A corporate rebranding is a risky endeavour. If poorly calculated, even a simple name change or logo adjustment can result in public backlash, loss of consumer trust and unending bad press – not to mention the millions paid to marketing agencies for the privilege. Fortunately, when Danish Oil and Natural Gas – better known as Dong Energy – changed its name in November 2017 to reflect the company’s shift towards renewable energy, CEO Henrik Poulsen had already done most of the hard work.

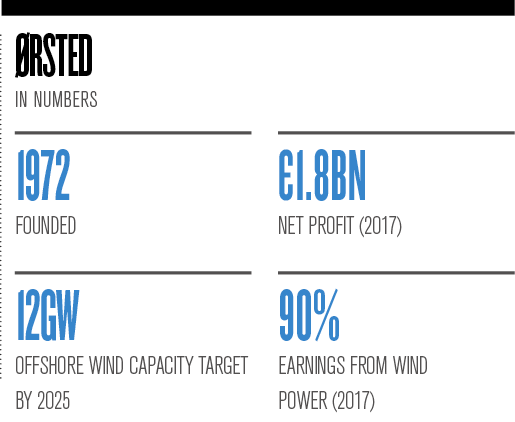

Poulsen agreed to sell all of the company’s oil and gas assets to UK petrochemicals firm Ineos for $1.05bn (€903.7m) in May 2017, having pledged to phase out coal-fired power generation by 2023 earlier in the year. Dong Energy already held the title of the world’s largest offshore wind producer, operating more than a quarter of the wind farms dotted throughout the planet’s oceans. The name change, it seems, was merely a formality.

Dong is now known as Ørsted, an ode to the 19th-century Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, who discovered electromagnetism and laid the foundations for modern electricity generation. And alongside the company’s new name and bright blue logo came a bold vision: a world that runs entirely on green energy.

Green gamble

Poulsen recognised Ørsted’s potential to be a leader in the renewable energy space from the day he joined the company in 2012. When he announced he would step down as CEO of Danish telecoms giant TDC to lead Dong Energy, Poulsen said the firm held “a key position in Denmark’s transition to green energy”.

As prices for renewable energy drop, companies are increasingly feeling the pressure to act on climate change

In the time since Poulsen’s declaration, Ørsted’s offshore wind capacity has grown from 1.7GW in 2012 to 3.9GW in 2017, with projects in Denmark, Sweden, the UK, Germany and elsewhere. More than DKK 80bn (€10.7bn) has been invested in the expansion so far and, by 2025, Ørsted is targeting an offshore capacity of between 11GW and 12GW.

But it would be misleading to suggest the company’s turn to renewables was all Poulsen’s doing. Ørsted, under one name or another, has long been invested in renewable energy. One of the company’s earliest iterations, Elkraft, was responsible for building the world’s first offshore wind farm in 1991 off the coast of Denmark. It’s under Poulsen, however, that the firm has made significant strides to hold its position as an industry leader.

“I think at the start of that process, [the shift away from oil and natural gas to offshore wind] could have been deemed as quite a bold move, and I think they’ve done that pretty well in that short time frame,” Gurpreet Gujral, an alternative energy and utilities analyst at Macquarie, told European CEO. “The offshore wind business, in my point of view, has been a huge success.”

According to industry body WindEurope, Ørsted was the largest owner of offshore wind power in Europe last year, with 17 percent of cumulative installations at the end of 2017 – a slight increase from 2016. Ørsted’s most impressive feat, however, has been its success in making renewable energy profitable: renewables now account for 83 percent of capital employed at Ørsted, up from 21 percent in 2006. At the same time, the company’s operating profit has more than doubled to DKK 22.5bn (€3bn). Furthermore, returns made on capital investments have more than quadrupled from six percent to 25 percent.

Jonathan Marshall, Head of Analysis at the UK-based Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, told European CEO the main change in the sector since Poulsen took the reins was a drop in costs, which he attributed to investor confidence and technological advancements: “As the industry has matured and become less risky to invest in, [investors are] demanding lower returns on their loans, which, for a [capital expenditure] heavy investment and [capital expenditure] heavy infrastructure, makes a big difference to the overall costs.” Subsidies have underpinned the offshore wind sector since it started in the 1990s, but Marshall believes the industry has grown to the point where it often doesn’t need government support.

This stark drop in prices was clearly demonstrated last year, when Ørsted was awarded a contract to build Hornsea Project Two off the coast of the UK. With a capacity of 1.4GW, the wind farm will be the world’s largest when it is completed in 2022. However, the price Ørsted paid for the contract for difference was 50 percent lower than it paid in the previous round just two years earlier.

As prices for renewable energy drop, companies are increasingly feeling the pressure to act on climate change. “If you go to an annual general meeting or watch a big presentation online, all of the questions from an audience to the CEO or the panel are about carbon emissions; about how these companies are going to deal with the problem,” Marshall said.

Meanwhile, just five or 10 years ago, questions from investors would more likely revolve around exploration licences and shareholder returns. Marshall continued: “There’s a sense that the industry has completely changed, and companies are having to respond to it.”

