Since the 1980s, performance related pay packages tying executive compensation to the financial success of the companies they command has produced thousands of millionaires and even a few billionaires. Although John Mariotti, founder of The Enterprise Group, notes that the most outstanding performers are generally more motivated by the challenge than huge financial awards, the long-running bull market of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century meant that nearly everyone did well.

But massive wealth brings its own problems, which few are prepared for. In this first of a three part feature, European CEO will consider the drives, motivations and challenges of a four of the world’s top billionaires.

Sources of wealth

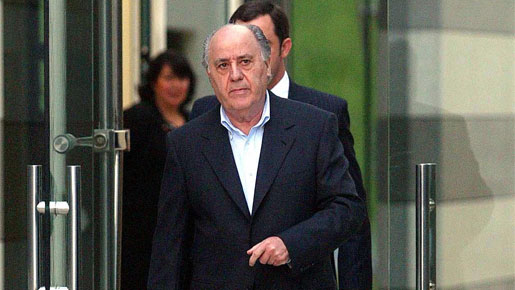

It used to take several generations to amass the kind of fortune that will support at least one domestic economy. Today, inflation, globalisation, political upheaval, technology and rapid shifts in consumer taste have made it possible for a canny individual to become a billionaire in a lifetime. Amancio Ortega did it. Ranked ninth in the Forbes 2010 Billionaires list, Ortega was born in Spain in 1936. His father worked on the railroad and his mother augmented the family income by working as a maid. Amancio Ortega started work at the age of 13 as a delivery boy for a local shirt maker.

He never attended higher education, but made his own study of the textile industry in which he settled for the rest of his working life. He noticed how the cost of products increased as they travelled from the manufacturer to the consumer. He also noticed that only wealthy customers could afford to purchase fashionable designer clothing in the shops. These two observations would form the basis for the fashion empire that eventually made him a billionaire.

At the age of 27 Ortega established his first company, producing bathrobes. His primary focus as he built his business was on creating high quality fashion at affordable prices, and he had a huge market waiting in the large section of the Spanish population that had never had access to designer wear. In 1975 he opened his first retail store called Zara, which was an almost overnight success. By 1985 he created holding company, Inditex, to manage Zara’s expanding network of over 75 stores across Spain, along with a growing number of smaller chains that had been added to his fashion empire. The Inditex Group was floated in 2001, making Ortega one of the wealthiest men in the world overnight.

Another self-made billionaire achieved his fortune in even less time. Roman Abramovich, one of Russia’s notorious post-communist era oligarchs, was born in 1966. Orphaned at the age of two, he was brought up by an uncle in an inhospitable but oil-rich region of northern Russia. He showed himself to be both hard-working and opportunistic from an early age, with reports of him selling black market gasoline to commissioned officers during his two year stint in national service.

Back in civilian life, he carried on his black market trading in street markets, set up a couple of small manufacturing companies and briefly worked as a commodities trader. When President Gorbachov relaxed controls on private industry in the late 1980’s the young Abramovich was already well placed to multiply his growing wealth with businesses ranging from making dolls to farming pigs and trading oil. Then in 1992, President Yeltsin attempted to create his ‘stakeholder society’ in which the majority share in the country’s previously state-owned resource and utility companies would be owned by individual workers, with the state retaining a 30 percent holding. Citizens were issued with vouchers worth approximately one month’s wages to trade in for their shares.

Unfortunately, a concurrent decision to deregulate pricing in Russia led to a collapse in the rouble on international currency markets, wiping out the value of peoples’ savings almost overnight. Workers needed cash to feed their families, not shares in companies, and Roman Abramovich among several others set up market stalls to purchase vouchers from hungry citizens at a fraction of their original face value.

By this time, Abramovich had developed a close working relationship with Boris Berezovsky, a Russian tycoon who facilitated his entry in to the inner circle at the Kremlin. When Yeltsin turned to his friends for financial support to help him win the next election, Abramovich was in a position to oblige, alongside Berezovsky and several others. The deal, in which wealthy individuals extended loans that were secured against the government’s remaining holdings in the country’s resource, transport and utilities businesses, created vast wealth for the oligarchs, many of whom are being pursued by the current administration for the return of Russia’s economic crown jewels.

