“We need to regain our future.” This rallying cry reverberated around Rome on October 12, 2018, as more than 3,000 students took to the streets to protest further cuts to Italy’s woefully underfunded education sector.

Students have recently elected deputy prime ministers Matteo Salvini and Luigi Di Maio to thank for the redistribution of desperately needed funds away from the schooling system. In an effort to deliver on ambitious campaign promises of increased welfare spending, the populist duo – who represent Lega Nord and the Five Star Movement respectively – have opted to increase the country’s budget deficit dramatically, which in turn has directed funds away from other areas, such as education.

Italy’s education sector has been on a financial roller coaster ride for the past few years. “In terms of expenditure, Italy experienced major cuts of almost €1bn per annum between 2010 and 2013,” explained Andrea Gavosto, a director at the education research foundation Fondazione Agnelli.

Education has never been at the top of Italy’s priority list, on a political or social level

“Then, when the Renzi government came in [2014], it pledged €3bn extra every year.” Now, this additional investment is set to be redirected to service a larger budget deficit, leaving the education sector gasping for air.

This is a particularly harsh blow for a country that already spends far less of its GDP on education than many other EU nations. Yet, with reports emerging of school buildings crumbling and establishments in Rome unable to provide pupils with toilet paper, it is clear additional funds are sorely needed.

Cutting class

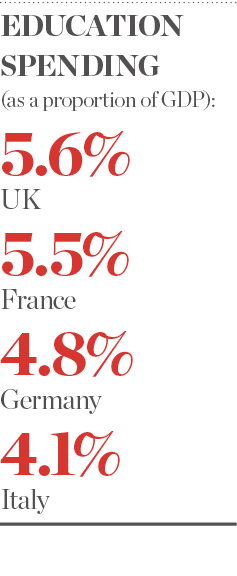

Italy has bucked the international trend with regards to education funding in recent years. Across the globe, spending rose from 3.9 percent of GDP in 2000 to 4.9 percent in 2015, the latest year for which the World Bank had data available. By contrast, Italy spent 4.3 percent of GDP on education in 2000, compared with 4.1 percent in 2015. It fares worse still when compared with other major European countries: in 2015, Germany spent 4.8 percent of its GDP on primary, secondary and higher education; France contributed 5.5 percent; and the UK 5.6 percent.

Gavosto told European CEO that most of the lag stems from university spending: “[Italy] spends about one percent of GDP on [universities], which is much lower than countries such as France, Germany and the UK – not to mention the Scandinavian countries, all of which spend between two and three percent.”

Education in Italy is compulsory between the ages of six and 17, after which pupils can choose whether or not to attend university (tertiary education). According to Eurostat, just 57 percent of Italians aged 25 and over had obtained a diploma at upper secondary or tertiary level in 2015, compared with 76.3 percent in the rest of the EU. Gavosto said this is due to the fact the drop-out rate in secondary and tertiary education is extremely high in Italy, particularly in the southern regions, where it can reach 20 percent – more than double the EU average.

“The government has made a major effort to bring… down [the drop-out rate] in recent years, and the national average is now 14 percent,” Gavosto said. “But it remains dangerously high on the two major islands and within the Calabria and Naples regions.” Those areas in particular have high numbers of pupils opting for vocational courses, rather than more traditional academic routes, which Gavosto described as being “extremely weak”.

Other EU countries, such as Switzerland and Germany, have very strong vocational offerings, as they recognise academia is not an appropriate path for every pupil, especially those seeking practically focused careers in industry. By contrast, the attitude in Italy is much more akin to ‘academia or the highway’, which results in many pupils simply giving up and leaving without a diploma.

This high drop-out rate has a significant impact on the composition of the workforce and unemployment levels among young people. “Italy has two million young people who are neither in education, training or jobs,” Gavosto explained. This equates to around three percent of the population who are of prime working age but aren’t contributing anything to the national economy.

What’s more, according to the European Commission, more than 90 percent of Italian SMEs are made up of fewer than 10 employees. This means companies often do not have the time nor the finances to invest in incoming employees – they simply expect them to be equipped with the appropriate skills. That’s hugely problematic given the fact that many young people are dropping out of school before the end of their studies. Those who do make it across the finishing line, meanwhile, are finding the skills they have aren’t adequate in the workplace.

“We clearly have a skills mismatch,” Gavosto said. “Technical vocational schools aren’t providing young people with the right skills for the right jobs, but firms are too small to spend time and resources on training them. The two sides of the market don’t match up at all.”

A crumbling facade

Protesting students argued that increased investment in the education system would help to combat the issue of dropouts. In a statement published on its website, Rete degli Studenti Medi, a student campaign network that played a significant role in orchestrating the October protests, said: “We are tired of paying hundreds of euros for our most important right: to study. Too many kids leave school because they can not afford it – it’s time to say enough.”

