Every now and again, a story is told that is so inspiring, captivating and full of hope that we are blindsided. There’s so much suffering in the world that when we are offered some kind of relief, we jump on board without a second thought. Add to this an incredible technological breakthrough – pioneered by a smart young woman, no less – and this inclination becomes all the more ardent. Such was the case with Elizabeth Holmes, former CEO of the now-infamous health technology company Theranos.

Just a few years ago, Holmes could be found gracing the covers of magazines. She was the rising star of Silicon Valley, set to revolutionise the US healthcare industry and save countless lives in the process. The company promised that, using a tiny vial of blood obtained from a pinprick to the fingertip, it could offer hundreds of blood diagnostic tests, considerably reducing the cost of phlebotomy and enabling customers to gain greater control of their health.

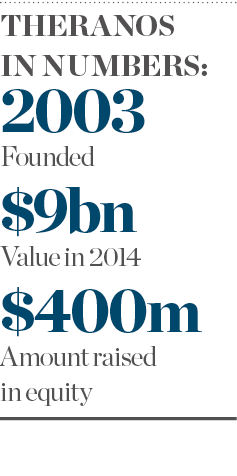

At its peak, Theranos was worth $9bn (€8.09bn) and had 500 employees. Its board was a who’s who of the investment world, while Holmes herself was lauded by the US’ political elite. Today, the company is worth nothing. At the end of June, it was revealed that Holmes is set to go on trial next summer and faces 20 years in prison for fraud and conspiracy, though she maintains her innocence. How quickly things collapse when they are built on a house of cards.

Promising start

To understand how Holmes managed to dupe so many people, it’s best to start at the beginning. Holmes was born in Washington DC to Noel, who worked as a foreign policy and defence aide, and Christian Holmes, who served as vice president of energy company Enron at the time of its scandalous downfall. Though Christian went on to work for various government agencies, the Holmes family struggled to come to terms with their lost position in the world. The family held a belief that their daughter would restore them to their rightful social status.

A culture of secrecy shrouded Theranos from the beginning, and for good reason – there was a great deal to hide

The family later moved to Houston, where Holmes excelled at a private school. She was a bright, studious child. A story Holmes often told was how she drew detailed illustrations for a time machine when she was just seven years old. According to Vanity Fair, she wrote a letter to her father two years later, which read: “What I really want out of life is to discover something new, something that mankind didn’t know was possible to do.”

At high school, Holmes was a straight-A student and even started a business selling software that translated computer code to schools in China. She also began lessons in Mandarin, which later enabled her to spend a summer interning at the Genome Institute of Singapore.

Holmes initially wanted to pursue a career in medicine, following in the footsteps of her great-great-grandfather, who was a surgeon and is the namesake of the Christian R Holmes Hospital. This plan was thwarted before it had even begun due to Holmes’ deep-set fear of needles. Instead, she studied chemical engineering at Stanford University.

Phyllis Gardner, a professor of medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine, described Holmes during her university days: “She was kind of naive, is the word I would say – young, not particularly outstanding in any way, kind of just normal looking and she had a normal voice.” In commenting on Holmes’ voice, Gardner is referring to the deep voice that Holmes later adopted, which many now say was part of her facade.

“She was brought to me by John Howard, who was the former president of Panasonic America… He was extremely impressed by her,” Gardner continued. “He said, ‘I have this brilliant young woman with this amazing idea’. Quite frankly, I found her to be anything but brilliant.”

Holmes’ idea was to use nanotechnology to create a skin patch that could detect infections and administer antibiotics. “I said to her, ‘This is difficult’,” Gardner said. “First of all, what infections would you detect? And what sample do you need? Do you need blood? You’re not going to get that from a skin patch unless you have needles in there.” She also advised Holmes that it was simply not possible to administer antibiotics through a skin patch: “Antibiotics are not that potent… That’s why you have an IV bag: because it takes a lot of material.”

In a bid to drum reality into her, Gardner introduced Holmes to other experts. But despite repeated warnings, she would not listen. Though Holmes eventually dropped the patch idea, this story says a great deal about her obstinacy and her refusal to take the advice of experts on board.

