If Europe were a car, Germany would be its engine. The continent’s largest economy is powerful, streamlined and highly efficient – just like the five million vehicles its formidable automotive industry churns out every year. Thanks to its export-driven model, low unemployment and robust policy environment, Germany has been able to emerge relatively unscathed from the financial storms that have dogged Europe over the past decade.

In 2009, while other nations floundered in the global financial crisis, Germany emerged from technical recession in the second quarter, thanks to a carefully planned financial stimulus plan and package of policy reforms aimed at preventing a rise in unemployment. In 2014, as its continental neighbours struggled under crippling sovereign debt burdens, Germany recorded an €18bn budget surplus, equivalent to around 0.6 percent of GDP.

Until now, the country seemed fairly unshakeable. Its robustness has been reflected in Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose pragmatic and decisive leadership has allowed Germany to take its place in the world order without pomp or grandstanding. In recent months, however, a series of domestic and international cataclysms have converged to pose a grave threat to Germany’s superior economic standing.

If consumers are no longer willing to spend more on quality, the German auto industry will have to rethink its entire ethos

The country’s automotive sector is groaning under the weight of the US-China trade war, while the threat of a no-deal Brexit has paralysed national economic growth. Merkel’s decision to stand down as chancellor in 2021 spells further instability for Germany’s political system, which has become increasingly fragmented as a wave of populism has swept through Europe.

Taking a gamble

Germany is often referred to as the birthplace of the modern automobile; it was in the city of Mannheim that Karl Benz invented the first four-stroke combustion engine. In 1886, Benz produced and patented the world’s first motorised vehicle, retrofitting the engine he had created onto a three-wheeled stagecoach. This paved the way for the explosion of Germany’s automotive industry, which, by 1901, was producing 900 vehicles per year.

Flagship national manufacturers such as Audi and Mercedes-Benz were established in 1910 and 1926 respectively, while the first Volkswagen Beetle rolled off the production line in 1938. Despite its production coming to an end in June 2003, the Beetle continues to rank among the world’s longest-running and most-manufactured cars, with more than 21 million units being sold between 1945 and 2002.

Following this strong start, auto production stuttered in the mid-20th century due to the impact of the Second World War. The sector was revived in the 1950s, however, by the advent of the bubble car, of which BMW was a leading manufacturer. In the 1970s and 1980s, German car brands began to expand into overseas markets, but in doing so, faced significant competition from their Japanese and Korean counterparts.

“The way [German firms] responded was really quite interesting, as they did not look for cost savings primarily, but for increases in quality,” Dr Bob Hancké, an associate professor of political economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, told European CEO. “They took the gamble that the global middle class would grow and would be buying these higher-quality cars, which would be sold with a premium.”

Their bet paid off spectacularly. Not only did it cement Germany’s position as the fourth-largest auto producer worldwide, it also facilitated wage growth and upskilling among the industry’s 800,000 autoworkers. “You had this whole ecosystem around the German car manufacturers that was dragged up in quality terms as the industry moved up,” Hancké said.

Throughout the 21st century, the industry’s export focus shifted away from Europe and towards China and Latin America, which helped it to avoid the worst of the global recession, as those regions were not so badly affected by the 2008 crash. That year, for example, Germany’s vehicle output fell by just 2.7 percent, compared with 14.8 percent in France and 12 percent in Spain, both of which were far more reliant on the European market.

Moreover, the German Government was able to prevent mass job cuts in the auto industry with a carefully orchestrated package of financial stimuli. This included the ‘short-time’ work initiative, which saw companies reduce employee hours rather than making staff redundant. The government then supplemented any shortfall in worker income. “This was a very rational strategy, as the government package would roughly keep the wage of the worker at the level… it was [already at], while making sure that the wage cost for the employer [fell] sufficiently that it no longer would be a problem to keep on workers,” Hancké said.

Caught in the middle

In the past, Germany – and its auto industry in particular – has only had to grapple with headwinds from a single direction. In recent months, however, the country has been buffeted by international trade tensions while simultaneously being destabilised by a series of domestic blows. “Germany is highly exposed to trade, as exports account for 47 percent of its GDP,” Ana Andrade, an analyst in the Europe team at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), told European CEO. Of that total, approximately seven percent is exported to China, making it one of Germany’s largest export markets.

As part of its trade war with the US, China has raised import duties on cars, driving down demand and making it more expensive for German manufacturers to do business in the country. It’s not just the auto sector that has been hit hard by the tensions, either. The IHS Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index for German manufacturing stood at 45 in June 2019, signalling that the industry is in active recession. Industrial orders, meanwhile, were down by 8.6 percent in May compared with the previous year, the worst year-on-year drop since the financial crisis. Both of these sectors feed into a global supply chain that is highly reliant on China.

While the international landscape may appear grey at present, there’s a greater storm gathering on the domestic horizon. However, thanks to higher tax revenues and lower public spending in 2018, Germany is currently running a budget surplus of approximately €11.2bn, meaning there’s plenty of slack in the coffers to cope with a rough few months. What’s more, the German Government’s decision to reprise the short-time work initiative has helped keep the country’s unemployment rate at bay.

Learning from mistakes

What the country is not prepared for, however, is the impending shift away from fuel-powered vehicles that will redefine the future of the auto market. “Germany is particularly good at developing the next generation of cars on the basis of the technology [that it already has] – call it a form of incremental innovation,” Hancké said. “Moving towards electric vehicles is a big shift away from that development model [and towards] the type of innovation model that it is not particularly good at.”

