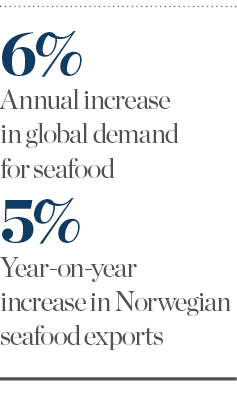

For the aquaculture industry, things have rarely been better. Globally, demand for seafood is rising to such an extent that the sector has been expanding by an average of nearly six percent annually, outpacing all other food segments. In Northern Europe, where the industry is particularly strong, exports have been rising rapidly to keep pace. The value of Norway’s seafood exports was up five percent year on year in 2018.

But what’s good for investors’ pockets is not always good for the planet. As seafood companies enjoy record gains, concerns are growing over the impact that they are having on the environment. Carbon emissions, antibiotic resistance and biodiversity loss are just a few of the most pressing issues. However, with the money rolling in, it can be difficult to apply the brakes.

Not so many fish in the sea

According to a recent report, aquaculture – seafood produced in fish farms – has now overtaken wild fishing as the world’s main source of seafood. Partly, this is the result of a growing global population, which has created more mouths to feed. It also reflects changing dietary habits: seafood is viewed as a healthier source of protein compared with meat, and demand has soared as a result. Aquaculture firms have been quick to respond, modernising their operations to meet customer needs.

“On the supply side, the industry has seen significant professionalisation and [the] adoption of technology, which has enabled producers to meet the growing demand,” a spokesperson for Benchmark, a leading provider of aquaculture solutions in genetics, health and specialist nutrition, told European CEO. “Specific areas of innovation [that] have contributed to this growth are the use of professional genetics programmes. Fish consumption is growing faster than all other major animal protein sources and with wild-catch production flat, the aquaculture industry faces a great opportunity.”

While fish farms were once thought of as a sustainable way of supplying the world with seafood, this is now being called into question

Another reason fish farms are thriving is due to the struggles that wild fishing is dealing with. Overfishing has depleted stocks the world over, often as a result of bycatches, where unwanted sea life is caught by accident. This has led to a renewed emphasis on aquaculture.

“Traditional fishing methods have proven insufficient to bridge the gap between supply and demand with, even in 2015, 90 percent of the world’s marine fisheries already overfished or fully fished,” explained Martin Fothergill, Board Director at Pure Salmon, a land-based Atlantic salmon-farming company. “And hence, since its commercialisation since the late 1980s, the key driver of the fish industry has been aquaculture. Nevertheless, there is still an enormous gap to fill.” The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation predicts that world food fish consumption will increase by 20 percent between 2016 and 2030.

While fish farms were once thought of as a sustainable way of supplying the world with seafood, this is now being called into question: as aquaculture expands, it too is causing sustainability issues for marine life.

Troubled waters

The aquaculture industry in particular needs to consider its environmental impact very carefully, as it is both a significant contributor to climate change and will be profoundly impacted by it.

“A recent report published by the [FAIRR] Initiative categorises aquaculture’s [environmental, social and corporate governance] challenges into 10 key areas: disease; antibiotic use; effluents; greenhouse gas emissions; habitat destruction and biodiversity loss; fish feed supply; transparency and food fraud; and forced labour,” Benchmark said. “These issues are not unique to aquaculture. They are present in other forms of large-scale protein production and can be overcome through a combination of technology, good husbandry practices, regulation and good governance.”

These issues will need to be tackled quickly, though, as problems have already started to emerge. Algal blooms, brought on by nutrient-rich effluents used in some fish farms, caused the loss of 10,000 tonnes of salmon in Norway earlier this year.

Aquaculture is also associated with heavy antibiotic use to prevent disease from depleting stocks. This, however, goes against broader efforts to tackle antibiotic resistance. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 33,000 people die each year in Europe due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“In addition to concerns over damage to the marine ecosystem, the use of antibiotics and hormones, and the presence of microplastics, certain aquaculture industries, such as salmon, have the added issue of transportation,” Fothergill explained. “Sea-based salmon farms (which provide around 80 percent of the world’s salmon supplies) are located mainly in Norway, Chile, Scotland and a handful of other countries, and therefore have to fly large quantities of fresh produce around the world. This, of course, conflicts with consumers’ increasing desire to reduce the food miles and carbon footprint [of] the products they consume.”

Crucially, there seems to be a lack of consumer awareness around the potential damage being done by commercial fish farms. Although in many cases farmed seafood has a lower carbon footprint than, say, beef, this is not always the case: for the same weight of protein, catfish farming actually produces more greenhouse gases than cattle farming, while shrimp, tilapia and carp are not far behind.

The net result

Fish farms will need to address sustainability issues eventually or risk damaging their own long-term interests, but a solution will need to be found that does as little damage as possible to their immediate growth prospects. Innovative players in the industry are pioneering new methods that may just be able to limit environmental damage while keeping profits high. At Pure Salmon, which has a proof-of-concept site operating in Poland, the solution lies in land-based farming.

“There is an increasing school of thought that believes the only way to truly solve these issues is to completely remove aquaculture from the sea and bring it onto the land,” Fothergill said. “This way there is certain to be no damage to the oceans by the farming process and equally no contamination of the farmed fish by parasites, disease and microplastics from the sea. Also, a fundamental advantage of this approach is that, once independent from marine environments, such aquaculture facilities can be located close to consumers to dramatically reduce food miles and eliminate air pollution.”

This approach used by Pure Salmon harnesses recirculating aquaculture systems to reduce the amount of water and space required in the farming process while creating healthy living conditions for the fish. It also means that produce is guaranteed to be free of pesticides, antibiotics, hormones and microplastics. Additional solutions, including more effective vaccine deployment and even some involving blockchain, are also being developed.

In addition, more extensive data collection and analysis is being implemented that would enable commercial farms to monitor their supply chains better and deliver a greater level of transparency. Keeping track of inputs and outputs allows farms to better determine the health of their fish stocks and identify where issues around sustainability are most prominent. Farms are also starting to act holistically, taking the wellbeing of fish, local fishing communities and marine habitats all into account.

Fortunately, there is now greater awareness of the environmental issues associated with aquaculture among producers, regulators and consumers. With the demand for seafood unlikely to abate, this is hugely positive. Meeting demand now is important, but so too is making sure this demand can still be met in the decades to come.