Gaining traction

Holmes turned to one of her teachers, Professor Channing Robertson, for guidance. Unlike Gardner, Robertson was enraptured. “I knew she was different,” Robertson told Roger Parloff in the cover story for Fortune magazine in 2014. “When I finally connected with what Elizabeth fundamentally is, I realised that I could have just as well been looking into the eyes of a Steve Jobs or a Bill Gates.”

With Robertson’s support, Holmes started her company, which she first called Real-Time Cures and later renamed Theranos – a portmanteau of therapy and diagnosis. Robertson became her mentor, at first serving as a voluntary director of the company before leaving academia to become a full-time employee in 2013.

In September 2003, Holmes filed a patent application for a “medical device for analyte monitoring and drug delivery”. It would be the first of many. The next year, aged 19, she dropped out of Stanford to work for Theranos full time. “I originally did not intend to drop out of Stanford, but I wasn’t going to any classes and I was spending all of my time talking to [venture capitalists] and so then, logistically, it just [seemed] like a waste of money,” Holmes said at a Stanford Technology Ventures Programme talk in 2009.

The doomed patch-based drug delivery proposition was finally put to bed, but next came the one for which Theranos became famous. Holmes was armed with a new outlandish idea – to carry out diagnostic tests using just a pinprick of blood – but she didn’t have the cash to start developing it. She approached Tim Draper, the father of her childhood best friend and a serial investor who has made billions of dollars investing in a vast range of projects. It was Draper who got the ball rolling on Theranos, giving Holmes her first million-dollar cheque. With him on board, other bigwig investors followed.

Elizabeth Holmes managed to pull the wool over (almost) everyone’s eyes: seasoned politicians, incredibly successful investors, the tech elite and the media

“Larry Ellison invested just because Tim Draper did,” Gardner told European CEO. “He didn’t do any due diligence or anything. It was what we call ‘friend and family investing’. And then, because it was Tim Draper and Larry Ellison, she got more fans and then it evolved – Rupert Murdoch got involved.”

The political elite soon followed, with former secretaries of state George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, and former secretary of defence Jim Mattis, joining Theranos’ esteemed board. Notably, medical experts and scientists were absent. “None of them, with [the] exception of possibly Senator William Frist, had any concept of what they were looking at,” Gardner said.

Bad blood

Theranos was based on the idea that, using proprietary technology, it could take just a pinprick of blood from a patient’s finger and use it to perform more than 200 diagnostic tests. The technology took the form of a sleek black box named the Edison. It could be used anywhere, from an operating theatre to the battlefield, Holmes often claimed. Within a few minutes, hundreds of blood analyses would take place, detecting antigens in the blood, hormone levels and even some cancers.

Holmes often explained how she was driven to develop the technology by her fear of needles. She wanted to replace the outdated mode of drawing blood, which she likened to torture. “The process of having these big tubes of blood drawn from the arm can be very painful and is something that is really scary for a lot of people,” she said in an interview with USA Today in 2014. “Our greatest motivation in doing this is… that testing begins to be more accessible for little kids or elderly persons or cancer patients or people who are just scared of having these big needles stuck in their arms and blood sucked out.

“Over the last 10 years, Theranos has worked to redevelop all of the tests run in a traditional laboratory to be able to take a tiny sample, a few droplets of blood, instead of the big tubes that are traditionally drawn from an arm. And we’ve made the tests from these few droplets of blood available at prices that are unprecedented.” According to Fortune, Theranos charged around half – sometimes even a quarter – of what independent labs did, while its prices were a tenth of hospital labs’ prices.

From the start, however, Holmes was unwaveringly secretive about how the Edison worked. She gave little away, using vague jargon to conceal the specifics. She told Fortune the technology would use “the same fundamental chemical methods” as other labs, “optimising the chemistry” and “leveraging software” to work with such small volumes.

In November 2013, Theranos announced a partnership with Walgreens, the second-biggest pharmacy chain in the US. Theranos Wellness Centres opened in 21 of Walgreens’ stores – one in Palo Alto, California, and the rest in Phoenix, Arizona. A press release at the time promised customers “less invasive and more affordable clinician-directed lab testing from a blood sample as small as a few drops – one-thousandth the size of a typical blood draw”.

