Freedom of speech is a cornerstone of modern democracy, and journalism in particular acts as a means of conveying challenging views to the wider public. Sometimes, in order to tackle subjects deemed off-limits, satire is employed as a way of challenging the powerful. Indeed, satire has gone hand-in-hand with journalism over the last few centuries as a way of holding the rich, the powerful, and the corrupt to account.

The press has carried satirical cartoons as a light-hearted way of raising serious points, frequently skewering serious figures with a joke. Nowadays, almost every newspaper in the world carries a cartoon featuring a prominent story of the day. Sometimes, these can be hugely controversial, occasionally in a way that oversteps the mark, but often they tell the truth in a manner that a typical piece of editorial would struggle to.

Perhaps the first example of a classic satirical cartoonist is English painter William Hogarth, whose work in the early 18th century frequently lampooned British politics and political figures. The field developed around the end of that century, with British and French artists taking turns to mock each other and their own leaders as a means of highlighting the major issues of the day. By the 19th century, satirical magazines started to spring up, solely catering for such work.

Modern examples include acclaimed British cartoonist Gerald Scarfe, perhaps most famous for his work with rock band Pink Floyd on their album The Wall. His work, however, has mostly been found in publications such as The Sunday Times and The New Yorker, where he has mocked and derided political figures throughout the world to devastating effect.

Even popular US television cartoons like South Park and The Simpsons frequently satirise popular news and culture. The country has also led the way in recent years, with nightly satirical news shows like The Daily Show, hosted expertly by Jon Stewart for 17 years. His departure later this year will cause a huge sigh of relief from politicians and the media alike – there can be no finer praise for a satirist.

Such has been the effectiveness of satire, politicians have been felled, monarchs ousted, and the credibility of the ruling classes shattered. Satire has kept the public informed – and amused – amid the many serious voices in the news. In recognition of this heritage, European CEO looks at some of the most influential magazines that have mocked and caricatured history’s most powerful figures.

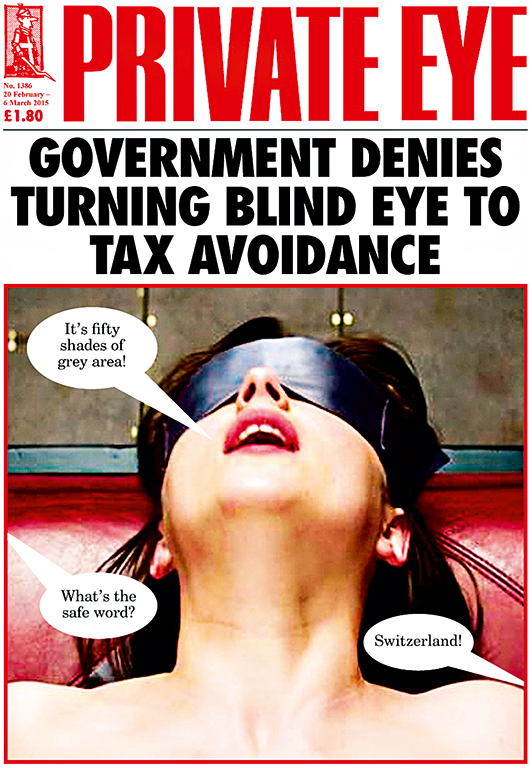

Private Eye

The UK’s foremost satirical magazine, Private Eye has been mocking the great and the good of the British establishment since its launch in 1961. Founded initially by Peter Usborne, Andrew Osmon, Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton and Christopher Booker – a group of school and university friends – the magazine came to prominence at a time when satire itself was really taking off in the UK. Funding came from hugely popular comic Peter Cook, who would go on to act as the magazine’s benefactor and occasional contributor until his death in 1995. Other notable contributors have included Auberon Waugh, Gerald Scarfe, Craig Brown and Claud Cockburn.

While it is widely known for its humorous cartoons and lampooning of politicians, the magazine is also one of the most fearless sources of investigative journalism in the country. It has become famed for publishing stories more mainstream publications would deem too risky, with journalists at many of those publications choosing to write anonymously for Private Eye on the side.

