The world is in a period of unprecedented change. Nowhere is this more evident than in the healthcare and pharmaceuticals market: the population is ageing and living longer, new areas of unmet or underserved medical needs are emerging, and diseases are much more global in nature than they were previously.

A major disruptor to all of this – and a factor that is accelerating and magnifying these changes – is the degree to which the internet, social media and digital platforms are connecting healthcare professionals and patients. The sheer amount of information available to the public online has meant patients are much better informed about diseases and potential treatments. This has created both enormous opportunities and serious challenges for governments, regulators, pharmaceuticals companies and biotechnology firms alike.

Chain reaction

The fundamentals of the pharmaceuticals industry’s business model remain twofold: first, there is the need to drive research and development (R&D) in order to deliver a sustained flow of new, innovative medicine to the market. Second, it is important to manage the lifecycle of this medicine by improving access – this will help to maximise profitability and return on investment. Understandably, the focus of every pharmaceuticals company is R&D, as well as identifying ways to reduce the amount of time and money it takes to bring these important advances to market.

Even the biggest pharmaceuticals companies do not have the infrastructure or desire to operate in all 120-plus markets around the world

Arguably the biggest practical challenges facing the provision of effective healthcare are the management of access to medicine throughout its life cycle and the preservation of the global supply chain’s integrity to ensure prescribers and patients receive the right medicine at the right time. There are more than 120 pharmaceuticals markets in the world, and the development of technology – and the impact of digital connectivity – has meant that healthcare professionals and patients now have access to a huge amount of information about medicine. As such, they can interact online to discover what medicine is available, as well as learn how to get hold of it.

This has created two issues: first, there is now a much greater interest in, and demand for, earlier access to medicine under development around the world. Second, there is a greater risk of counterfeit and substandard medicine entering the supply chain, which is already creaking under the strain and struggling to cope with demand.

The risks are serious. According to the International Criminal Police Organisation, more than one million people die every year as a result of taking counterfeit medicine. What’s more, millions of units of medicine are seized and thousands of unregulated websites are shut down every year as governments try to contain the situation. Counterfeit and substandard medicine supply is escalating rapidly and has seen a number of high-profile global collaborations emerge in a bid to combat the problem.

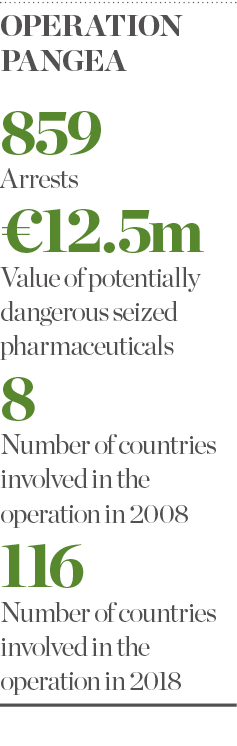

Operation Pangea, for example, was organised to target the advertisement, sale and supply of counterfeit medicine and medical devices that threaten public health around the world. It has evolved significantly over the past decade, increasing from eight countries at its launch in 2008 to 116 countries in 2018. With the initiative’s help, law enforcement, customs and health regulatory authorities are better targeting the illicit online sale of medicine and medical products, resulting in 859 arrests worldwide and the seizure of $14m (€12.5m) worth of potentially dangerous pharmaceuticals. In addition, around 3,700 websites, social media pages and online marketplaces have been shut down.

Supply management

So why is it so difficult to effectively manage access to specialist medicine? In simple terms, it develops from an imbalance in supply and demand, which could be due to several factors. First, demand for a medicine can be difficult to accurately forecast and therefore accurately manufacture in the required quantities. Second, the increasing complexity of new medicines and the manufacturing specifications require longer lead times, allowing for less flexibility when it comes to coping with demand on a global scale.

It is also challenging to predict real demand for a specific medicine when it is being requested from one part of the world – a low-price market, for example – to then be diverted to a higher-priced market elsewhere for increased profit. This is an unethical and unacceptable practice but, as the owner of the medicine, it is essential to manage the supply chain robustly enough to prevent this from happening.

Another major factor is that medicine is only launched or made commercially available in a relatively small number of pharmaceuticals markets – a maximum of 25 to 30 of the world’s 120-plus markets. And so the challenge becomes how to manage access for the 90 to 95 markets where the medicine is not licensed. This is what is meant by ‘unlicensed medicine’, but don’t be fooled by the term ‘unlicensed’.

Striking the right balance

Every country in the world has extensive regulations detailing how to manage access to an unlicensed medicine. As such, physicians can ethically access medicine that is not available in their country to treat patients in instances where all commercially available and licensed alternatives have been exhausted. Therefore, for those 90 to 95 markets where the medicine is not – and likely never will be – commercially available or licensed, it becomes a question of how to properly manage demand. This, in fact, has become an increasingly important part of a pharmaceuticals company’s medicine strategy: supply in these unlicensed markets can account for around 15 to 20 percent of a medicine’s global revenue and profit. So, if it is not managed efficiently, this can put further pressure on a company’s supply and demand forecast.

Even the biggest pharmaceuticals companies do not have the presence, infrastructure or desire to operate in all 120-plus pharmaceuticals markets around the world. Very few of those companies want to manage both the commercial/licensed market and the unlicensed market. As the developer and owner of a medicine, however, they must ensure the correct balance between facilitating ethical access to their medicine and creating a supply chain that manages that access compliantly and without risk.

Consequently, companies of all shapes and sizes need a partner or partners around the world that can work with them to achieve this balance. While there are many companies capable of managing the commercial/licensed element, there are very few that can handle both the licensed and unlicensed segments – this is due, in large part, to the complexity and bespoke nature of the unlicensed market. Clinigen can, however, handle both of these elements globally, and that’s why our corporate mission is to always deliver the right medicine, to the right person, at the right time.