IKEA opened its first store in Älmhult, Sweden, in 1958. It wasn’t until 1963, though, that the company debuted its iconic maze-like concept at a 31,000sq m warehouse in Stockholm. Inspired by the circular design of the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York City, which obliges visitors to follow a single winding path through the gallery, IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad decided he would set his own customers on a journey through a labyrinth of the retailer’s offerings. As a result, the Swedish firm soon became famous for its unique shopping experience – not to mention its Billy bookcases, electric blue tote bags and meatballs.

But today, IKEA faces a landscape of changing consumer habits: fewer people want to get in the car and drive to an IKEA warehouse, especially if they’re only picking up a lamp or a pair of curtains. Jesper Brodin, CEO of the retailer’s parent company, Ingka Group, is on a mission to modernise the firm with a drive to boost online sales and transform the in-store experience – all without losing sight of IKEA’s distinctive charm.

Building a digital brand

An IKEA veteran, Brodin succeeded Peter Agnefjäll as CEO of Ingka Group in September 2017. The business, which was formerly known as the IKEA Group, is the holding company for the main retail branch of IKEA and operates the vast majority of IKEA stores, as well as a number of Ingka Centres andthe group’s investment arm.

Brodin joined IKEA as a purchasing manager in Pakistan in 1995. Over the years, he worked his way up through various positions, including a stint as Kamprad’s assistant and numerous roles in product-range development, logistics and management. During Brodin’s more-than-two-decade tenure at IKEA, consumer habits changed radically, and competition in the retail industry has since become fierce.

IKEA is grappling with an omnichannel business model that blends its experiential, physical locations with the convenience and ease of online shopping

“Retail has been transforming for the past decade with the seismic shift from physical locations to online buying experiences,” Kerstin Braun, retail expert and president of trade finance provider Stenn International, told European CEO. But, as Braun noted, IKEA’s “unique customer experience” – its sprawling, labyrinthine stores – has been central to its growth. “People plan trips to their stores with both buying and leisure in mind, purchasing goods while also spending hours in store,” she said.

IKEA, like nearly every retailer today, is grappling with an omnichannel business model that blends its experiential, physical locations with the convenience and ease of online shopping. Its warehouse-format stores are also located far outside of town centres in order to help the company keep expenses – and, as a result, prices – low. According to Annabel Brown, a senior analyst at brand valuation and strategy consultancy Brand Finance, the cost of transitioning to a digital-first strategy “threatened the core goal of maintaining these low prices for consumers”.

This has all translated into slow progress in adopting a robust digital strategy. Although IKEA only began selling products online in 2009, Brown said the firm’s leadership is “fully aware that an omnichannel experience supported by e-commerce will be critical in the future, both to enable convenience and accessibility to a wider set of consumers, and to maintain IKEA’s reputation as an innovative global brand”.

Brodin inherited Agnefjäll’s digital transformation, and so far he has managed the overhaul successfully while driving further changes, including IKEA’s expansion of smaller-format shops in city centres. These ‘mini IKEAs’ offer customers a chance to test products in person and then, as Braun put it, make their decision “later at home with a glass of wine”.

IKEA CFO Juvencio Maeztu told Reuters in April 2019 that the company would be opening more of these mid-sized stores in the future, with locations earmarked in New York, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, Tokyo, Shanghai and Mumbai. “In the next 20 years, more people will live in cities… own fewer cars and share more,” Maeztu said. Braun believes rethinking the large suburban store model has been a critical development: “There is a growing population of households with only one person… For young people and single households, it’s not fun to drive a long way just to buy a few candles and a shelf.”