Hatchet man

The transformation of Ørsted over the past six years has been no small undertaking, but Poulsen is famously fond of a challenge. He was thrilled to join a company that would thrust him onto a bigger stage. Upon leaving TDC in 2012, Poulsen called his new role as CEO of Dong Energy an “uncommonly interesting challenge” and said one major attraction was the “challenge that comes with the fact that Dong Energy is a company of which many people have high expectations”.

Poulsen was referencing the fact that Dong’s finances had taken a hit in 2012. Operating profits had fallen by more than a third and the company’s credit rating had been slashed as a result. The state-owned firm was running low on capital to invest in its emerging offshore wind business.

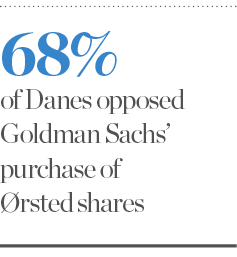

As part of a restructuring plan in 2014 – after the Danish Government had declined to inject new equity into the business – Dong sold almost 19 percent of the company to Goldman Sachs for DKK 8bn (€1.1bn). The controversy of the sale was so profound it nearly caused the government to collapse. Denmark’s ruling coalition split, with six cabinet ministers and the Socialist People’s Party withdrawing from government. A poll at the time showed 68 percent of Danes were against the sale to Goldman, while nearly 200,000 people signed an online petition opposing the deal.

Despite this hurdle, Poulsen went on to lead the company through a period of immense change, overseeing an initial public offering (IPO) in June 2016 that boosted its international profile considerably.

The successful float valued Ørsted at DKK 98.2bn (€13.2bn), one of the biggest stock market listings of that year and the biggest ever in Copenhagen. On the first day of trading, Ørsted’s shares soared by around 10 percent, proving there was a strong investor appetite for the fast-growing offshore wind industry.

“Ultimately, I would describe the IPO as a success,” Gujral said. “[Ørsted] performed very well as a listed business not only in terms of a stock price point of view, but an operational point of view. [It met its] guidance numbers, and more often than not [it has] actually had to raise [its] guidance numbers.”

Ørsted has not been Poulsen’s only success story. He faced similar challenges at TDC and, before that, at Danish toymaker LEGO. In a 2014 address to the students of Aarhus University, his alma mater, Poulsen said he had “without a doubt changed jobs more often than most people”, but admitted he enjoys joining a business just as it is looking to chart a new course: “The consistent theme in my career is probably the fact that I tend to move on when things settle down again.”

Poulsen was an instrumental part of LEGO’s turnaround but, once the company got back on its feet, he left. “The obvious choice would have been to stay and enjoy the upswing, given that I’d been there for the tough part of the journey,” Poulsen said. “But I’d spent seven years at LEGO, and I simply couldn’t find the energy to continue.”

Poulsen had never sought out the role of “hatchet man” – someone who carries out controversial or unpleasant tasks – but he has ended up in that position time and time again. An unnamed adviser for Ørsted’s IPO told the Financial Times Poulsen had a “quiet self-confidence”, adding: “He’s very bright, very well prepared, and ultimately he just really delivers.”

Greener pastures

Some imagined Ørsted’s IPO to be Poulsen’s final challenge at Denmark’s largest energy firm – his name has been mentioned in connection with the likes of Danish shipping giant Maersk and oil behemoth Royal Dutch Shell – but Poulsen has suggested he is not finished yet. At the time of the IPO, Poulsen told the Financial Times that his journey with Ørsted was “only getting started”.

Poulsen also told the students at Aarhus that he planned to stay with the energy firm for the long haul: “It might sound a bit ambiguous, but I’d like to make Dong Energy the company it has the potential to become, and this is more important to me than my desire to move on.”

And there is still plenty of work to be done at Ørsted. After the company beat its quarterly operating profit forecasts at the start of this year – thanks to a strong performance from its offshore wind business – Poulsen announced the firm would be expanding into other areas of renewable energy generation and storage, namely onshore wind and solar power. Poulsen said: “We have transformed the company into being an entirely green energy company and, therefore, we find it natural to now expand our portfolio of renewable technology.”

Although Ørsted was previously involved in onshore wind, it sold the business in 2013 due to financial challenges. “For an international business like Ørsted, I think there’s probably a lot of sense in looking to onshore [wind],” Marshall said.

However, Gujral was surprised by Poulsen’s decision to branch out into other forms of renewable energy. He speculated that Poulsen might have been looking to diversify the company’s assets: “I still don’t think that the onshore wind, solar and storage activity will be a similar size to the offshore business in any way. I think it will always be dominated by the offshore business.”

Ørsted is also facing more competition now than ever. Gujral explained that offshore wind development in Europe – where Ørsted was a pioneer – is becoming crowded. For the company to keep growing, it will have to look at other markets, namely the US and Taiwan.

“The challenge for Ørsted and [Poulsen] is to be able to replicate the success that they’ve had in Europe into these new markets,” Gujral said. “No doubt I think they’ll do well. I think they have an incredible franchise in this space with a lot of smart people that are dedicated offshore wind specialists, which is to their advantage. But it is not going to be like their time in Europe; it will be a more competitive process this time.”