Paul Foot, whose campaigns uncovered many scandals throughout British society, initially led the magazine’s charge in investigative journalism. He oversaw such revelations as the Profumo scandal that engulfed Harold Macmillan’s government in 1963, and the resignation of Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in 1972 over links to corrupt property developer John Poulson. Foot’s death in 2004 led to the magazine launching its Paul Foot Award for investigative journalism. More recently, the magazine led the campaign against superinjunctions that allow prominent figures to silence the media with pre-emptive legal action.

Private Eye has also made a habit of mocking the rich, famous and powerful. Billionaire tycoon Sir James Goldsmith was dubbed ‘Sir Jammy Fishpaste’, leading him to sue the magazine for libel on three separate occasions. Robert Maxwell (called ‘Captain Bob’) famously sued Private Eye over allegations he had paid for a peerage, eventually winning £225,000. He would later be discovered to have conducted large-scale fraud with money from his businesses’ pension funds.

Countless times, the editors of Private Eye (Ingrams from its launch until 1986 and Ian Hislop ever since) have been hauled before the British libel courts or threatened with extremely costly litigation by expensive lawyers. And yet, the magazine has continued to challenge the established order and hold the powerful to account.

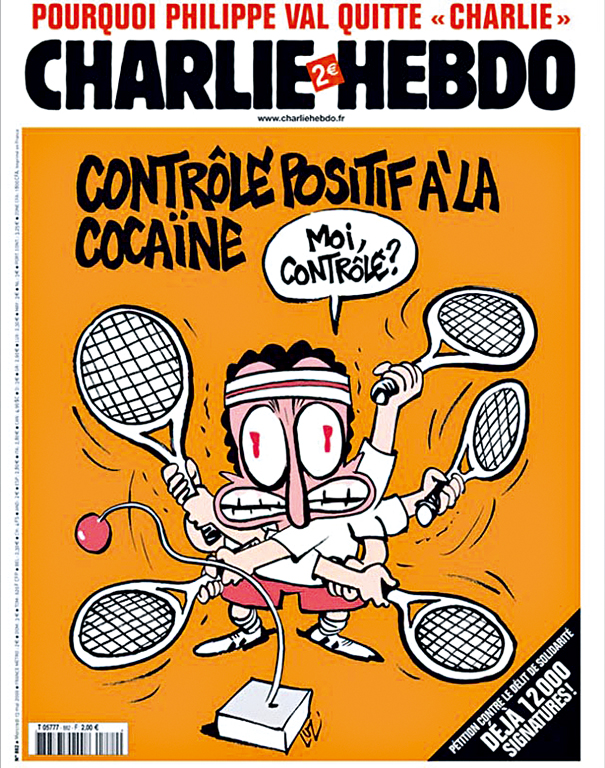

Charlie Hebdo

The magazine that has been in the news the most during the beginning of this year, for sadly tragic reasons, France’s Charlie Hebdo has been the scourge of the country’s political establishment ever since it was launched in Paris in 1970. It emerged after a previous magazine, Hara-Kiri, set up by humourist Georges Bernier and editor François Cavanna, was banned for mocking the death of former French President Charles de Gaulle in 1970.

Running initially for 11 years until 1981, Charlie Hebdo closed before being re-launched in 1992. It has courted controversy throughout its existence, mostly attacking the far right, and in particular the French nationalist National Front party, founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen and latterly run by his daughter Marine Le Pen. The magazine has also not pulled any punches in dealing with religion, with the Catholic Church, Judaism and Islam all coming under scrutiny from its cartoonists and writers.