Tablets and chairs

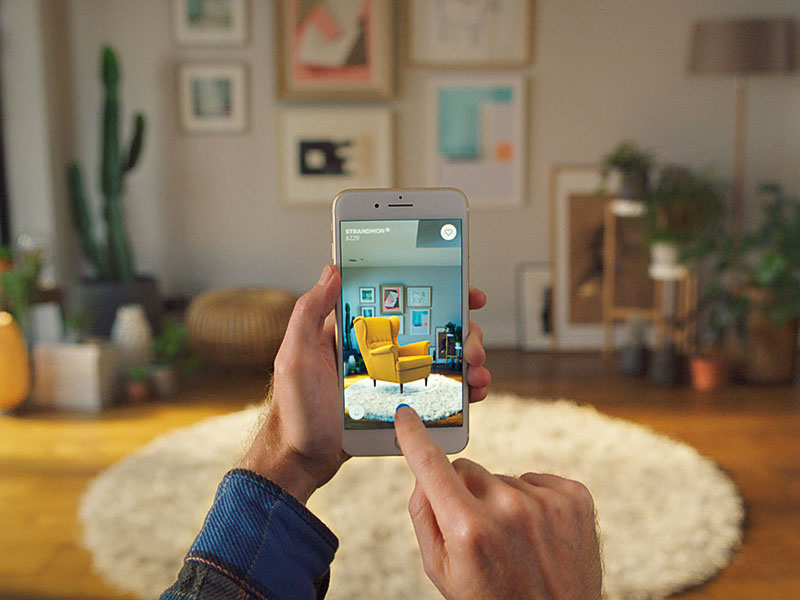

IKEA’s digital transformation is far from over. For example, the company broke ground in 2017 with the launch of its first augmented reality (AR) app, IKEA Place. Somewhat counterintuitively, though, the app wouldn’t allow customers to directly purchase the items they were visualising in their homes – instead, users had to go back to the website to make the purchase separately.

IKEA has since sought to rectify this issue: in an interview with Reuters in May 2019, IKEA Chief Digital Officer Barbara Martin Coppola said the firm’s new app, which is set to be rolled out across the company’s eight largest markets by the end of the year, will let customers shop remotely while using the AR tool.

Another problem IKEA has faced in recent years is its high delivery costs, which have quickly become outdated and off-putting to customers in an age of cheap and fast delivery. “The incongruence between AR innovation and outdated delivery fees signals to the state of transition IKEA is in,” Brown said. “IKEA is doing enough to keep up and, in some cases, lead the way for digital trends, but there is an air of compensation for previous complacency.”

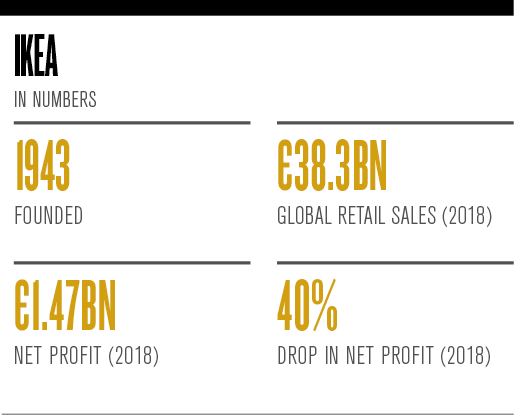

Yet Brown believes the cost of developing new digital resources should not be underestimated. In the 2017/18 financial year, IKEA’s net profit dropped 40 percent to €1.47bn. According to Maeztu, this was all “part of the plan” of avoiding rising prices. “It’s a conscious decision to lower the profit to finance the business transformation [and] we expect to keep the same level of profit for the next three years,” Maeztu told the Financial Times.

IKEA also announced in 2018 that it would cut 7,500 jobs worldwide to streamline the organisation. Brodin told Reuters that changes over the years had resulted in “a bit of duplicate work” in parts of the company, but added that the switch to e-commerce would create another 11,500 new jobs.

Boxing clever

As IKEA moves through its digital transformation, the company must also contend with an increasingly crowded marketplace. In 2017, IKEA’s share of the home furnishings market fell to two percent, down from 2.2 percent in 2014. The arrival of affordable, digital-first retailers such as Amazon and Wayfair has given consumers an easy option for online furniture shopping.

But even as its market share dwindled, IKEA’s global retail sales for the same period grew from €28.7bn to €38.3bn. “Growth in China and the US were significant drivers of this growth, despite the competition from e-commerce mammoths Amazon and Alibaba,” Brown said.

In European markets like France, however, the environment is very different. “With the gilets jaunes protests, the overall retail sector saw hampered growth [in France] in 2018,” Brown said. “However, e-commerce-only brands such as Made.com are expected to gain further ground, and it is the traditional, established brands such as IKEA [that] have struggled [to] remain relevant among wealthier consumers who demand unique, custom goods. Therefore, the key source of growth for IKEA must be in international markets.”

