Taxes are said to be one of life’s two certainties. They provide a vital contribution to state revenues and can help discourage citizens from doing harmful things, like smoking or eating too much junk food. When implemented overzealously, though, taxation can have

unintended consequences.

One supposed drawback is that when taxes are too high, they suppress entrepreneurialism, taking money away from private innovators and locking it up in public coffers instead. In the US – a society that is broadly tax-averse and home to world-changing companies like Apple and Amazon – such a view is a popular one.

Individualism is secondary to collectivism in Scandinavia, meaning that entrepreneurial communities are commonplace

However, this connection between taxation and innovation doesn’t seem to hold true everywhere: the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark are regularly ranked among the best places in the world to start a new business despite their high-tax environments. Well-known businesses Spotify, Just Eat and airline Norwegian have all emerged from this part of the world to international success.

Somehow, these small, Northern European nations have managed to pursue large income redistribution without disincentivising hard work and corporate invention. While this doesn’t necessarily mean that implementing similar tax policies outside of Scandinavia will bring success, it does suggest there’s more than one way of doing business.

Brass tacks

The assertion often thrown around is that the more individualistic Anglophone world views taxation as a burden, while the social democracies of Scandinavia are happy to contribute towards the greater good. The reality is more nuanced.

Corporation tax, for example, is relatively low in Scandinavia, and has been falling in recent years. In Denmark, it has declined from 50 percent in 1985 to 22 percent today. In Norway, it stands at 24 percent, and Sweden’s corporate income tax rate is set to fall to 20.6 percent by January 2021. These figures are competitive with the EU average (21.3 percent) and, indeed, most other developed economies.

There are good reasons for Scandinavia cutting business rates in this way. A recent research paper by Canadian think tank MEI, titled Entrepreneurship and Fiscal Policy: How Taxes Affect Entrepreneurial Activity, examined taxes across 85 different countries and found that a 10-percentage-point increase in corporation tax reduced the number of businesses per 100 people by 1.9. Further, it’s not necessarily true that cutting corporate tax rates diminishes overall tax receipts. Evidently, the approaches taken by Norway, Sweden and Denmark are not ideologically wedded to high rates of taxation and, instead, form part of a broader pragmatic, pro-business stance.

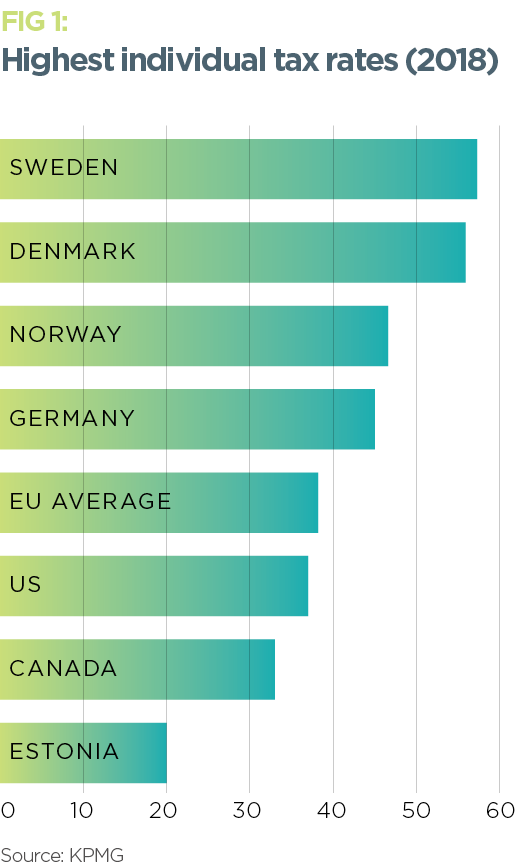

It must be said, however, that Scandinavian countries do impose a high personal tax burden on their citizens. When local and national rates are combined, Swedes earning above SEK 662,300 (€63,717) face a 57 percent income tax (see Fig 1). High earners in Denmark can also expect more than half of their pay cheque to go to the government, while the highest bracket in Norway stands at 46.6 percent.

Taxes in Sweden, Norway and Denmark are progressive, but they are also flatter than in most other nations. In Denmark, for example, the top marginal tax rate is applied to all earnings more than 1.2 times the national average income. By comparison, the top marginal tax rate in the US is only applied to incomes that are 8.5 times the national average.

The high rates of taxation experienced by Scandinavian citizens are repaid in the form of personal support structures; there is a long loop of taxation returning as ‘soft money’, which then feeds the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

“In Scandinavia, there is a ‘flexicurity system’,” explained Svein Berg, Managing Director of Nordic Innovation. “This means that although your company might fail, you will still have access to the welfare state. Consequently, the downside of becoming an entrepreneur is lower in the region than in other parts of the world. You don’t have to risk your entire future – you will still have food on the table even if you fail.”

