In 2011, disaster struck the Tennessee Valley as one of the worst tornado outbreaks ever recorded caused widespread power outages. The source of the power loss was not the destruction of generation plants, but rather the obliteration of the vast network that transports energy across the valley. More than 300 power transmission towers – supporting around 100 transmission lines – were destroyed by the storm.

After this catastrophe, it became obvious there was a need for a new power source that could replace this long-standing infrastructure and bring power production closer to the customer. It was my wife, Shirley, who helped me see what we needed to do.

In the aftermath of the April 2011 Super Outbreak, Shirley and I were sitting on our back deck. No one in the North Alabama area had power, but some of us were lucky enough to have generators to run a few appliances in our houses, such as freezers and water heaters.

By developing a turbine that is modular, you can increase or decrease the number of turbines being used to fit individual needs

While sitting there, Shirley noticed a large fan that we often use outside to keep cool during the hot summer months. It was just blowing in the breeze. She turned to me and asked a simple question: “Why can’t we power the house with that?” And the rest, they say, is history.

Starting from scratch

When designing our technology, we knew the main goal was to bring power to the people – literally, to bring energy closer to where people live. To do this, we had to rethink all of the work that had previously been done with traditional wind turbines. The technology was simply too large.

Humanity has been able to store energy captured from the wind since 1887, but it wasn’t until Albert Betz wrote a paper establishing the Betz limit – the theoretical maximum efficiency a wind turbine can achieve – that the design we know today was popularised. Since then, however, wind technology has not progressed much. Just imagine if Henry Ford had written a paper on how to build a car, and then all Ford Motor Company did over the next century was make it bigger.

That’s why, instead of looking at how turbines were already being built, we asked ourselves: how should we build a turbine? That fundamental question has allowed us to look at things differently. I quickly realised that a system of turbines should be used in place of one large one, much in the same way that solar panels are utilised. As such, we developed the MicroCube, which can be used to form larger systems known as WindWalls.

This is the clever bit: by creating WindWalls, we focus on surface area rather than ‘swept area’, which measures the circumference of the turbine’s blades. While this may seem like a small difference, it has a massive impact. To increase the swept area of a single turbine, for instance, you must make that turbine bigger, which increases the number of mechanical losses in the system.

In order to increase the surface area, however, you simply need to add more MicroCubes to the WindWall. As a result, you get an increase in power relative to the increase in surface area, incurring minimal losses. In many cases, you even see a net gain in performance.

Full speed ahead

There are many obstacles to be faced during the development process of a new technology, and not all of them are directly related to the tech itself. One of the larger complications I faced when forming the company was finding the right team to work with. When running a small business – especially a start-up – building a team that is talented across many different areas is challenging. It is very easy to find people with expertise in one field, but identifying staff who can take on projects outside their comfort zone is pivotal to success.

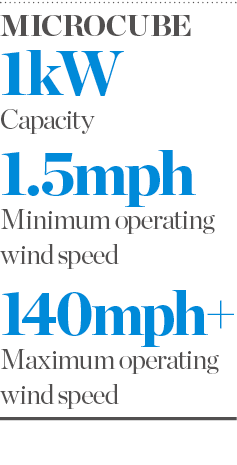

Fortunately, technology can help ease the development process, too. 3D printing, for example, has allowed us to move past many production hurdles. The ability to make an engineering change, send it off to be 3D printed and then test it in a production setting ensures time and money aren’t wasted on faulty solutions. Models and drawings are great, but they do not allow you to test ideas and make adjustments based upon real-world experiences. As a result of this rigorous testing, the MicroCube now has a capacity of 1kW and can produce power at wind speeds as low as 1.5mph and as high as 140mph.

This is an important distinction, because traditional turbines simply do not operate in certain wind speeds. When the conditions are perfect, typical turbines work very well, but speed restrictions limit where they can be built. Typically, this means large wind farms are located hundreds of miles away from the people who will actually use the energy they generate. In doing this, you decrease the security of your grid and actually lose around 30 percent of the power in transmission. But by developing a turbine that is modular instead, you can increase or decrease the number of turbines being used to fit individual needs.

This is the secret behind our technology: modularity and increased range of operation. Take a location that is susceptible to hurricane-force winds, for example: if the average wind speed is, say, 9mph, then traditional wind turbines won’t be able to function for the majority of the time, as the wind speed is below their operational threshold. What’s more, the gusting speed would be too high for the turbine to operate safely. A WindWall, meanwhile, would be able to function in both of these conditions.

Winds of change

Our invention is so much more than just a physical property. I would say the most unique aspect of our products is the approach we have taken to get to where we are today.

By using past experiences in aerospace, manufacturing, electrical and mechanical engineering, we found a way to take technologies that were widely used in other industries and combine them into a single product line that is truly one of a kind.

Our goal when branding American Wind was to have a company with a clear purpose: to bring power to the people. That is why we do what we do. Our company was founded out of disaster; our mission is to ensure the pain and anguish that we all felt during those weeks in April 2011 remains a thing of the past.