Not all the billionaires in the Forbes list have made their own fortunes – some have inherited wealth from earlier generations within their families. Take Susanne Klatten, for example. The richest woman in Germany, she is the last of six children born to Herbert Quandt from his three marriages. Her grandfather, Gunther Quandt, had been a savvy businessman with alleged Nazi connections. Herbert joined his father’s business empire in 1940 and was an active director of the group’s development through the Second World War and beyond. By the time Gunther Quandt died in 1954, the conglomerate had holdings in over 100 businesses, including battery manufacture, metal fabrication, textiles and chemicals, plus a 10 percent holding in Daimler Benz and 30 percent of BMW.

The group was split between Gunther Quandt’s two sons, and Herbert, who took the ailing BMW, is credited with saving it from bankruptcy, making a huge fortune in the process. The pragmatism and discipline which he brought to the management of his business empire was also deployed in raising his youngest child. Susanne was brought up to live a restrained, if privileged lifestyle. Having attended ‘normal’ schools and earned a university degree in management, she did a traineeship at BMW where she met her future husband.

The Quandt family history of employing forced labour to supply the Nazi war efforts with uniforms and batteries made Herbert particularly sensitive to the need to shield his children from possible kidnap or exploitation. Susanne, the target of a foiled kidnap attempt when she was 16, was taught to be wary of the motivations of everyone she met. It is said that she used an alias for much of her young adult life, only revealing her true identity to her future husband after they had been dating for several months. When Herbert Quandt died in 1982, she inherited 12.5 percent of the shares in BMW and his controlling interest in Altana AG, a chemicals company. Her fortune is currently estimated at $11.1 billion.

Lilianne Bettencourt is another heiress with reason to be wary. Ranked seventeenth in the Forbes list, she is the only daughter of Eugène Schueller, a chemist who started life selling his patented hair dyes to Parisian hairdressers. By the time Lilianne was born in 1922, his company, L’Oréal was already selling hairdyes as far afield as Italy, Austria, The Netherlands, the UK, US, Canada and Brazil.

Despite the family’s growing fortune, however, life was not straightforward for the young Lilianne. Her mother passed away when she was just five, leaving her to be brought up by her father. Eugène Schueller, meanwhile, is said to have developed close ties with the Nazi regime in France, hosting meetings of La Cagoule, a fascist group with Nazi sympathies, at L’Oréal headquarters. This may be one reason for the family’s aversion to publicity. Very little is known about Lilianne’s life until her marriage in 1950 to a French politician called André Bettencourt. In 1957, Eugène Schueller died, leaving his fortune and his business to Lilianne.

Life of the rich and famous

“[Money] cannot buy you happiness,” Roman Abramovich once told Dominic Midgeley of Management Today. “Some independence, yes.”

But it is not the same kind of independence enjoyed by people living outside the rarefied atmosphere of the mega-rich. On the positive side, they have the financial means to indulge in any hobby, sport or other venture that takes their fancy – but money doesn’t » make them good at it, and the public is fascinated by their failures. A perfect example is Abramovich’s own recent whim to climb Mt Kilimanjaro in Kenya. Rising 19,330 feet out of the Serengeti desert, Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain that can be walked up without the need for specialist climbing and survival gear. Don’t be fooled, however: up to 20 people per year die in their attempt to reach the top.

In September 2009, Abramovich flew six friends in on his own Boeing 767 jet, hired more than 100 porters to carry all their gear and began to walk up the most difficult western slope, having apparently undertaken little or no physical training to prepare for the rigours of altitude. After 15,000 feet he collapsed with breathing difficulties and had to be carried back down the mountain.

Back in the office, Abramovich continues to take an active role in his shifting business empire, his ownership of England’s Premier League Chelsea Football Club, and, until two years ago, his governorship of the remote Siberian region of Chukotka. He does not exactly shun publicity, but does not like details or criticism of his ventures to be aired.

The size of his fortune makes public interest inevitable, however, and speculation abounds over the possible criminal nature of some of his business dealings, and the motivation behind his extraordinary philanthropy towards the people of Chukotka (he is estimated to have poured over €500m of his own money into building schools and hospitals, raising living standards and improving community life for the regions’ 50,000 inhabitants).

Philanthropy has been at the heart of Liliane Bettencourt’s work throughout her lifetime. Following their marriage, her husband André Bettencourt joined L’Oréal’s executive team, rising to become deputy chairman and one of the richest men in France. Liliane was a well-known socialite who used her inherited wealth to found the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation in 1987. The Foundation supports humanitarian and social programs, particularly those related to care for HIV/AIDS patients in Africa, the protection and education of children, and support of social housing and job training projects. The foundation awards the “Liliane Bettencourt Prize for Life Sciences” annually to European researchers under 45.

