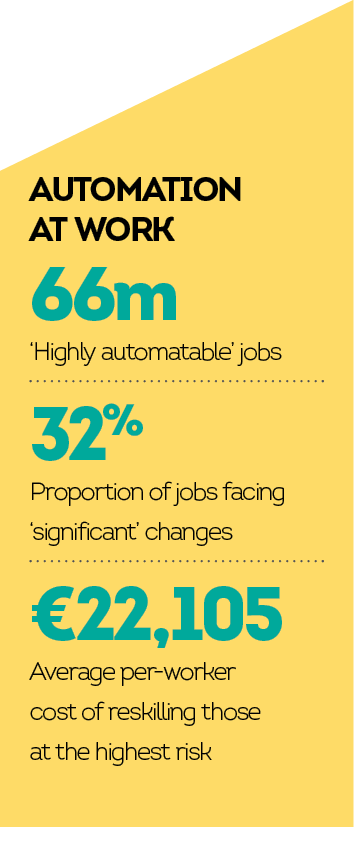

Around the world, approximately 66 million workers are at a high risk of being displaced by automation and artificial intelligence (AI) in the coming years, a 2018 report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found. This ‘highly automatable’ category represents around 14 percent of jobs in the 32 developed countries involved in the study, with another 32 percent set to face ‘significant’ changes due to automation. Taken together, this means nearly half of the global workforce will be impacted by the adoption of new machine-learning technologies.

Automation has undeniably provided businesses with numerous benefits, from improving efficiency to cutting costs. It is now apparent, though, that without the right precautions in place, replacing humans with robots will exacerbate a growing skills crisis and result in mass technological unemployment. Reskilling programmes, while costly, will be essential in helping close the skills gap and ensuring at-risk employees are not left behind.

AI for an eye

Fortunately, there is still much that machines cannot do. Recreational therapists, mechanical supervisors and social workers, for example, were highlighted as having a very low chance of being replaced by automation in a 2013 paper entitled The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?

Executives are increasingly realising the looming skills crisis requires urgent action

The report, which was written by University of Oxford researchers Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, and has subsequently been built upon by organisations such as the OECD and willrobotstakemyjob.com, outlined three skills that cannot be easily automated: creative intelligence, such as improvisation or problem-solving; social intelligence, including situational judgement or care and emotional support; and the perception and manipulation of the world around us, such as a sense of time and space.