Taxes in Scandinavia are not particularly high for businesses or those struggling to make ends meet, but when looked at across the whole country, they do constitute a significant proportion of government funds. Nevertheless, the region is rightly regarded as one of the most business-friendly in the world.

Starting off on the right foot

Ensuring that taxes in Sweden, Norway and Denmark continue to support the countries’ extensive social security systems without hurting domestic businesses is a difficult balancing act. It is particularly challenging when it concerns companies that are only just starting out.

Start-ups have a notoriously low likelihood of success – estimated failure rates typically range between 50 and 90 percent – and high taxes present an extra hurdle. Not only do taxes eat into young companies’ already tight supplies of capital, they also diminish the amount of potential investment available to them. And yet, Scandinavian start-ups are flourishing, emphasised by the huge exits of Swedish companies Spotify and iZettle in early 2018.

It’s not only multibillion-euro firms that are prospering in the region, either. In 2017, a total of 120 Swedish companies registered exits – the most recorded by any European country. Denmark, meanwhile, boasts the continent’s largest network of support programmes for tech start-ups, and the Norwegian Government’s innovation fund distributed NOK 2.3bn (€242m) to entrepreneurs and start-ups in 2017.

In Scandinavia, entrepreneurs are given the confidence to attempt bold and risky ideas, safe in the knowledge that the welfare state will ensure they do not end up starving or homeless

While the taxes in these countries are substantial, it’s clear the level of support offered to young businesses is too. In particular, acquiring funding is relatively straightforward: a stable political environment, combined with a prosperous and well-educated workforce, means that both domestic and international investors feel confident of returns when backing new ideas.

The aforementioned government support is also robust. Tax breaks to help with investment, R&D and export costs are common across Scandinavia. Innovation Norway, in partnership with the Research Council of Norway, grants tax credits to approved projects, with extra support given to SMEs. Sweden has a liberal attitude towards foreign investment and, in Denmark, a new tax package improving the conditions for equity investments was announced in late 2017. The high taxes faced by the people of Scandinavia, it seems, are structured in a way that ensures entrepreneurial financing is not overly difficult.

“Securing funding in Scandinavia is seldom a challenge for a start-up that is innovative, ready and able,” explained Marwan Ayache, Head of Operations at the Stockholm School of Entrepreneurship. “Typically, the main challenges are building a team and transitioning seamlessly from prototype mode, through growth mode [and] into profitability.”

On a personal level, taxes in Scandinavia create a safety net that makes starting a new business easier. Entrepreneurs are given the confidence to attempt bold and risky ideas, safe in the knowledge that the welfare state will ensure they do not end up starving or homeless. This social contract provides a springboard for game-changing companies, particularly those in the technology sector.

Give and take

As well as making sure the high rates of taxation do not overly burden new businesses, the respective governments of Sweden, Denmark and Norway have implemented other measures to encourage entrepreneurialism. The Swedish Government, for example, subsidised the purchase of personal computers in the 1990s, laying the foundations for today’s tech-savvy society. Similar digital growth strategies have been employed in Denmark and Norway, too.

“Historically, Sweden (specifically Stockholm) has experienced a series of fortunate events leading to engineering and design accomplishments that have, in turn, enabled it to embrace new technologies,” Ayache told European CEO.

“In the 1980s, the government spread dark fibre throughout Stockholm; today, the majority of homes and businesses are eligible for gigabit Ethernet via optic cables. In the 1990s, the government subsidised PCs so that the middle class could afford computers at home. This means that today, everyone under the age of 30 has grown up with a PC and is computer literate.”

A strong incubator network is also present across all three countries, providing new businesses with financial and technical support. These start-up hubs receive a mix of public and private funding, and often work alongside universities and municipal authorities to ensure they have a regional focus. Together with Scandinavian success stories like Spotify, they help to reinforce the region’s business-friendly reputation.

Still, the budding entrepreneurs of Sweden, Denmark and Norway are not all waiting in line for government support: help also comes in the form of a deeply embedded culture of collaboration. Individualism is secondary to collectivism in Scandinavia, meaning that entrepreneurial communities – and the support they provide to new businesses – are commonplace, particularly in the cities of Stockholm and Copenhagen.

Although originally intended as satire, the ‘Law of Jante’ – the hyperbolic code of conduct supposedly common to Nordic countries – has come to exemplify the cultural standards that dominate this particular part of Northern Europe. Broadly speaking, Scandinavians believe in a social code that encourages group behaviour and collective harmony. It makes team building easy and encourages a flat management structure that empowers employees at all levels to work towards a common goal – turning start-ups into long-term successes.