Indeed, Brodin has worked to stem the flow of market share loss by entering new territories, including opening the company’s first store in India in August 2018 – a moment that was around a decade in the making. According to a 2017 report by the Brookings Institution, India could surpass the US as the world’s second-largest middle-class market by 2022; IKEA plans to open 25 stores across the country by 2025.

While no major home furnishings brand currently dominates the Indian market, IKEA will face challenges in selling flat-pack furniture to a population with a much less established DIY culture. “Leading brands such as HomeTown and HomeStop still struggle to gain a bigger share of consumer spend, and there was a gap in the market for an affordably priced competitor,” Brown said. “Therefore, the entry of IKEA into India is both risky and exciting.”

Braun added that India’s first IKEA store would also attract younger customers, “particularly the young professionals who went abroad to study and returned home to the good job opportunities in their [home nation’s] growing economy”. Brodin told the Indian financial newspaper Mint that India would be a “test laboratory” for the further worldwide expansion of IKEA. The firm opened 19 new stores in the 2017/18 financial year, bringing its total to 422 stores in more than 50 markets.

Further expansions have been announced in North America (where IKEA plans to open its first store in Mexico in 2020), South America (where nine new stores are planned over the next decade across Chile, Peru and Colombia) and in Asia (where IKEA will open its first city-centre store in Tokyo and its largest ever store in the Philippines in 2020).

Ahead of the flat pack

With IKEA’s global presence growing, the company is also conscious of its environmental footprint. IKEA has already committed to ensuring that all of its products are made from renewable, recyclable or recycled materials, and that its operations are run by 100 percent renewable energy, by 2030. By 2020, the firm will have completely phased out single-use plastics.

Still, IKEA is the world’s largest consumer of wood: according to its website, the furniture maker consumes a whopping one percent of the global supply of lumber. IKEA has also faced criticism that its cheap, disposable furniture has supported a throwaway culture. To combat this, the company announced that it would trial a range of furniture-leasing offers in 30 of its markets by 2020.

Brown said the firm’s furniture rental plan “takes sustainability to the next frontier”, but in order to find any real success with the scheme, IKEA’s furniture will have to be of a high enough quality to survive multiple uses. “The success of this new venture will be determined by IKEA’s ability to meet the goals of designing sustainable, durable furniture within the key criteria of remaining cheap and accessible,” Brown said.

Brown said the firm’s furniture rental plan “takes sustainability to the next frontier”, but in order to find any real success with the scheme, IKEA’s furniture will have to be of a high enough quality to survive multiple uses. “The success of this new venture will be determined by IKEA’s ability to meet the goals of designing sustainable, durable furniture within the key criteria of remaining cheap and accessible,” Brown said.

Further, IKEA has started trialling a scheme that allows customers to take their used IKEA furniture back to the store in exchange for a voucher. IKEA will then refurbish and resell the products at a discounted price. In IKEA Australia’s People and Planet Positive 2018: Creating a Circular IKEA report, the company estimated that 13.5 million pieces of furniture could be recycled, reused or repaired in order to be given a second life.

The company is currently a hub of experimentation – Brodin told the Financial Times in 2018 that IKEA has “never had as many tests ongoing”. Brown added: “Brodin himself rejects the title of chief innovator or visionary, nor does he aspire to these accolades… Instead, the CEO accredits his ideas to his ability to listen, and to the entrepreneurship of his colleagues.”

According to Brown, Brodin devised the company’s transition plan, which includes moving IKEA further into city centres, exploring the opportunity of furniture leasing and boosting e-commerce sales, following a number of discussions with his colleagues. What’s more, Brown believes Brodin’s two-to-three-year timeline – compared with the traditional five-year plan – signals his “aptitude for change management”.

Despite this, Braun told European CEO that Brodin faces a tough road ahead: “We may see product and distribution innovations during his tenure, but no one has a crystal ball for what lies beyond online retail. This will be a difficult strategy to develop.”

Although he is only two years into his time as CEO, Brodin is deep in the midst of IKEA’s transformation. With many initiatives still in trial phases, it is difficult to gauge just how successful he has been so far. There is no doubt, however, that as Brodin has worked to build an IKEA for the future, his innovations have recaptured the industry’s imagination.