Liberté, égalité, fraternité: the three words upon which the French Republic was founded. More than just a common philosophy, they are the ethos that built the French higher education system and the baccalauréat.

Introduced in 1808 by Napoleon Bonaparte, the baccalauréat (known informally as le bac) is an entrance examination that entitles those who pass to take a place at the French university of their choice. They can study any subject they wish – even without any prior knowledge. Given the tremendous stress many youngsters face trying to win a place at a top university and prove they have sufficient potential in their desired field, this characteristic of the French system is somewhat unusual, to say the least.

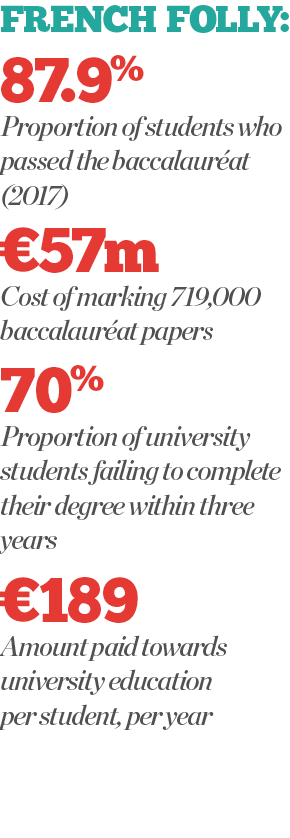

It used to make sense. Back in 19th-century France, few citizens were literate – and even fewer still were able to attempt the exam. In 1950, the proportion of students attempting Napoleon’s qualification had reached around five percent. But as aspirations and means developed, so did the desire to attend university: in 2017, approximately 87.9 percent of students passed le bac. And yet, the premise of Napoleon’s model has remained.

Universités surmenées

Unsurprisingly, this system – with its wholly good intentions – stopped working a long time ago. With the French Government covering the cost of university fees almost entirely – students paid just €189 each in 2017 – the state is coming under increasing pressure. Le bac alone is a great expense, with many students coming to regard it as their ‘given right’. This year, the cost of marking close to 719,000 papers came to a whopping €57m.

Universities are also struggling to cope. Each autumn, first-year students flood to their lecture halls in droves; designed for hundreds, they somehow squeeze in thousands. Deteriorating libraries are always overcrowded, while professors are simply unable to support such a large student body, particularly given their remarkably different needs.

Students who are markedly underprepared for the subject they have chosen soon suffer the reality of their choice. Many of them are simply unable to keep up, resulting in a high proportion of students dropping out after their first year. Others struggle on, retaking exams over and over again and wasting their own precious time and government resources as they refuse to admit defeat. Such is the case that, according to The Economist, over 70 percent of university students in France fail to complete their degree within the usual three-year period. The end result is disastrous for all parties involved.

However, France is finally on the cusp of changing this outdated system. Though not the first president to attempt to reform French higher education, Emmanuel Macron may be the last.

Bac to basics

France may be an extreme example, but it is one worth examining. The lesson to be learnt is that university education is not for everyone. But the trend of attending university almost by default has become prevalent across Europe: nowadays, many attend university simply because it is expected of them. Others go to put off the reality of working, enrolling for the fun and freedom it offers. But of course, there’s still a great number who attend to progress their careers.

With so many reasons to go, more and more people are studying at university level. The result, however, is fewer opportunities available upon graduation. Rewind 20 years and a good degree from a top university pretty much guaranteed a job upon completion. Unfortunately, these days, graduating is just half the struggle. With so many candidates, there are simply not enough graduate jobs to go around.

Lizzie Crowley, Skills Advisor at CIPD, a professional body for human resources and people development, said: “I think the assumption by getting more and more young people to go to university was that this itself would create a natural demand for those types of skills within business. But actually, the economy hasn’t changed at the same pace as the expansion of higher education.”

The result is a mismatch of skills. Overqualified graduates are turning to non-graduate roles, while those who would ordinarily be employed in such jobs are being outdone by the competition. As such, more young people feel obligated to go to university – further perpetuating this vicious cycle.

