Every year, more than 2,000 of the world’s wealthiest and best-connected individuals converge on the tiny mountain resort of Davos to discuss, debate and hopefully resolve some of the most important issues facing our planet. In January, the World Economic Forum (WEF) will host its 48th annual meeting in a world that has changed markedly since its inaugural get-together in 1971.

In that time, however, WEF has faced almost as much criticism as it has praise. While the forum has rightly championed the role it played in calming Aegean disputes between Greece and Turkey, German reunification and the end of apartheid in South Africa, it has also been denounced as little more than a vanity project. With tickets for members costing upwards of $20,000 (€17,100), the forum may now be better known as a place for elite networking rather than overcoming global challenges.

Having said that, WEF does raise thought-provoking questions at its annual meetings – many of which touch upon the most significant stories of the previous year. In 2018, the programme will focus on ‘creating a shared future in a fractured world’, with the threats of climate change, secession and workplace automation likely to dominate discussions. As heads of state, corporate bigwigs and other dignitaries prepare to meet in a sleepy Alpine corner of east Switzerland, there remains much to discuss and plenty to be done.

Internal conflicts

Just as last year’s forum was coming to a close, Donald Trump’s inauguration was getting underway. After his unexpected rise to become the leader of the free world on a tide of populist rhetoric, other political figures have sought to follow his path to power. In March and May respectively, the Dutch and the French went to the polls. Although Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen were ultimately defeated, it’s too early to announce the end of this populist wave.

In September’s federal election in Germany, Angela Merkel experienced the most disappointing of victories, with the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany party gaining 94 seats in the Bundestag. What’s more, populism is not always a minority phenomenon: the ruling party in Greece, Syriza, is a populist one, as is Hungary’s Fidesz. Populism can be found on both sides of the political spectrum but, no matter where it emerges, it poses a threat to liberal democracy and the existing global order.

Secession doesn’t simply damage the authority of national governments:

it also poses many economic questions

One of the most significant tasks facing WEF will be to reassert the benefits of globalisation. It has played a significant role in reducing poverty rates across the world, for example, but it has undoubtedly created losers as well. For many proponents of populism, ‘globalisation’ has become a dirty word. If WEF is to change this, it will also need to tackle its own image problem as a haven for the international elite: the ‘Davos Man’.

As countries have turned away from globalisation, they have invariably looked inwards, embracing protectionism and, notably, secession. In 2017, we saw the Catalan vote for independence act as a trigger point, but similar issues of autonomy remain unresolved in Scotland, Iraqi Kurdistan and elsewhere. Far from embracing greater collaboration with international neighbours, many nations are occupied with internal division.

Jason Sorens, a lecturer at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, believes each independence movement must be considered on its own merits, but also suggests there are some approaches that have historical evidence on their side: “What cannot be denied is that providing some kind of legal framework for independence – as the UK, former Czechoslovakia, Canada, Denmark and a few other countries have done – reduces political and economic instability and uncertainty, nearly eliminates the risk of violence and probably would not lead to widespread disintegration.”

Of course, secession doesn’t simply damage the authority of national governments: it also poses many economic questions. Looking at Catalonia, it remains unclear how the region would fare as an autonomous state. It may be one of Spain’s richest regions, but independence would see it automatically placed outside the European Union, with no guarantees it would be readmitted. As such, many businesses in the area have expressed concerns and some have already relocated.

Following the violent scenes witnessed in the disputed referendum and continued murmurings of other secession movements around the world, WEF’s task of bringing the world together doesn’t appear to be getting any easier.

Unequal innovation

One of the biggest talking points in the debate surrounding globalisation concerns technology and the role it is playing in connecting far-flung parts of the world. While improvements to transport infrastructure and the opening of states once belonging to the Soviet Union have exacerbated this trend, the proliferation of the internet has also made it much easier to trade services across borders. Since 1995, online usage worldwide has increased from 0.4 percent to 51.7 percent. Across the same period, trade as a percentage of global GDP has also grown by 15 percentage points.

The world is certainly a smaller place today, but whether it is a more equal one is less clear-cut. Globalisation, and the technology that facilitates it, has helped pull many citizens in developing countries like China and India out of poverty, but its reputation in the West is a lot murkier: the richest one percent now owns more than 50 percent of the world’s wealth, and income inequality levels are rising across OECD member states, even in traditionally egalitarian countries like Sweden and Norway.