The move marked a big step in Theranos’ mission to be within reach of every single American. The plan was to continue rolling out wellness centres across all 50 states. Safeway, meanwhile, spent around $350m (€315m) building clinics in more than 800 of its supermarkets to offer Theranos blood tests from. It’s worth noting that these tests never happened.

By 2014, the company had raised over $400m (€359m) in equity and was valued at $9bn (€8.09bn), with Holmes retaining more than 50 percent of the stock. All funding was given on the condition that Theranos did not have to reveal how the technology worked.

Exposing lies

This culture of secrecy shrouded Theranos from the beginning, and for good reason – there was a great deal to hide. But for Holmes, secrecy also acted as another way for her to emulate her enigmatic hero, Steve Jobs. She also started dressing like the late Apple CEO, always wearing black and donning his signature turtleneck. She poached designers from Apple to capture a similar aesthetic for the Edison and referred to the device as the “iPod of healthcare”. Holmes considered herself a female version of Jobs, and the same comparison was often made in the media.

But it wasn’t just outsiders who were denied details of how the Edison worked. Even those working for Theranos were given little information. Departments were purposefully siloed, with no team knowing the progress (or lack thereof) the others had made. This culture enabled Holmes and the company’s president, Ramesh ‘Sunny’ Balwani, to continue hiding the fact that the technology simply did not work.

Meanwhile, Holmes’ erratic behaviour worsened. “She was paranoid,” Gardner said. “She put bulletproof windows in her office, she had bodyguards, she had a personal jet.” According to an HBO documentary about the company, employees were tracked at all times, with Holmes’ assistants keeping tabs on when they arrived and left the office each day. Furthermore, the documentary explains, both Holmes and Balwani read all of their employees’ emails, even when they were not copied in.

When someone questioned Theranos’ technology or shared concerns, they were fired soon after

Often, when someone questioned the technology or shared concerns, they were fired soon after. Employees had to sign NDAs and were under strict instructions to never talk about the company with outsiders. Over the years, the company filed a number of lawsuits against its employees for breaking their NDAs, administered by one of the most prominent lawyers in the US – Theranos board member David Boies, no less.

Things finally began to unravel in 2015 thanks to one article and one reporter – John Carreyrou. The Wall Street Journal piece revealed that the Edison was only being used for 15 of the 240 tests Theranos advertised. Results, meanwhile, were highly inaccurate and unreliable: they were given to real patients with real health conditions, but the cover-up continued.

As for the many tests that couldn’t be done with the Edison, Theranos simply used standard machines made by the likes of industry-leader Siemens. To bypass the equipment’s requirements, which were not compatible with Theranos’ blood samples, employees were instructed to hack the machines and dilute samples. “Some of the potassium results at Theranos were so high that patients would have to be dead for the results to be correct,” Carreyrou wrote. Eventually, Theranos Wellness Centres reverted to the traditional method of drawing blood, much to the surprise of patients.

When regulators or investors came to visit Theranos’ offices, they were duped. “They locked the proprietary Edison machines and did not show them to the regulators,” Gardner said. “They did all these tests on standard machines and other commercially available devices.” Following Carreyrou’s article, Holmes denied all of the accusations. Gardner told European CEO: “She’s a pathological liar and she’s left a trail of destruction in people’s lives, including patients… and employees.”

Now, the lies have come to the fore. In 2018, both Holmes and Theranos were sued by the US Securities and Exchange Commission for “massive fraud”. By June of that year, Holmes was ousted as CEO of Theranos, while a grand jury indicted both Holmes and Balwani for having “engaged in a multimillion-dollar scheme to defraud investors, and a separate scheme to defraud doctors and patients”. Their trial is set for August 2020, with both of the accused pleading not guilty to the charges.

Holmes managed to pull the wool over (almost) everyone’s eyes: seasoned politicians, incredibly successful investors, the tech elite and the media. Her audacious capacity to lie was almost unfathomable. Perhaps she was motivated by a desire to help people but, when looking at Holmes’ history, it seems her grandiose self-image and ambition to become a legend drove her above all else. If she had taken the advice of others on board and created a less toxic, more fruitful environment at Theranos, perhaps Holmes could have come closer to achieving her goals. Instead, she created a legacy of an entirely different kind.