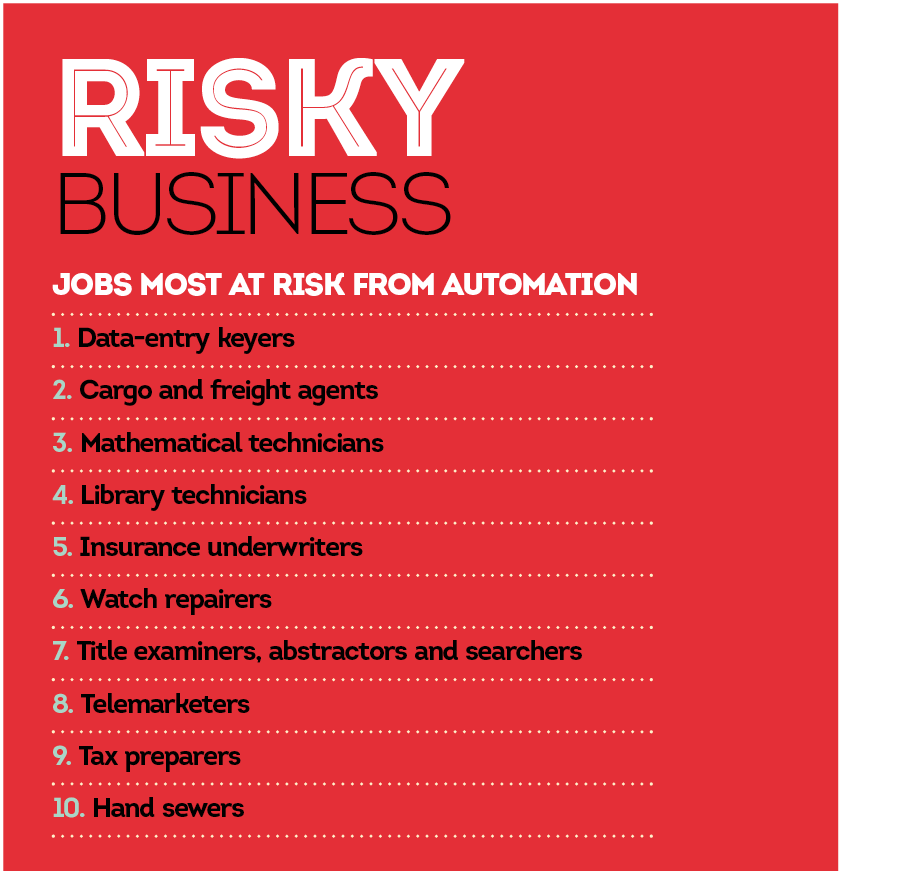

However, Frey and Osborne also predicted that 47 percent of all US jobs were at a high risk of being handed over to AI in the next decade or two. According to the OECD, the jobs with the highest probability of replacement involve routine tasks and low skill requirements, including manufacturing, agriculture and some service jobs. But the widespread nature of technological advances means numerous sectors – from finance to medicine – face some level of disruption.

The highly educated are not immune, either. In fact, Ed Abbo, President of C3.ai, an enterprise AI software and development company, told European CEO that even the most intelligent individuals will have to spend “a significant amount of time investing in continuous education”. According to Abbo, reskilling poses a “daunting” challenge to employers, but executives are increasingly realising that this looming crisis requires urgent action. What’s more, he believes business leaders have an acute level of awareness when it comes to the complex web of issues presented by automation.

For instance, a 2017 survey by management consultancy McKinsey & Company found that 62 percent of executives at large companies believe they will have to retrain or replace more than a quarter of their workforce between now and 2023 due to advances in automation. Technology consultants at Gartner, meanwhile, estimated that 64 percent of managers don’t think their employees will be able to keep pace with future skills needs. Strikingly, only 20 percent of employees were found to have the skills they needed for their current job and future career.

“The real value from automation comes from augmenting human productivity with technology – not replacing humans,” Jonathan Wyatt, Managing Director and Global Head of Digital at consulting firm Protiviti, told European CEO. “To succeed in the digital age and to achieve this vision, you need a digitally literate workforce.”

Old dogs, new tricks

Retraining workers would help to manage both the widening skills gap and the imminent advances in robotics, but it is a complex and expensive task. “Whether workers lose their job as a result of automation or have to adapt to new tasks and job content, the challenge for adult learning systems is considerable,” the OECD report said.

Ensuring that retraining programmes reach the people who need them most will be key. For instance, the OECD found that lower-skilled and younger workers would be disproportionately affected by automation displacement. Older workers, meanwhile, would face “more difficult transitions”, due to having lower participation rates in adult learning programmes.

Across OECD countries, around 40 percent of workers currently participate in job-related training, but this varies considerably from one country and socioeconomic group to another: on average, only 17 percent of low-skilled workers across these countries received training. “The training challenge is amplified by the fact that the risk of automation [is] not distributed equally among workers, making existing differences in access to training even more problematic,” the OECD report said.

Directing training programmes towards the right people is not the only implementation challenge: they also come with a huge price tag. In the report Towards a Reskilling Revolution: Industry-led Action for the Future of Work, researchers from the World Economic Forum (WEF) concluded that it would cost around $34bn (€30.31bn) to reskill the 1.44 million US workers at the highest risk of losing their jobs to automation within the next decade. That works out, on average, to approximately $24,800 (€22,105) per worker.

