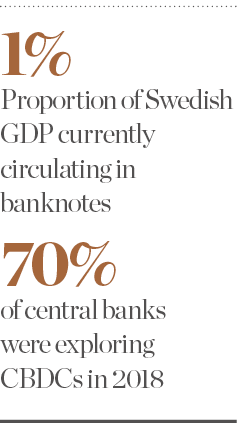

Few countries have embraced the drive towards a cashless society with as much enthusiasm as Sweden – only one percent of Sweden’s GDP currently circulates in banknotes, making it one of the least cash-dependent countries in the world. It’s only appropriate, then, that the Scandinavian country could soon become the first nation to release a central bank digital currency (CBDC). In February, the Riksbank announced it had begun testing a digital version of the krona – the e-krona – by simulating its use in everyday banking activities.

Sweden’s interest in CBDCs is not unique: governments around the world are closely examining the potential benefits of implementing a digital currency. According to a report published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) last year, 70 percent of central banks were exploring the technology in 2018. There are a host of possible advantages to issuing a digital currency, but critics warn that central banks shouldn’t overlook the inherent risks.

The rise of CBDCs

Central banks’ interest in CBDCs was partly sparked by the prospective launch of Libra, a digital currency put forward by social media giant Facebook. Many fear the introduction of such a currency would undermine central banks’ control over money creation, and have started exploring alternative digital solutions in response.

At the current stage of testing, central banks must heed the risks that CBDCs carry

Indeed, the Riksbank has said the issuance of a digital currency could “reduce the risk of the krona’s position being weakened by competing private currency alternatives”. Given how rapidly the Swedes are forgoing cash for digital alternatives, such a risk is very real. According to a study conducted by Niklas Arvidsson and Jonas Hedman, researchers at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Copenhagen Business School respectively, Swedish retailers could stop accepting cash as early as 2023.

Central banks also believe that CBDCs could make payment systems more efficient and cost-effective. Unlike cryptocurrencies, CBDCs are distributed by an authority (the central bank) and not by decentralised online communities. Like cryptocurrencies, though, they are based on blockchain technology, meaning they could prove much more streamlined than the current payment infrastructure.

There are other advantages, too. “One of the main benefits is that a basic-service CBDC can act as a competitive check against the pricing power that large banks and other payment processors have in oligopolistic settings,” David Andolfatto, Senior Vice President (Research) at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, told European CEO. “A CBDC that coexists with an alternative payment system [operated] by a private consortium of banks would also be useful as a backup, as the two systems could back each other up should one of them experience a temporary disruption.”

Sweden’s predominantly cashless society gives it a greater incentive than most to issue a digital currency, but there are concerns that CBDCs could spell bad news for financial inclusion. As Ola Nilsson, a specialist in consumer policy at the Swedish National Pensioners’ Organisation, explained to European CEO, Sweden’s cashless society has disadvantaged those who live in rural areas, the disabled and the elderly.

He said: “Although there are many older people in Sweden [who] have used digital payments for years, there [is] still a large group that’s not there yet. They are unable to do things in everyday life that they have always managed before – things like buying a ticket for the bus or train, using public toilets or paying for car parking. The opportunity to pay with cash for a coffee at a cafe or lunch at a restaurant can no longer be taken for granted.”

The other side of the coin

Some nations remain unconvinced that CBDCs are worth the trouble. After testing a CBDC in 2018, the National Bank of Ukraine concluded that it didn’t see any real advantage in issuing a digital currency. In fact, it later warned that CBDCs could pose a threat to the financial system: “The banking system may cease to be a major financial intermediary if the majority of the population switches to using the central bank’s digital currency instead of cash and bank accounts.”

Indeed, there are risks beyond financial inclusion: in a recent quarterly review, the BIS highlighted consumers’ tendency to convert electronic holdings into cash in times of financial turmoil. “The main concern is that if, in the future, cash were no longer generally accepted, a severe financial crisis might create further havoc by disrupting day-to-day business and retail transactions,” it wrote. Currently, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency advises everyone to keep cash at home in small denominations in case the payment system crashes. Some experts argue that Sweden should avoid a full transition to the e-krona for this same reason – the Riksbank has previously said the e-krona would complement, rather than replace, cash.

Critics of CBDCs suggest they could pose a threat to citizens’ privacy when deployed by authoritarian governments. China is hot on Sweden’s heels in the race to create the world’s first CBDC, with four of its largest banks launching internal tests of the technology in April. But while many Chinese consumers already pay for goods using apps that are linked to their bank accounts, such as WeChat or Alipay, a state-operated payments system would enable the government to track all of its citizens’ purchases.

Nonetheless, Andolfatto believes that, when CBDCs are used correctly, the benefits far outweigh the risks. He told European CEO: “There are risks only to the extent the power is misused. Otherwise, a well-designed and well-regulated CBDC would, in my view, enhance all interests in society.”

Euro vision

The Riksbank expects its e-krona pilot to end in February 2021. Depending on the project’s success, more tests will then follow, meaning it will still be several years before the world’s first CBDC is released. Crucially, though, it’s no longer a question of if governments will introduce CBDCs, but when. The Bank of France has put out a call for applications from firms interested in experimenting with the use of a digital euro for interbank settlements, while the Dutch central bank has announced that it wants to play a “leading role” in the research and development of both its own CBDC and a digital euro.

At the current stage of testing and development, central banks must heed the possible risks that CBDCs carry. In 2019, an independent report funded by LINK, the UK’s largest cash network, used Sweden as an example of the “dangers of sleepwalking into a cashless society”. However, as Nilsson pointed out, the e-krona need not exclude vulnerable groups unless it’s developed without these segments of society in mind. “We think it is important that the design of digital payment methods… be adapted so that all target groups in society can use it,” he said. “Accessibility and simplicity are important. I think that the Riksbank has a possibility to create something we all can use in our everyday life in the future.”

A cashless society is, in many ways, a more convenient one, but only if the payments system is built with everyone in mind. In developing CBDCs, central banks will play a key role in determining what a cashless future will look like, but careful planning is needed to ensure it strengthens trust in the financial system, rather than weakening it.