While the international landscape may appear grey at present, there’s a greater storm gathering on Germany’s domestic horizon

Part of the issue stems from the country’s emotive attachment to the type of precise craftsmanship that is pivotal to the construction of a fuel-powered car. This is understandable considering Germany pioneered this sort of sophisticated and balanced engineering, but it also explains the historic reluctance on the part of car manufacturers to dedicate funds and factory space to the development of electric cars.

This attitude now appears to be changing, though, with the industry committing to invest nearly €60bn in electric cars and automation over the next three years. Some have raised concerns that this is too little, too late, as China has been pouring funding into electric vehicles for a number of years now and will likely capture a significant portion of the market if it can solve some of its own internal issues. However, Hancké believes there is a silver lining to Germany’s late entry: “[The industry] can benefit from the mistakes that all the others make, especially with regards to companies like Tesla. It’s not a problem for BMW or Mercedes to build a car like Tesla – the problem was that Tesla could build a car like Tesla, but not sell it, because they didn’t have a sales and service network.”

In modelling itself on companies like Tesla, however, Germany’s auto industry is placing significant confidence in the belief that the middle class will continue to pay more for quality – essentially doubling down on the bet it made in the 1980s. If this proves to be the case, Germany won’t be competing in the same high-output, low-cost leagues as China, meaning it will have eliminated that element of competition. But if attitudes have changed and consumers are no longer willing to spend more, the German auto industry will have to rethink its entire ethos – fast.

Falling apart

These industry-specific challenges may be compounded by the problems facing Germany’s wider business sphere – namely, the country’s weak physical and digital infrastructure. “There’s certainly an investment deficit that needs to be tackled in transport and education, but I think it’s especially critical for businesses in digital infrastructure,” Andrade said.

The country does not have a nationwide broadband network, and efforts to put one in place have “consistently foundered due to a mishmash of corporate greediness, government bureaucracy and that peculiar German fondness for having everything perfectly mapped out before they even get started”, according to Handelsblatt Today journalists Daniel Delhaes and Ina Karabasz. As reported by the pair, the government’s target to have the network up and running by 2025 is behind schedule – due, in large part, to the lack of incentives provided to the country’s telecoms companies. This in turn has caused conflicts with the powerful Federation of German Industries.

It seems bizarre that Europe’s leading economy doesn’t have nationwide internet coverage, particularly considering the country is running a budget surplus and could afford to up its public spending to achieve this. “It’s not that Germany doesn’t have the money to spend, but [rather] the political landscape currently doesn’t allow it to open the spending pot because there’s a very strong political and public consensus around maintaining a low level of debt,” Andrade said. “This, together with the volatile political landscape we’re living [in] at the moment, is preventing the government from undertaking significant reforms and investing where necessary.”

Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag, has become increasingly splintered in recent years, as the country’s proportional representation system has allowed for smaller, more extreme parties to gain seats. This has not only made it more difficult to pass policy, but has also challenged the authority of Chancellor Merkel, who has been in Germany’s top job since 2005.

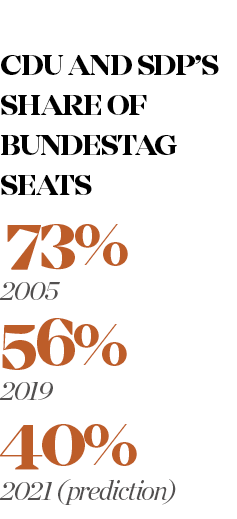

When Merkel was voted in, the ruling Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party, along with its coalition partners, the Social Democratic Party (SDP), held 73 percent of seats in the Bundestag. According to EIU data, this figure has since fallen to 56 percent, and opinion polls for the 2021 election predict it will decline further to just 40 percent. Andrade believes this represents a very high risk to political stability.

Merkel herself has already committed to stepping down in 2021, stating in her resignation speech last October: “The time has come to open a new chapter.” There has also been some speculation as to whether Merkel will step down before 2021, with commentators pointing to her bouts of shaking during a string of public events in July as evidence of ill health. In response, the German chancellor has said she is “very well” and emphasised that there is “no need to worry” about her health.

But even before these concerns arose, Merkel’s authority had been weakening for some time due to a variety of factors, including her decision to leave German borders open at the peak of the migrant crisis in 2015 – an action that drew backlash from within her own party and from the Alternative for Germany party, a far-right entity that has gained influence in recent months.

Bastion of stability

The intensifying speculation, both over Germany’s economic standing and Merkel’s unsteady physical and political footing, is symptomatic of a wider truth: a significant degree of Germany’s power lies in its symbolic stability.

Merkel’s leadership is a physical manifestation of that stability – she is reasoned and pragmatic, yet steely if her authority is challenged. To see her weakened has troubled not only her supporters, but also those at a global political level, whether they agree with her on policy or not. Put simply, she has long been recognised as a steadying force within both Germany and the EU.

Similarly, Germany’s economic prowess has meant that it has, on occasion, stepped up where other European countries have been unable to do so. In 2014, for example, it provided the largest share of funds to the European Financial Stability Facility, which was used to bail out Greece at the height of the sovereign debt crisis. And during the 2015 migrant crisis, it admitted thousands of refugees that were stranded in Hungary after Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán refused to offer asylum.

When Germany falters, Europe shudders – the continent knows that a fault in its engine spells trouble for the entire machine. These latest threats are no cause for smugness or gloating: they are a reminder that trials and tribulations can afflict even the most robust nations.