Playing it safe

Cultural norms in Scandinavia that value the collective over the individual may help entrepreneurs to find support, but they have drawbacks, too. A predilection for conformity and a suspicion of success can easily emerge, which helps to explain why entrepreneurialism and risk-taking have only recently started to gain wider acceptance in Scandinavian countries.

Entrepreneurial tradition is not particularly strong in the region and, even with a growing contingent of internationally successful firms, citizens can struggle to embrace the individualism required for business growth. In fact, Sweden ranked 50th of 54 countries for self-perceived entrepreneurial capability in the most recent Global Entrepreneurship Monitor study.

There are mounting challenges that look likely to increase the strain on Scandinavia’s economic model, including rising inequality and slowing productivity

Perhaps one of the reasons Swedes fail to fully appreciate their entrepreneurial capacity is that while the country provides fertile ground for companies to find their feet, high levels of growth are less easily achieved. This stems, in part, from a cultural aversion to risk, meaning that acquiring the extra investment needed to scale can prove problematic.

Attracting venture capital can also be difficult, particularly from international investors. Of the three countries, it’s only in Sweden that the primary source of investment comes from abroad. Accelerator networks are also less developed in Scandinavia, with Copenhagen’s Accelerace the only programme in the region to be consistently named among Europe’s best.

There are mounting challenges that look likely to increase the strain on Scandinavia’s economic model too, including rising inequality and slowing productivity. The immigration debate may also threaten the sustainability of the three countries’ approaches. Restricting the number of people coming into the region may be politically popular, but it could throw up issues for businesses. In 2015, Nordic entrepreneurs cited difficulties in locating and recruiting skilled staff as their main challenge. Stronger borders may make this more difficult still.

“Talent is definitely a pain point for the start-up ecosystem in Scandinavian countries,” Ayache said. “Start-ups need talent from abroad to meet hiring demand. Restricting immigration would not be good for building great teams, businesses or overall economic development.”

Although the likes of Sweden, Denmark and Norway are often lauded for their robust social welfare models, it is important that these countries are not romanticised: their domestic business environments have challenges of their own. And while many company owners are happy to pay high taxes, some believe that a reduction in government spending would benefit entrepreneurialism.

The right fit

It would be an oversimplification to say the Scandinavian approach to business is one that should be copied the world over. In fact, there are specific cultural and social factors that explain why the Scandinavian model of high taxation has proven so successful. Sweden, Denmark and Norway are small, largely homogenous countries, which helps breed a close feeling of trust between members of the community. This trust even extends to the government.

A 2016 survey conducted by Sifo, a Swedish market research firm, showed that members of the public have broadly positive views of the Swedish Tax Agency, often praising its public service and contribution to society. By contrast, a survey taken in the US at around the same time showed that more than 50 percent of Americans held an unfavourable opinion of their own tax-collecting body, the Internal Revenue Service.

“The combination of high taxes and high productivity is not developed overnight – it takes generations,” Berg explained. “When you pay high taxes and you see that you get free medicine, free healthcare [and] free higher education, it is easy to see the value you get back. People in Scandinavia perceive that their governments are honest, hard-working and trying to do their best for the population. People accept high taxes because they trust politicians to do their utmost to ensure that the money is spent in a way that is beneficial to the entire population.”

As well as forcing businesses to consider internationalisation from the outset, the Scandinavian countries’ small populations make it easier to have a transparent system of taxation. In other words, the gap between politicians and the public is smaller than would be possible in a country like the US. This ensures there is more accountability, making high tax rates more palatable for both employees and employers.

While the cases of Sweden, Denmark and Norway demonstrate that high taxes do not necessarily kill innovation, it should be noted that these countries have moved towards a greater degree of market liberalisation in recent times. Taxes remain higher than in, say, the UK or the US, but they are falling. In Denmark, for example, the personal income tax rate was cut by more than six percent in 2010, meaning today it is close to its record low.

Aside from rates of taxation, other workplace norms are important. According to the latest OECD findings, people in Denmark devote 66 percent of their day – 15.9 hours – to personal care and leisure. Presenteeism is not such an issue in Scandinavian nations and, as such, the amount of free time enjoyed by staff is greater than most. This freedom is good for employee wellbeing: Sweden, Denmark and Norway are often ranked among the happiest countries in the world. Evidently, it is good for entrepreneurialism, too.

While tax policies can always be more business-friendly, most Scandinavian citizens appear happy to pay a little extra compared with those in the Anglophone world – whether they’ve launched their own business or are working their way up the corporate ladder. Taxation may be inevitable, but its impact on innovation doesn’t have to be.