Unlike in other countries, state schools in Italy are not entirely free – there is a registration charge of approximately €20 to be paid per annum, while students are responsible for paying for textbooks and stationery, which can cost up to €400 each year for a child at upper secondary school.

Rete degli Studenti Medi also called for additional funding for school buildings: “We want safe and functional schools, not jails or ghettos.” Italian educational infrastructure has quite literally been left to crumble since many of the buildings were first built: the majority of school buildings were either erected during the early 1900s or in the 1960s to cope with the influx of new pupils born during the baby boom. Few have been structurally maintained, reinforced or repaired since construction, while many are woefully ill-equipped to cope with the demands of modern pupils.

If education is not being prioritised by politicians, it follows that society will cease to value it in the same way too

“Most of the infrastructure is totally inadequate from a didactic point of view,” Gavosto said. The age of buildings can also pose a serious safety risk: according to the Italian National Institute of Statistics, more than 156 school ceilings have collapsed in the past five years, with one student, 17-year-old Vito Scafidi, being killed in 2008.

Although infrastructure would certainly benefit from a funding boost, throwing money at the entire sector isn’t the answer. Rather, what’s needed is a comprehensive redistribution of existing funds, which are currently being funnelled to all the wrong places. According to Gavosto, more than 80 percent of the education budget is spent on teachers’ salaries, leaving little money for anything else. Italy has one of the highest teacher-pupil ratios in the EU, with an average of around 10 pupils per teacher across the country – and that’s just in state schools. Unfortunately, they’re not always hired for the right reasons, either.

“Schools are perceived by policymakers as a way to fight unemployment, and that has historically led to teachers being hired without having the right qualifications or the right motivations to do the job,” Gavosto said. It goes without saying that incorrectly trained educational staff cannot provide pupils with the best possible teaching; as a result, pupils often become disengaged, leave school and are later hired as teachers to bring down youth unemployment rates. It’s a vicious cycle.

The inefficient distribution of funds also leaves no budgetary room for investment in extracurricular activities. The majority of Italian schools – particularly those at primary level – are scraping by, providing basic education with little cultural enrichment. Although sport, music and art are technically part of the mandatory curriculum, a lack of funding means they are only taught for a few hours per week. There’s certainly no scope for trips to local museums or galleries, meaning pupils are missing out on key learning opportunities.

Further, schools don’t provide the option to participate in sports teams. As such, children are forced to join private, fee-paying associations to practise sports. This effectively reserves extracurricular activities for an elite class of pupils whose parents have the time, money and inclination to fund them.

Life lessons

Salvini and Di Maio’s decision to direct funds away from education in the 2019 budget despite these well-documented and enduring problems earned them a vitriolic response from the European Commission.

The duo originally wanted to increase the deficit to 2.4 percent of GDP, flouting EU regulations, but Brussels refused to accept such terms, with the European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Pierre Moscovici, suggesting such a large deficit would mean “one euro less [spent] on roads, one euro less on education and one euro less on social justice”. A 2.04 percent deficit was eventually agreed in December 2018 – a substantial increase on the 1.8 percent limit set by the previous government and one that is likely to prove just as troubling for the education sector.

Yet, while both protesting students and the European Commission have lambasted Salvini and Di Maio for the increased cuts, to attribute the blame solely to these two individuals is to disregard a significant element of the debate. Education has never been at the top of Italy’s priority list, on a political or social level – Italians simply do not valorise it in the same way other European citizens do. “[Education] is never a major topic during general elections or in party manifestos,” Gavosto said. “It’s always a side topic in the policy debate too, which is a pity.”

According to Gavosto, the rate of return in terms of wage growth on each additional year of education after high school is eight percent per annum: “Eight percent is a fantastic investment, much better than you can get from real estate or equity markets nowadays,” Gavosto said.

However compelling the data, it seems societal attitudes do not match up. According to 2017 statistics released by Eurostat, just 26.2 percent of Italians aged between 30 and 34 had completed a university degree, the second-lowest percentage of all EU countries. If education is not being prioritised by politicians, it follows that society will cease to value it in the same way too.

The devalorisation of education has trickle-down effects on other sectors as well. “When people are [better] educated, they are [healthier], they eat better, they look after themselves more, so it will help in terms of health spending if people are educated,” Gavosto said. “The [better] educated you are, the better citizen you are.”

It’s clear that inadequate education spending furnishes a country with a wealth of short and long-term issues, from safety concerns related to crumbling school buildings to rising youth unemployment. And yet, the knock-on effects of not investing in Italy’s youth doesn’t seem to have figured in the government’s consciousness when devising the new budget.

Salvini and Di Maio have failed to realise that the increased welfare spending they are proposing wouldn’t be necessary if they put the onus on education now. With their current strategy, they are likely to find that today’s undereducated, underemployed youth will need even more welfare support when they reach retirement age. And when today’s students come knocking in five, 10 or even 20 years’ time, they will find the pot is empty.