Now well into her 80s and recently widowed, Bettencourt retains her 27 percent holding of L’Oréal shares and sits on the board where she makes sure the company holds the values that her father instilled.

Susanne Klatten continued to pursue her business career even after she inherited 12.5 percent of BMW’s stock and controlling interest in the chemical company, Altana. She worked with ad agency Young & Rubicam, Dresdner Bank, McKinseys and the Reuschel & Company Bank before being appointed to the supervisory board of BMW in 1997. She now owns over 80 percent of Altana, which she helped build and float on the German stock market, and she sits on the boards of both Altana and BMW. She is also a committed philanthropist, and has been awarded the Bavarian Order of Merit.

Both Klatten and Bettencourt share an aversion to being in the public eye with Amancio Ortega. Despite his billions, the Spanish fashion retail billionaire has a reputation as a private and down-to-earth person who never gives interviews and shuns the extravagance of the wealthy. Although he has contributed significantly to the local economy by refusing to move jobs to lower cost regions, few Spaniards would recognise him on the street. It has been reported that on the day of the public flotation of Inditex, Ortega turned up to work in his trademark jeans as usual, watched the news on television to find out that he had just earned $6bn, and then ate lunch in the company canteen. Now 73, he lives quietly in A Coruña with his second wife.

Sadly, neither Bettencourt nor Klatten have been as successful as Ortega at avoiding unwanted publicity. Both heiresses, despite or perhaps because they were brought up with the knowledge that they would inherit such vast wealth, managed to make successful long-term marriages and bring up children (Bettencourt has one daughter, Françoise Bettencourt Myers, and Klatten has three offspring). Yet both have suffered the humiliation in later life of seeing their names splashed across the national press, linked to allegations of fortune-hunting and worse.

The BMW heiress turned out to be the whistle-blower in her own unfortunate affair. Naturally reclusive, she uncharacteristically befriended an attractive fellow guest at the Austrian spa she attended for a stress release break. He turned out to be charming company and the two were soon walking out in the surrounding hills, talking and drinking tea. But dig a little deeper and it turns out that Klatten’s companion, Helg Sgarbi, was an accomplished gigolo, who had allegedly seduced at least three other wealthy German women. Dig even further and you encounter allegations of cult membership with an Italian named » Barretta, and even Mafia connections.

What is certain is that Sgarbi initially charmed €7m from Klatten to ‘help him out of a difficult and potentially life-threatening run-in with the American Mafia’. As she began to cool to the relationship he resorted to blackmail, threatening to show incriminating video footage of the two engaged in sexual relations (filmed by Barretta from an adjoining hotel room) to her husband and the press. It was at this point that Klatten, showing her steely negotiating skills and great courage, confessed to her family and the police, even helping to set up the sting that resulted in Sgarbi’s arrest in late 2008. The press was then filled with stories about Sgarbi’s previous conquests and extortion attempts, the cult relationship with Barretta and a disturbing suggestion that Sgarbi was actually looking to avenge his Polish Jewish father’s suffering as a slave labourer in a BMW factory during the Nazi regime.

In many ways Lilianne Bettencourt’s story is the more tragic, in that there is no question of a sexual dalliance and the complainant is none other than her own daughter. The alleged fortune hunter in the case is a man named François-Marie Banier, a homosexual writer and photographer who has befriended many famous and well-heeled people throughout his career. In the mid-1980s he was introduced to the Bettencourts and the three became firm friends; some acquaintances described him as the son the couple never had. Over the years, Banier received cash, paintings and life insurance policies from the Bettencourts, and L’Oréal sponsored several exhibitions of his work.

Within months of her father’s death in 2007, Françoise Bettencourt Myers filed a complaint against Banier for ‘abus de faibless’, the exploitation of physical or psychological weakness for personal gain, claiming that he was preying on Lilianne Bettencourt because of her age. Estimates of the value of all the gifts that had been handed over were in the region of €1bn. When the courts refused to investigate without a complaint from the alleged victim or an independent assessment of her mental condition, Myers, who also has a seat on the L’Oréal board, applied to have her 87 year old mother made a ward of the court.

In a statement, Liliane suggested that far from being mentally feeble, she was in full control of her faculties and had “decided to split up my fortune while I am still alive”, yet another luxury that some billionaires may not get to enjoy, if their children have anything to say about it.