Degrees of debt

In the UK, a nation that boasts some of the best universities in the world, student fees have risen to around £9,000 (€10,165) a year for domestic students. In Sweden, the cost ranges between SEK 80,000 (€7,675) and SEK 270,000 (€25,906), depending on the subject. A private university in Spain, meanwhile, will set back students between €5,500 and €18,000 per year. Naturally, accommodation and living expenses present further costs. While other countries in Europe are cheaper, each year’s outlay still adds up to a considerable amount.

With so many university-educated candidates, there are not enough graduate jobs to go around

In addition to the direct costs of attending university, there is also the lost-opportunity cost of not working. This crucial three-year period (or quite likely longer, if you’re in France) could otherwise act as an instrumental step in one’s career progression, all the while allowing the individual to earn wages, rather than accumulate debt.

Aside from the obvious disadvantages of starting out with so much debt in tow, there is the question of what happens to these arrears when individuals aren’t able to repay – an unfortunate scenario for many graduates still searching for the type of job they studied for. Referring to the UK, Crowley told European CEO: “[Around] 75 percent of young people will never repay their student loans at all, because they’re not earning enough. So essentially, this is underwritten by the taxpayer.”

The apprentice

Though still disregarded by many at present, there is another way: apprenticeships. Learning while working boasts numerous advantages for young people, including the opportunity to gain real, hands-on experience, which is often the shortfall of graduates when searching for their first job. Crucially, it presents the chance to both earn money and avoid student debt.

“Apprenticeships increase the employability of young people,” said Hagen Krämer, Professor of Economics at Germany’s Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences. “Youngsters are confronted with [the] demands of the working world, i.e. they receive market-relevant training that improves their chances in the labour market.

“They get used to performing in the business environment, which is different to the school system in many ways. In addition, some young people who could not cope in a classroom [flourish] in a practical environment.”

Apprenticeships can also work exceedingly well for employers. “For companies, it is an ideal form of personnel recruitment,” Krämer explained. “They can gain two to three years of experience with the young people, [meaning] they know who they are dealing with and can avoid hiring the wrong people. Also, investment in first-class training is a key factor for success in an increasingly complex world. Digitalisation will further increase this need.”

As the benefits become more obvious, the range of available apprenticeships continues to broaden, creating a cycle of the more advantageous kind. Schemes are no longer restricted to manual trades and engineering; we are now seeing more apprenticeship opportunities in numerous other industries, such as publishing, IT, accountancy and journalism. With governments increasingly recognising the economic rewards – a more diversified workforce, less student debt and higher employment rates, to name but a few – they too are focusing on encouraging this shift.

The master

Generally speaking, the apprenticeship model is still underdeveloped in many countries in Europe. Germany, however, is in a league of its own. One of the reasons it has such a highly developed apprenticeship model is because of the country’s competitive manufacturing sector, which goes hand in hand with its strong export culture.

“The success of German export-orientated companies is based on high quality and technology, which requires a [medium-sized] and highly qualified workforce,” Krämer told European CEO. The German economic model, therefore, demands the skill sets developed by apprenticeships.

Germany’s three-year programmes involve a 50-50 split between classroom instruction in trade schools and on-the-job training with the help of skilled mentors at participating companies. By the end of the apprenticeship, individuals know a trade and how to perform it in a real-world environment.

The period of studying, and the level of education to which students reach, make Germany’s dual vocational education and training (VET) programmes equivalent – not inferior – to university qualifications. Seen in this way, it is unsurprising around 52 percent of young people in Germany complete a dual VET programme in their chosen field. Importantly, in the majority of cases, graduates of the programme are offered permanent employment at the company at which they were trained.

The success of this system speaks for itself. “Since the unemployment rate for 15-to-24-year-olds in Germany is below six percent – compared with over 15 percent across EU member states – an increasing number of countries are considering taking over the German dual-apprenticeship system,” said Krämer. “However, the question is whether the system can easily be transferred to countries with a different economic structure and a different system of industrial relations. I don’t think this can work anywhere.

Learning while working boasts numerous advantages for young people, including the opportunity to gain hands-on experience

“Transferring the dual-training system to another country is not easy, but generally not impossible. However, a transfer to another country will take time, as the system has a long tradition dating back to the Middle Ages. Many apprenticeships go back to the old guild system.”