All of these hurdles have kept many organisations from establishing retraining initiatives. According to the WEF’s report: “A large percentage of companies across most industries still have not made significant investments in reskilling and upskilling programmes.” Instead, many are searching for new employees who already have the skills they need. “The majority of organisations are focusing on recruitment and replacement as the primary means of developing new competencies with the assumption that corporate knowledge is easier to learn than new capabilities,” Wyatt said. “This assumption may not necessarily be true.”

Reskilling programmes offer a critical route for transitioning through the technological revolution

In fact, the WEF found that there is a “compelling financial and non-financial business case for companies and governments to reskill at-risk workers”. Of the 1.44 million US workers expected to be displaced by automation in the coming decade, the WEF estimated that 95.3 percent could be transitioned into new positions with similar skills and, in some cases, higher wages. The report recommended companies take a three-pronged approach to investment in order to prepare for both the short and long-term implications of automation: reskilling at-risk workers, upskilling the broader workforce, and building an environment for continuous learning within the business.

In good company

One incentive employers have for investing in retraining programmes is the risk of losing unengaged employees. This is due to the fact that reskilling opportunities are highly sought after by workers: as Boston Consulting Group (BCG) found in its Decoding Global Talent 2018 report, employees and jobseekers often value learning and training opportunities above job security, financial compensation and completing interesting work in their day-to-day job.

“An engaged workforce is crucial in order for the digital transformation of the business to happen,” Wyatt said. “The most significant cost [of] not upskilling your workforce is the inevitable slow decline of the business as it loses market share or suffers a squeeze on margins if it is not able to take advantage of the latest technological advancements.”

A number of companies have taken the plunge to establish their own reskilling schemes. Retail giant Walmart’s programme, the Walmart Academy, was launched in 2016 and had trained 720,000 associates in advanced retail skills, leadership and change management by the end of 2018. Abbo said there are other companies taking a very proactive and effective approach to reskilling. For example, he cited a handful of C3.ai’s energy and utility clients across Europe – including Royal Dutch Shell, Enel and ENGIE – as some of the firms that are successfully reshaping their workforces as they adopt new technologies.

Sweden’s job security councils are another positive example. The councils, which are established through collective agreements and financed by employers, aim to ensure displaced workers are assisted in adapting to new situations and do not become demoralised, according to a report on the programme published by the OECD. The schemes help both white and blue-collar workers by providing guidance to jobseekers, as well as offering consultation to employers and trade unions, and delivering tailored transition services.

As a result, Sweden has the highest rate of re-employment in the OECD, with around 85 percent of displaced workers finding themselves re-employed within a year. But while the OECD concluded that the “unique Swedish model works well”, it is not easily replicable in many other countries because it is facilitated by a “long-standing tradition of collaboration between the social partners to share responsibility for restructuring”.

State champions

Although the Swedish Government has remained largely absent in legislating for displaced workers, other countries’ policymakers are leading the charge on reskilling. In France, for example, employees over the age of 16 are given easier access to gaining new skills through personal training accounts, known as compte personnel de formation (CPF). Through these accounts, workers accrue hours to use on training courses with guaranteed paid leave from work.

According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, nearly 500,000 requests to use CPF hours were approved in 2016, up 139 percent from the previous year. Of these, 65 percent came from jobseekers and 35 percent came from employed workers. The most popular courses included exams to acquire language and information technology (IT) certificates.

Singapore’s SkillsFuture initiative, meanwhile, aims to develop an education and training system for every citizen – no matter how old – that will foster a culture of lifelong learning. The programme, which is overseen by the government’s Future Economy Council, offers citizens over the age of 25 a credit worth SGD 500 (€327.63) to use for a wide variety of training courses. Those over the age of 40 can also receive subsidies of up to 90 percent on training costs. As the SkillsFuture website puts it: “Skills mastery is more than having the right paper qualifications and being good at what you do currently – it is a mindset of continually striving towards greater excellence through knowledge, application and experience.”