Many of the magazine’s most notorious cartoons have riled sections of the Muslim community, with its depiction of the Prophet Muhammad carrying a bomb in 2007 causing the Grand Mosque of Paris to sue Chief Editor Philipe Val. However, in comparison to this one suit from a Muslim body, the magazine has been sued 13 times by Catholic organisations, mainly due to front covers mocking the Pope. In 2008, cartoonist Maurice Sinet published a cartoon in the magazine mockingly claiming Jean Sarkozy (son of then-President Nicolas Sarkozy) was going to convert to Judaism in order to marry Jessica Sebaoun-Darty, a Jewish heiress. The resulting furore led to Sinet being fired from Charlie Hebdo after he refused Val’s demand for an apology letter.

In 2011, the magazine’s offices were fire-bombed and its website hacked after it carried a cover with a picture of the Prophet Muhammad saying “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter!” In spite of further threats, the magazine continued to publish the image in subsequent issues. At the beginning of this year, that defiance was tragically met with an attack by two gunmen who murdered 12 members of staff. These included cartoonists Charb, Cab, Honoré, Tognous and Wolinski, economist Bernard Maris, and editors Elsa Cayat and Mustapha Ourrad.

The attack was condemned throughout French society, the Muslim community and the wider world. Large swathes of society came out in support of the magazine, including those who felt the initial cartoons were inflammatory and in poor taste. In the aftermath, Charlie Hebdo continued in its traditional vein by publishing another issue with the Prophet on the cover, this time with the slogan “Je Suis Charlie”. It achieved record sales of 2.2 million; somewhat more than the usual 60,000.

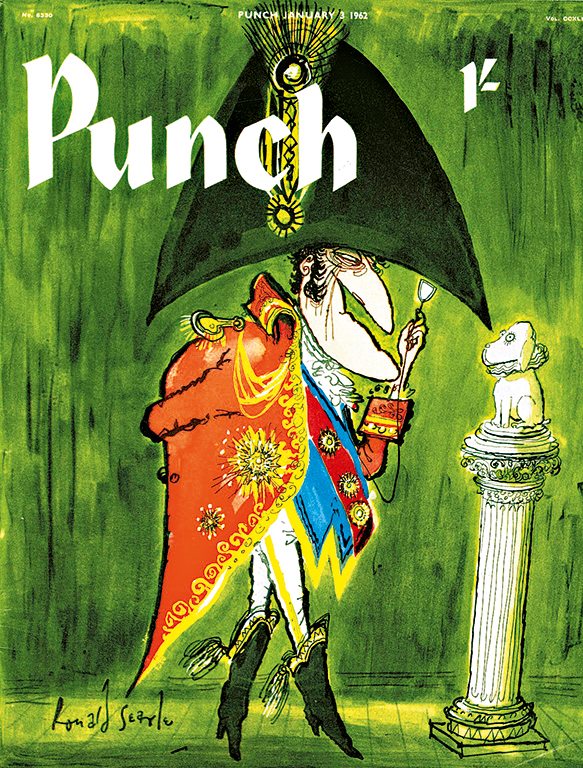

Punch

One of the oldest satirical publications in the world, Punch was founded at the height of the British Empire and at a time when the country dominated global affairs. Created by journalist, playwright and reformer Henry Mayhew and engraver Ebenezer Landells in 1841, it was also commonly known as The London Charivari, as a tribute to French satirical magazine Le Charivari.

The magazine pioneered the idea of cartoons as a humorous form of art. Its masthead included the glove puppet Mr Punch, from the Punch and Judy puppet show, symbolising its intent to cause havoc and poke fun at the world around it. Its cartoons would frequently mock the leading political figures of the day, particularly William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli during the 19th century.

Many of its cartoons were particularly scathing and had serious points, however. It frequently pointed out the high cost of maintaining the royal family, highlighting that Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert received an annual allowance of £30,000 at a time when the entire education budget was a third of that figure. Such was the influence of Punch, Winston Churchill himself cited the magazine as having taught him history while at school, describing it as “food for grown-up children” in his 1932 book Thoughts and Adventures.

Punch continued throughout the 20th century, satirising the bigger news stories of the day and branching out to target not only British figures. Key issues included sugar rationing during the First World War, and Hitler and Mussolini during the Second World War. Queen Victoria’s grandson and last German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II tried to get the magazine banned after it frequently belittled him and depicted him as a spoilt brat. He said that, during the First World War, the magazine had demoralised much of German society with its jibes.

