The enduring success of the Rolling Stones marks a number of lessons that many corporations could learn. Celebrating their 50th anniversary this year, a group of London rockers have been at the forefront of developing the music industry as a money making machine.

“When you look at what a stadium show was pre-Steel Wheels, it was a bit of a scrim, and a big, wide, flat piece of lumber, and that was it. The band turned a stadium into a theatre.”

Many artists have attempted to copy the template set by the Stones, but few are likely to ever see the sort of adulation, let alone revenues, that the band has received. As they start to raise their creaking bones up for a series of concerts and re-releases likely to swell their already considerable bank balances, we look at how the band changed the music industry from its small and chaotic roots to a global sector worth as much as $170bn.

Starting up

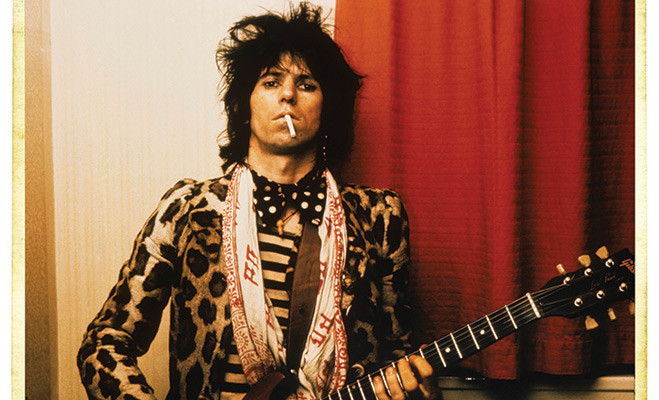

Formed in 1962 by childhood friends Mick Jagger and Keith Richards after a chance meeting at a south London train platform, the Rolling Stones have gone on to record 22 studio albums, tour extensively across the world, and rake in billions of pounds. Their albums have not only received critical acclaim, but have gone gold 42 times and platinum 28, selling a total of 200 million worldwide. From the beginning, the band had a better understanding of their audience and their brand than many other brands. Spearheaded by lead singer Mick Jagger, who had briefly studied business at the London School of Economics, the Stones positioned themselves as the grittier alternative to the wholesome Beatles, who were dominating the music industry at the time. They offered a reflection to the risk and rebellious new generation that was emerging in 1960s London.

The music industry during that period was not at all profitable, and certainly not for the artists. Jagger told Fortune in an interview in 2002: “When we started out, there wasn’t really any money in rock and roll. There wasn’t a touring industry; it didn’t even exist. Obviously there was somebody maybe who made money, but it certainly wasn’t the act. Basically, even if you were very successful, you got paid nothing.”

Although he had received some form of business training, Jagger says he was too inexperienced in the early days, which led to him being taken advantage of: “I’ll never forget the deals I did in the ‘60s, which were just terrible. You say, ‘Oh, I’m a creative person, I won’t worry about this.’ But that just doesn’t work. Because everyone would just steal every penny you’ve got.” T he Beatles bucked the trend during those early years, says Jagger, because of their record sales. He told Fortune: “In the early days you got paid absolutely nothing. The only people who earned money were the Beatles because they sold so many records.”

Jagger said that despite his business training, he wasn’t initially cut out for managing the bands affairs: “I don’t really count myself as a very sophisticated businessperson. I’m a creative artist. All I know from business I’ve picked up along the way. I never really studied business in school. I kind of wish I had, kind of, but how boring is that?”

Prince Rupert to the rescue

It was not until the beginning of the 1970s, when the Stones split from their first manager Allen Klein, that their financial success took off. Hiring an aristocratic merchant banker called Prince Rupert zu Loewenstein to sort out their financial affairs, the band were now in a position to avoid being ripped off by record labels and concert promoters.