One of the major tasks facing WEF will be addressing growing concerns that globalisation is resulting in a world of haves and have nots. Failure to do so will widen the vacuum in which divisive politics thrives. And yet, even as issues relating to globalisation continue to build, technology promises further anxieties in the not-too-distant future.

Implementing effective competition legislation without hindering innovation will be a key issue for WEF

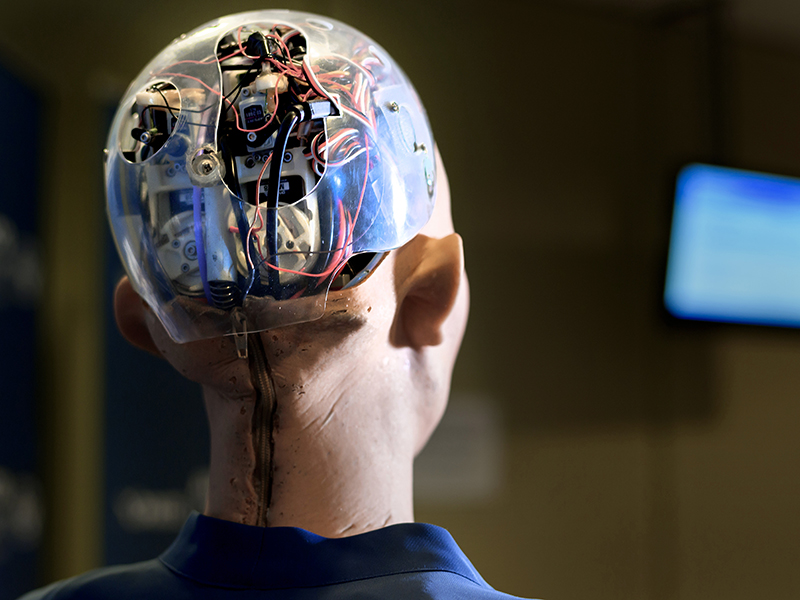

The fourth industrial revolution, or Industry 4.0, will prove truly transformative, with robotics and automation likely to create entire new industries while simultaneously disrupting many others. Improved efficiencies will generate huge profits for the businesses involved, but many employees are concerned that job losses are another inevitable consequence.

Automation is already used in various industries, but an additional 1.7 million robots are predicted to enter factories by 2020. Even though evidence suggests robots create more jobs than they destroy, this is unlikely to provide much consolation to the redundant machinist or train driver lacking in transferrable skills. Andrew D Maynard, Director of the Risk Innovation Lab at Arizona State University, believes the anxieties surrounding new technologies are understandable, particularly when they are likely to cause such radical change.

“Without responsible innovation, there is no guarantee that emerging technologies will decrease inequity and the gap between rich and poor, address challenges in a socially responsible way and ensure a better future for all,” Maynard said. “Rather, there is an increasing likelihood that technological innovations will lead to more problems than they solve, even with the best intentions.”

The way technology is concentrating wealth into the hands of a select few can also be witnessed through the growth of the so-called FANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google). These companies now hold so much sway over the digital economy that concerns have been raised about monopolistic practices and the impact this will ultimately have on consumers. Implementing effective competition legislation without hindering innovation, therefore, will be a key issue for WEF, as it always is when new technological solutions or business models are created.

The future of technological progress and the fate of globalisation are intertwined. If automation and other innovations can decrease inequality, then it is possible that citizens all over the world will grow to view globalisation as a process that celebrates our similarities and brings people from far-flung places closer together. If the gap between rich and poor continues to widen, a cultural and political backlash seems inevitable.

Climate consensus

The perennial issue of climate change is sure to be on the agenda at Davos this year. Arctic sea ice has shrunk by approximately four percent every decade since 1979, sea levels are rising at their fastest rate in more than 2,000 years, and the 21st century has seen temperature records broken with alarming regularity.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that something must be done, there remains little consensus as to what that should be. On June 1, 2017, US President Donald Trump withdrew his country’s support for the Paris Agreement on climate change mitigation. Trump’s decision may have scored points with his diehard supporters, but it prompted scorn from the rest of the developed world. Regardless of whether Trump’s move proves foolish or not, 2017 provided some stark reminders that time is running out for governments to pull together on the issue of climate change.

After it made landfall in late August, Hurricane Harvey resulted in 90 deaths and an estimated $198bn (€168.9bn) in damage. Hurricane Irma, which followed shortly after, caused further destruction across the US and Caribbean. These are the storms that stole the headlines in 2017, but there were many other natural disasters that inflicted devastation on a similar scale. One of the heaviest monsoons in recent years resulted in 1,200 deaths in India, Bangladesh and Nepal, while West and Central Africa was subjected to heavy flooding.