According to The Straits Times, Singapore’s small and medium-sized enterprises have been eligible to apply for a SkillsFuture grant worth up to SGD 10,000 (€6,553) to cover the majority of the cost of training employees since July 1, 2019. The subsidy could reduce the cost of sending an employee on a training course from SGD 2,000 (€1,311) to SGD 60 (€39.31), the newspaper calculated. According to its own research, in 2018, about 465,000 Singaporeans and 12,000 enterprises benefitted from SkillsFuture training subsidies.

Skills that pay the bills

Despite these signs of encouragement, too many businesses still fail to make reskilling a priority. “For a lot of organisations out there, [retraining is] an expense that is the first thing to get cut when a squeeze hits,” said Rod Flavell, founder and CEO of FDM Group, an international professional services company that trains graduates, individuals who have taken a gap in their career and ex-military personnel as consultants.

Yet the benefits of reskilling are clear. The WEF found that it is in the financial interest of businesses to take on part of the cost of reskilling, with a $4.7bn (€4.19bn) investment from the private sector capable of reskilling a quarter of all US workers in disrupted jobs at a profit.

Significantly, however, even more workers could be reskilled with a positive cost-benefit balance if the public and private sectors were to team up. The WEF report said: “We find that this balance sheet could be significantly extended further through public-private collaboration, such as a pooling of resources or combining of similar reskilling efforts, leading to economies of scale and lowering reskilling costs and times.”

In fact, the WEF found that nearly half of the at-risk workforce could be profitably reskilled by businesses if employer-led efforts improved cost and time efficiency by 30 percent. Furthermore, a $19.9bn (€17.7bn) investment by the government could reskill 77 percent of workers while generating a positive return in the form of tax gains and lower welfare payments.

Adapt or die

The transformation of the workforce doesn’t just require employees to learn new skills, though: it also compels individuals to adopt a new mentality towards work and their career. This will require workers to accept a degree of responsibility. As BCG’s report said: “For individuals, the best advice is probably not to bet everything on one skill. Indeed, workers should understand that skills that once seemed like a guarantee of lifetime employment can lose their relevance quickly.”

Arguably the most important skill moving forward will be the ability to adapt to new environments and learn continually

Although it is impossible to predict what the future of work will look like, it is doubtless that technical skills will play an important role. “There will be a significant demand for individuals with some level of software development capability,” Wyatt said. Expertise in cloud software, cybersecurity, intelligent automation and data science will be in demand.

However, there will also be a strong need for non-technical skills. “There will be significant focus on innovation… and creativity, design thinking, facilitation and change management skills,” Wyatt predicted. “There will also be demand for the evangelists [and] communicators who can create excitement and articulate the organisation’s transformation journey.”

The WEF report predicted that some of the most important skills in the future will include technology design and programming, creativity, initiative, critical thinking, leadership and emotional intelligence. Those talents facing growing irrelevance, meanwhile, included physical skills, such as manual dexterity, endurance and precision, and some mental skills, including memory, speech abilities and quality control.

Arguably the most important skill moving forward will be the ability to adapt to new environments and learn continually throughout one’s career. A collaborative effort from businesses, governments and individuals will be needed to embrace such a learning culture. As Wyatt said: “When it comes to training, the key is to inspire people to want to be a part of the future.”

This future may appear intimidating, but Flavell is optimistic about the coming changes: “I come from an area of the UK called the Black Country, which was the heart of the original Industrial Revolution.” While the decline of the UK’s mining and steel industries “decimated” his hometown, Flavell said the area had “reinvented itself” around light industry and services in the years since. “It had to find a different route forward,” he said. “And, being an optimist, I feel that society will find a route forward [through today’s challenges].”

Despite their costs and complexities, reskilling programmes offer a critical route for transitioning through the coming technological revolution. Ensuring these initiatives receive the investment they require and reach the people who need them most will take a concerted effort from every party involved. With successful retraining programmes in place, however, organisations can guarantee their employees will continue to have a valuable role to play in the future workplace.