As explained by Krämer, another reason the German model is so successful is simply because it has been around for so long. Young people are more open to it. It is seen as an excellent option for career progression after high school, not as a route taken by those ‘not smart enough’ to go to university – as is the common thinking in many countries.

Parents are also more encouraging of this step, knowing full well the benefits it offers, with many of them having travelled down the same road. And because apprenticeships are so respected in Germany, some of the biggest and most successful companies offer them, encouraging the brightest pupils to enrol.

What also sets the German model apart from other European states is that standardised training is offered, meaning apprentices can easily go on to work elsewhere upon graduation. Their new employer is confident in knowing the standard to which they have been trained, as well as what particular skills and knowledge they possess.

“Today, almost all companies in Germany require their applicants to standardise their vocational training, so that applicants trained for a particular profession have an advantage in the labour market,” Krämer told European CEO. “Most positions, from hairdresser to salesman, require standard training and certification.” Many apprenticeships in other nations offer training specific to the sponsoring company, making it more difficult for young people to gain employment elsewhere – a far less attractive option.

Transferring Germany’s system to another country will not be easy. It will require changing perceptions – a difficult feat in any area – as well as a great deal of support from a variety of stakeholders. “One challenge for a well-functioning dual-training system is that there must be close cooperation between government, business and the social partners,” Krämer said. Of course, as Krämer explained: “Other countries do not have to replicate every detail of the German system.” But what they can do is draw invaluable lessons and proof of the success an economy can have in supporting this pathway.

Degree or not degree

There is no denying the importance of university degrees: they open doors for individuals, revealing new possibilities and understanding. Degrees can enable students to really delve into a subject they are passionate about, all the while developing their analytical and writing skills in ways that will benefit them for the rest of their lives. Those who are unsure about their futures can also use this time to figure out what they want to pursue upon graduation.

This flexibility is possible because completing a degree involves the acquisition of certain skills – skills that are transferrable. For many jobs, the actual knowledge learned at university isn’t crucial, but the proof of certain skills, ambition and dedication is an ideal foundation for a whole host of careers. They tell an employer enough about a person to give them a chance to prove themselves in person.

When improperly leveraged, degrees are a waste of time, money, government resources and academic support

Social skills gained during university are another invaluable resource. During this time, many are given the chance to really develop as a person; to become and present to the world the person they want to be, free from teenage hang-ups and parental pressure.

They choose friends, rather than simply turning to those seated next to them in class. They pursue hobbies and extracurricular activities that help them develop further and broaden their horizons. And finally, they network; meeting like-minded people who may become business partners or key contacts in the years to come.

But certainly, degrees are not for everyone. For those who are in it just for fun, to delay reality or who want a job for which a degree isn’t actually required, they are a lost opportunity. When improperly leveraged, degrees are a waste of time, money, government resources and academic support. As such, the assumption that university is the next logical step for all is simply illogical.

This belief is what has got many Europeans into the predicament they currently find themselves in – indebted, unemployed and, when they do find a job, often overqualified. This is a scenario that can lead to ample stress and dissatisfaction. Their respective governments also feel the burden; through subsidising unnecessary degrees, the state is lumbered with unpaid loans and high youth unemployment rates. Employers, too, have to deal with unhappy and unproductive staff, which further exacerbates the negative economic impact of the situation.

For many young people, a degree may not be the wisest option, but an apprenticeship could be. As Germany demonstrates, with enough support from the government and the corporate world, apprenticeships are a wonderful route to take. They ease stress on the state and enable employers to thoroughly train new starters, who are given decent wages and employable skills in return. Studies also show apprentices have greater loyalty to the companies they trained with, having learned so much from them.

Macron is right to reform le bac. Under a well-intentioned guise of equality, it has let down too many for too long. But France is not alone in such mistakes, and our leaders of the future continue to suffer as a result. A change in mindset, however, can open up viable new options for young people, freeing them from the confines of university education. This, in turn, will allow individuals to choose the best possible path for them, in accordance with their unique skills, needs and dreams.

Ultimately, the well-executed provision of each route – degree qualifications and apprenticeships of an equivalent standard – is crucial for the future of our youth. If done correctly, it could foster an economy in which every person is best matched to their career of choice – rendering the debate of university education vs apprenticeships largely academic.