If the gap between rich and poor continues to widen, a cultural and political backlash seems inevitable

Michael E Mann, Director of the Earth System Science Centre at Pennsylvania State University, believes the damage caused by some of 2017’s storms was undoubtedly exacerbated by climate change. Higher temperatures and rising sea levels may not cause extreme weather events, but they certainly worsen their impacts.

“Climate change is the single greatest challenge we face as a civilisation,” Mann said. “The economic losses due to climate impacts and climate-change-exacerbated weather disasters is by some measure well over a trillion dollars in global GDP. According to one recent report, climate change over the next 10 years could cost the US as much as $360bn [€307.1bn] annually, nearly half of annual economic growth.”

As recent events remind us of the planet’s fragility, there remains optimism climate change can be halted, or even reversed. First, carbon dioxide levels remained flat between 2014 and 2016, suggesting emissions may have peaked. Second, China’s consumption of coal is declining, while its renewable energy sector thrives. The country’s government has also pledged to invest $360bn (€307.1bn) in renewables by 2020 and greatly reduce its reliance on fossil fuels.

In the fight against climate change, there are reasons to be both pessimistic and hopeful. An overwhelming 97 percent of peer-reviewed climate research papers indicate that human causes are to blame for global warming. Aside from a few stubborn naysayers, there is little doubt the planet has a problem. Whether the planet can work together to find a solution, however, is another matter.

Destructive forces

Attendees at January’s WEF are also likely to turn their attention to the various failed or fragile states generating instability in the wider world. The latter part of 2017 brought another refugee crisis, this time involving the Rohingya people of Myanmar. More than 500,000 individuals have fled the country for neighbouring Bangladesh, while the Myanmar military stands accused of a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” by the United Nations.

Although the plight of the Rohingya brought the suffering of refugees back into mainstream consciousness, they remain just one of the world’s many persecuted groups. According to estimates by human rights groups, the number of displaced people worldwide is in excess of 65 million. The problem is not helped by the fact 84 percent of these reside in developing countries.

Although it seems insensitive to talk about the financial implications of refugee crises when so many lives are being destroyed, the economic effects must be addressed. Improving the prospects of displaced people without placing undue burden on the states that take them in is a pressing concern for governments and charitable organisations all over the world. WEF has spoken previously about the importance of improving educational access for refugee children, but this will require long-term planning and investment.

According to estimates by human rights groups, the number

of displaced people worldwide is in excess of 65 million

Deep thought will also be required in Syria, where Islamic State is on the retreat but many other problems persist. The country remains deeply divided between those who are loyal to President Bashar al-Assad and those who believe he must be removed if the country is to have any chance of a stable future.

Although uplifting stories of Syrians rebuilding their homes and ways of life are becoming more commonplace, the country’s ongoing civil war will take years to recover from. The World Bank estimates the conflict has cost the country upwards of $226bn (€192.4bn), while many businesses have been destroyed and others have relocated to nearby regions, such as Turkey, Egypt and Jordan. The international community must decide how it can best support Syria as it attempts to heal division and repair its damaged economy.

WEF may also cast a glance at North Korea, which appeared hell-bent on causing as much disruption as possible in 2017. The year was punctuated by various illegal missile tests by the authoritarian regime in Pyongyang, including one in August that passed over Japan. With the war of words between Trump and North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un becoming increasingly heated, heads of state and financial markets will continue to watch developments very closely.

Work to do

The theme of this year’s WEF – ‘creating a shared future in a fractured world’ – recognises the global challenges presenting themselves today are as great as they have ever been. The political spectrum in many developed countries appears irreconcilably split, with little chance of compromise. Uncertainty is present in all corners of the world, whether it relates to North Korea, Donald Trump or Brexit.

While many countries appear politically divided, the economic situation does not look much better. If WEF is to truly encourage people to act together, it will need to convince many of them that billionaire CEOs and distinguished political leaders have the best interests of the common man at heart.

Looking back at more than 40 years of WEF, it is easy to be dismissive of its achievements, particularly when sifting through the various grandiose themes that have been chosen. The 2015 forum, for example, could hardly be described as creating a ‘new global context’, while the previous forum did not suddenly result in more responsive leadership.

Equally, this year is not going to result in mass global unity. WEF cannot solve the world of all its ills, but that isn’t really its aim. If even a single discussion leads to progress, then surely 2018’s forum will have been worthwhile.