“What’s interesting about photography”, says Icelandic artist Einar Falur Ingolfsson, “is that it is something that everybody owns and every- body does”. Where painting, sculpture and performance art are the domain of the professional artist and therefore remote, alien and with a reputation for being difficult to understand, photography is familiar and everyday, an art form that is fundamentally accessible.

Ingólfsson, one of Iceland’s best known artists, is talking to me on the eve of the opening of Frontiers of Another Nature: Con- temporary Photographic Art from Iceland, a group exhibition at the Frankfurter Kunstverein that will include 10 photographs from his Saga-Places series. The series sees the art- ist walk in the footsteps of William Gershom Collingwood, an English artist and historian who toured sites associated with the Icelandic Sagas in the 19th century and published an illustrated account of his journey.

The show brings Ingólfsson’s work together with that of eight other Icelandic photographers, to explore innovative approaches to landscape and the complex relationship between man and his environment. Presented in collaboration with the Frankfurt Book Fair, which each year runs exhibitions and events around a different country theme, Frontiers of Another Nature is intended to work as a platform for contemporary artists unknown out- side Iceland. Given the directness of photography as a medium, of course, it will also offer visitors to the show a glimpse into the realities of life on this sparsely-populated island.

This is something that Celina Lunsford, artistic director of the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt and one of the show’s curators, is aware of. Frontiers of Another Nature, she says, is not intended as “a travelogue about a country”, but as something more subtle than that: a route into Icelandic photographic practice, itself a very varied field.

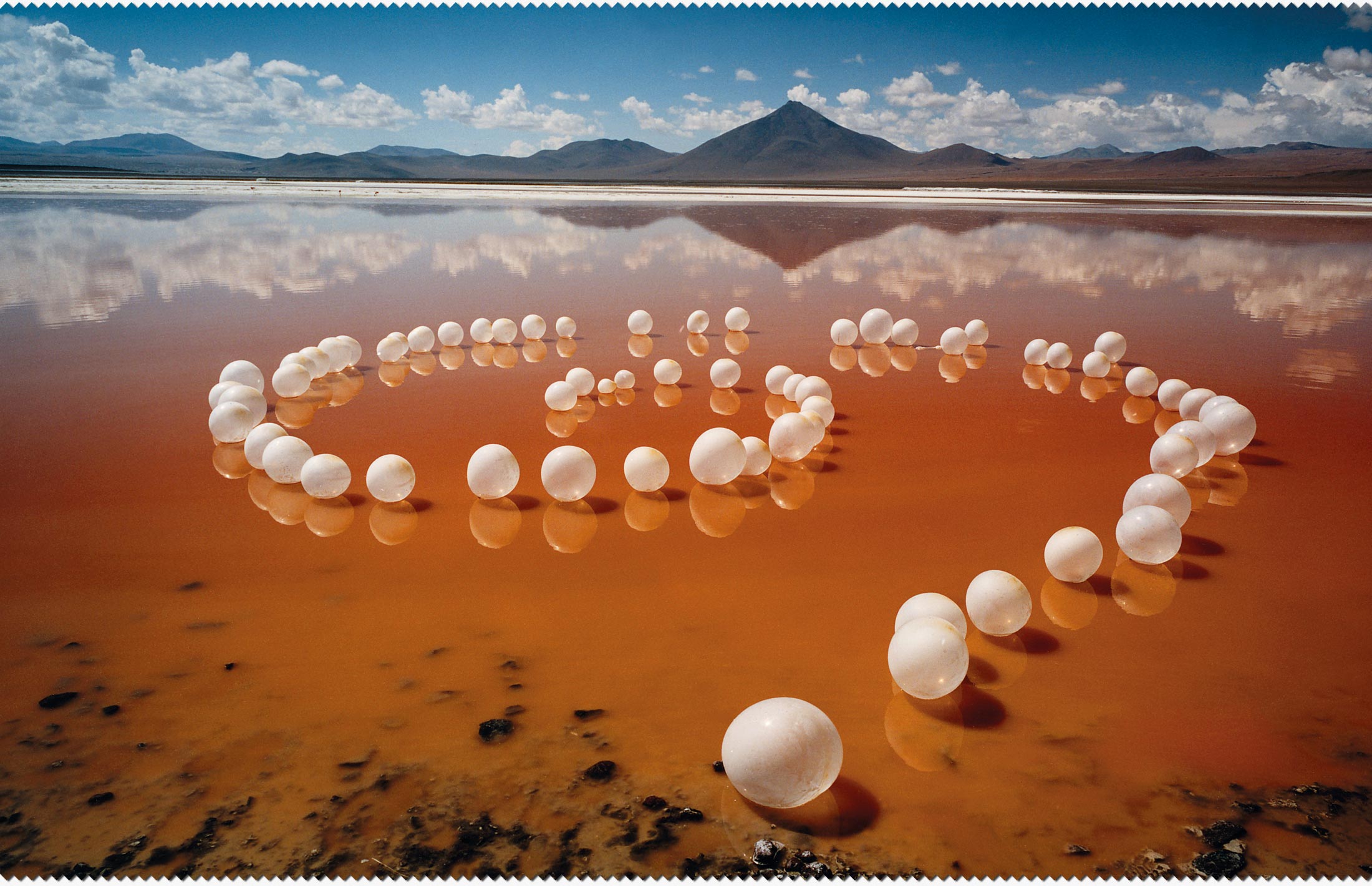

Aside from Ingólfsson, Lunsford says, the only artists featured in the show already known within Germany are the multimedia artist Haraldur Jónsson, showing TSOYL (The story of your life), a large series of poetic photographs exploring the minutiae of suburban existence; and the performance art trio Icelandic Love Corporation, showing a project called Mother Earth, a series of images of a long-term outdoor installation piece about the impact of a power station. More traditional landscape photography will be represented by Pétur Thomsen’s series Imported Land- scape, which documents the construction of a massive hydroelectric power plant on what was formerly the largest area of unspoilt wilderness in Europe. Visitors will also be introduced to Ingvar Högni Ragnarsson, who photographed the wall of a Reykjavik construction site each day for over a year for a project that explores the changing nature of the urban environment.

Lunsford is thrilled to be able to stage such a diverse mix of work in one exhibition. She believes that coming at the project as “an outsider” to Icelandic art has been crucial in letting her draw thematic links between series that might never meet in an Icelandic context. The example she gives is of Icelandic Love Corporation exhibiting side-by-side with Pétur Thomsen, a combination that shows “two very different ways of working”.

These artists’ varying technical or stylistic approaches aside, they are all, in Ingólfsson’s words, “at the forefront of finding new ways to show the people of Iceland how nature looks, what’s out there.” Lunsford points to the environmental impact of Iceland