Along Barcelona’s bustling Avinguda del Paral-lel sits Tickets, a restaurant in which individuals can be forgiven for thinking they are about to enjoy a circus performance rather than a Michelin-star meal. In Parlour in West London, Head Chef Jesse Dunford Wood emerges with a three-foot-long sword, while Berlin’s Nocti Vagus restaurant serves its diners in complete darkness. These are just a selection of the restaurants for which delicious food alone is not enough.

Some of these eateries have been described as ‘multisensory’, others ‘experiential’, but what they all have in common is their desire to play with the very concept of what a restaurant is meant to be. Often, unique sounds, smells and sights replace the formal setting of more traditional establishments. These other elements are just as important as the food and, what’s more, have a major impact on how we experience it.

More than a meal

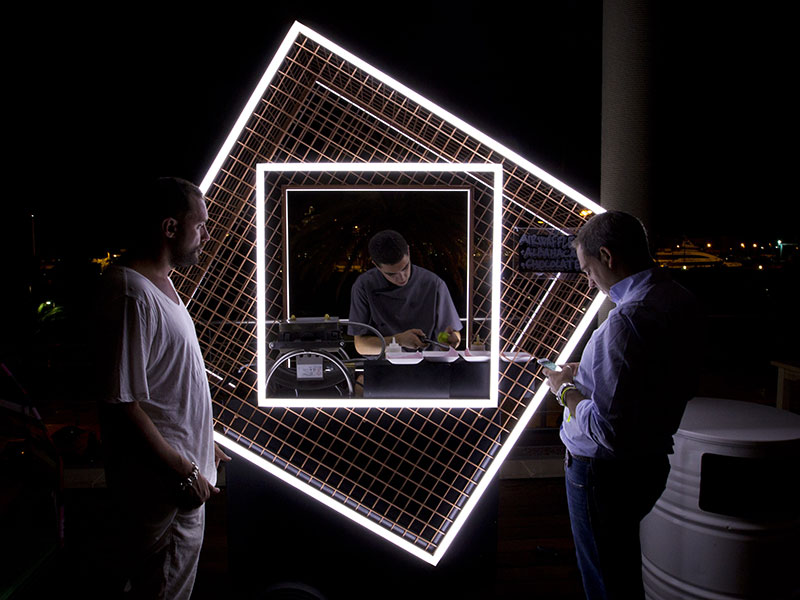

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of what constitutes a multisensory restaurant. In fact, many of them take vastly different approaches as a way of accentuating their distinctiveness. Having said that, there does seem to be one overarching constant: the off-the-plate experience is vying with the food to be the main draw. The spectacle – whether it comes from diners being suspended in mid-air or illuminated plates that animate your food – makes customers feel as though they are attending a must-see event rather than simply enjoying a meal.

At Wood’s Parlour restaurant, for example, stories are told to accompany the dishes, a mysterious pill is used to make sour foods taste sweet, and dramatic music is played through guests’ headphones to build the evening to a climax. The dishes themselves are important, but they are only a part of the dining experience.

The spectacle makes diners feel as though they are attending a must-see event

rather than simply enjoying a meal

“I don’t really take the food more seriously than the performance,” Wood explained. “It’s all part of the package. I am a chef that has trained for 20 years in fine dining and I’ve been brainwashed into thinking fancy food is the most important thing, but now I value the rounded experience much more. Food is an important aspect, but it’s not the be all and end all.”

Chefs at multisensory restaurants understand that the appreciation of food goes far beyond our taste buds – anyone who has ever wondered why fish and chips taste better with a sea breeze blowing through their hair or developed a craving for turkey upon hearing Christmas carols can attest to that.

Food for thought

While some have dismissed the rise of experiential restaurants as little more than a gimmick, the chefs involved – and their satisfied customers – certainly feel the use of unique sights and sounds is a worthwhile addition. What’s more, the theatre created at these establishments is, in a sense, simply a heightened version of how we experience all of our meals, which are by their very nature multisensory.

Charles Spence, Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford and author of Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating, has written extensively on the subject of taste and food experience. Spence argues that taste is “a construction of the mind more than the mouth”. Hence, our appreciation of food is always affected by our surroundings.

Research has shown high levels of background noise can heighten our ability to perceive savoury flavours, rounder desserts are perceived to be sweeter and heavier cutlery can simply make food taste better. No one is suggesting that different lighting or music can make a bad dish taste good, but it can subtly influence our perception of flavour.

“I think that we all assume that taste comes from our tongues, and from the food and drink we feel moving around in our mouths,” Spence said. “However, that is an illusion. In fact, all of your senses are involved. Everything from the colour of the plate to the weight of the cutlery in your hands, from the background music to any ambient scent, as well as the lighting and even the softness of the chair you are sitting on – it all has some effect on what we think about the food and drink we are tasting.”

Multisensory restaurants are simply looking to influence our experience of food in a more overt way. “What we taste is always a function of where we taste, and what we have been told about the food we eat,” Spence continued. So, whether diners are listening to Johann Strauss while eating flaming marshmallows or struggling through an in-flight meal at 30,000 feet, science has shown all of our senses have a huge effect on our appreciation of flavour.

The gravy train

Multisensory restaurants can certainly provide customers with a unique experience, but this isn’t the only reason why more and more chefs are taking an experiential approach to fine dining. As always, money also plays a part, and there is a growing body of research that suggests customers at these establishments are more willing to part with their cash.

One of the world’s most expensive restaurants, Sublimotion in Ibiza, delivers a 20-course ‘gastro-sensory’ meal that costs €1,500 per person. Of course, the food has to be of an extremely high standard, but guests are also paying for the privilege of seeing an edible version of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss painted on the table. When questioned about the price tag in the past, Head Chef Paco Roncero has responded by calling his restaurant the “cheapest life-changing experience anyone can have”.

Spence notes that a multisensory restaurant needn’t be particularly expensive, but it can certainly give restaurants a “better chance of sticking in people’s minds”, which can therefore help with repeat custom. In fact, recent studies indicate that 75 percent of people believe unique dining experiences are worth paying more for. Similarly, 50 percent of people would pay more for the exact same menu if it included chef interaction – a common feature at multisensory restaurants.

Even if a restaurant is not pushing an explicitly multisensory angle, it can still use more than just its food to influence how much customers spend. A study conducted in 1986 by R E Milliman, a US-based professor of marketing, found playing slower background music caused diners to spend longer eating, increasing the money they spent on drinks and boosting restaurant revenue by 15 percent.

Even if these avant-garde restaurants profess money isn’t their primary motivation, the more outlandish elements they introduce, the more they will find themselves open to accusations of elitism. After all, it’s hard to see what restaurants using virtual reality headsets or exhilarating light shows have in common with most people’s day-to-day experience of food.

However, there is no reason why innovative approaches being explored at high-end eateries cannot be put to use in more conventional meal settings. If rounder food makes people think there’s more sugar in a particular dish than there actually is, then this could present a novel way of tackling obesity. Likewise, the use of particular aromas could reduce salt consumption. Even something as simple as using smaller plates can promote healthier eating.

Our enjoyment of food is always multisensory, but particular restaurants are taking this to another level. Even if premium culinary institutions may seem a million miles away from tucking into a sandwich at work, eating remains one of the few truly universal human experiences, and this includes any accompanying sights, smells and sounds.