Loewenstein’s influence over the band was considerable. Richards said of him: “He is a great financial mind for the market. He plays it like I play guitar.” Richards further emphasised his trust of Loewenstein’s judgement when he said: “As long as there’s a smile on Rupert’s face, I’m cool.” Loewenstein would restructure the band as a a blue-chip company with each band member as a partner, and then incorporating a series of subsidiary companies that would handlee the different aspects of the group’s activities. Jagger says of the structure: “They all have their different income streams like any other company. They have different business models; they have different delegated people that look after them. And they have to interlock.”

The Stones as a brand

Jagger would go on to gain a reputation for making astute decisions in guiding his band’s career. Eurythmics song-writer and music producer Dave Stewart described Jagger’s impact on the music business to Worth magazine: “People tend not to see music as a business, but once you work with a musician like Mick Jagger, you immediately see how aware he is of his brand – both the Mick Jagger brand and the Rolling Stones brand.”

It was this branding that is another recognisable facet of Jagger’s skill. In 1969, he approached London’s Royal College of Art with the aim of commissioning images for the band. Meeting the artist John Pasche inspired one particular logo. Pasche said that: “Face to face with him [Jagger], the first thing you were aware of was the size of his lips and mouth.” It was his ‘Tongue and Lip’ design that would initially adorn the ‘Sticky Fingers’ album, but would subsequently be used on all Stones-branded material, and become the most recognisable musical logo in history.

With their musical heyday considered to have climaxed in the early 1980s, the band managed to maintain their popularity through a series of globetrotting tours that would redefine the concept of live performances and create a wildly profitable industry. In 1989, Loewenstein would bring concert promoter Michael Cohl into the band’s tour group. Cohl’s job was to turn the operation into something bigger, more efficient, and profitable. On the ‘Steel Wheels’ tour, he achieved that.

Cohl told Fortune: “First and foremost, the show itself was the seminal, watershed point. When you look at what a stadium show was pre-Steel Wheels, it was a bit of a scrim, and a big, wide, flat piece of lumber, and that was it. The band turned a stadium into a theatre. It all started with Mick. He simply said, ‘We have to fill the end space.’ It was complicated to the third power and expensive to the fifth. But it worked.” Another area that the Stones have seen great revenue streams is through the licensing of their music. In the mid-90s, Microsoft paid the Stones $4m to use their track ‘Start Me Up’ in one of their adverts, and other songs have since been used by countless corporations wanting to associate themselves with the band’s image. Income from publishing has given the band their greatest revenues, says Jagger: “Music publishing is more profitable to the artist than recording. Its just tradition. There’s no rhyme or reason. The people who wrote songs were probably better businesspeople than the people who sang them were.

Publishing: the next step

“You go back to George Gershwin and his contemporaries – they probably negotiated better deals, and they became the norm of the business. So if you wrote a song, you got half of it, and the other half went to your publisher. That’s the model for writing.” The band have licensed their songs over 200 times to films, according to the Internet Movie Database (IMDB), second only to Elvis. Richards told Fortune when asked what was his greatest source of income: “Performing rights. Every time it’s played on the radio. I go to sleep and make money – let’s put it that way.”

The band has stayed in the limelight, despite taking some years off from touring and recording. Since completing their mammoth ‘A Bigger Bang’ tour in 2007, which raised $558m and saw an average audience of 32,500 people, the band has seen a Martin Scorsese-directed documentary made about them, as well as countless stories about their personal lives keeping them on the front pages of the tabloids. They have continued their bad behaviour well into their twilight years, playing up to every ageing fan’s fantasy. Richard caused a stir when drunkenly falling out of a tree while on holiday, while bassist Ronnie Wood left his wife of 24 years for a 20-year-old Russian waitress.

They have been set to emerge in the coming months from their recent slumber, with a series of concerts that may or may not culminate in a much-rumoured performance at the Glastonbury Festival in the UK in June 2013. Before then, the band will release yet another career-spanning greatest hits collection, titled ‘GRRR!’. Although fans may have long given up hope of the band releasing anything as good as their older material, the new album and the concerts will inevitably sell out, proving their business prowess, and providing the band and their management even greater wealth. As a business, The Rolling Stones are definitely well ahead of the curve.