The magazine also carried the work of some of the greatest writers of the day. Notable contributors included Winnie-the-Pooh author AA Milne, poet Sylvia Plath, humourist PG Wodehouse, novelist Kingsley Amis and poet John Betjeman.

Published weekly from 1841, Punch initially closed in 1992 before being re-launched in 1996 by Egyptian businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed, who some thought intended to use it to derail Private Eye, which often mocked him. It finally ceased publication in 2002, having left an unmatched legacy.

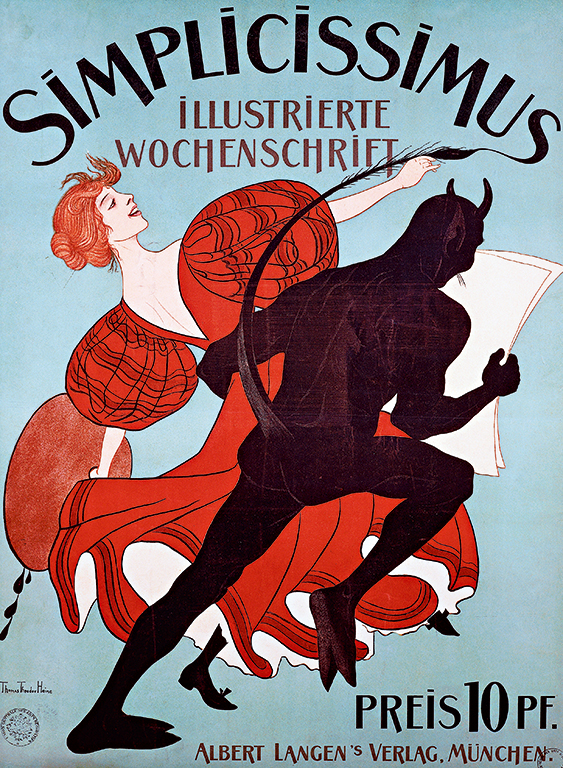

Simplicissimus

Despite the myth in the UK that Germans lack a sense of humour, the country has had a number of satirical publications. Perhaps the most influential of these was the weekly magazine Simplicissimus, which ran for the majority of the first half of the last century.

Launched by publisher Albert Langen in 1896, the magazine took its name from the 1668 novel Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch by German writer Hans von Grimmelshausen. The style of the magazine was modern for its time, and it featured political content that was considered particularly risky in Germany. In what was then a very traditional and conservative country, the magazine epitomised the more liberal and rebellious nature of Munich, the city in which it was published. Aiming particularly at the pompous and stiff Prussian army leadership, as well as German society’s rigid social class structure, the magazine carried a number of cartoons that derided the likes of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Among its contributors were novelist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Nobel Prize-winning poet Hermann Hesse, novelist Heinrich Mann, and acclaimed author of The Golem, Gustav Meyrink.

The apparently humourless Kaiser Wilhelm managed to get the magazine banned in 1898, after numerous issues that ridiculed him. While unsuccessful in doing the same to Punch, his efforts at home resulted in Simplicissimus’ founder Langen fleeing to Switzerland in exile and being fined 30,000 German marks. The magazine’s cartoonist, Thomas Theodor Heine, was jailed for six months, while writer Frank Wedekind was imprisoned for seven months. In 1906, the magazine saw its editor, Ludwig Thoma, imprisoned for six months for mocking the Church.

In the aftermath of the First World War and the years preceding the Second World War, Simplicissimus railed against extremist politics at both ends of the spectrum. The Nazi Party was particularly vociferous in its attacks on the magazine and issued a number of threats to the editors and artists. During the war, however, the magazine declined in popularity, and it ceased publication in 1944, following Jewish editor Heine’s resignation and exile. Briefly revived in 1954, the magazine finally closed in 1967.