of the current forensic investigations. While he awaits those results, Salgado has shifted out of Lisbon into a five-star hotel in the coastal resort town of Estoril. Apart from a brief interview with a local newspaper, he has not made any sort of public comment on the affair. However, in that interview he appeared to absolve himself of blame for the situation: “I will fight for honour and dignity; mine and my family’s.” Indeed he even went so far as to quote Pope Francis, in a line drenched in proud stoicism: “Don’t cry for what you have lost: fight for what you have.”